Stay With Me

I started this project as a graduate thesis photo story. I wanted to take a look at the lives, hopes, dreams and fears of families who have a relative in a Persistent Vegetative State. It is still debated worldwide on whether to make a family linger in hope of their relative coming back from a PVS, or to pull the cord on the life sustaining devices and let the patient die. I started this project not with the outlook to challenge the morale of those views, but to rather look at the daily struggle these families go through.

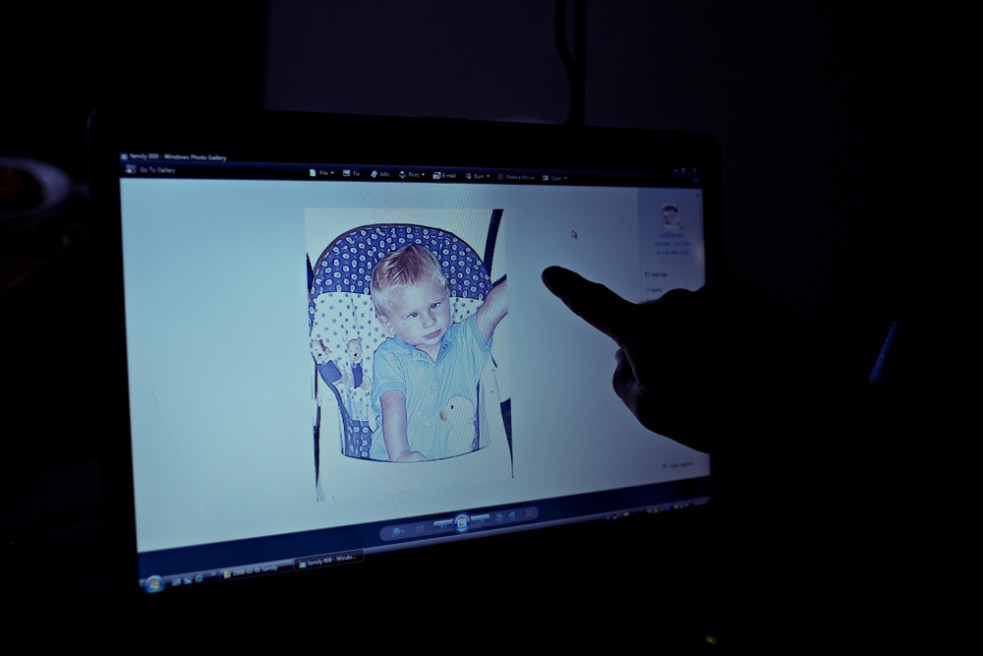

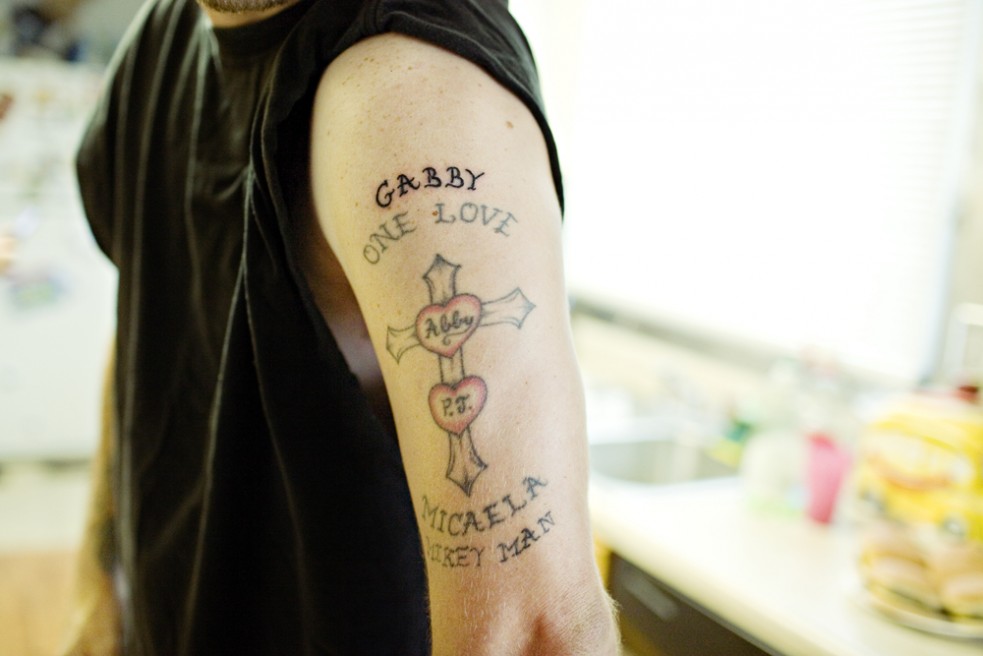

I went to South Africa to see Louis Viljoen, a man who came out from his PVS after taking a sleeping pill. After meeting him I saw three other families who each had a relative in a PVS. I noticed that severe brain injury causes great family strain in all levels (psychological, emotional, economical, social) The relatives of these patients have often lost friends, family members and are often in critical need for economical, psychological and emotional support.

I decided to continue the project worldwide to see how families across the globe cope with the situation they face when it comes to brain injury. So far the project has seen families in the US, UK and South Africa. Their experiences differ depending on their background. However, they all struggle toward the same objective, a sustainable life without abandoning their beloved ones.

I see in them much of what I learned all these years growing up with an elderly father, who passed away this year at the age of 99. The constant care, the endless love, and the modus operandi of taking a day at a time mirror much of my life with my father.

In the two years I have worked in this project I sadly found that there is no real interest in learning from the experiences of these families. There is a wide lack of interest from media outlets to share this project. Every week I receive emails from different medical staff that organize mailing lists, blogs, publish news on psychological support forums on varied themes. I see that the stories of these families could help so many, especially those who are recently presented with the realities of life affected by brain injury. In the multimedia pieces I have made on the families I documented, one can learn that life, immersed in the realities of brain injury, can continue fluently. At a different pace, life with brain injury can be often a positive and enlightening experience. Through tragedy, one's approach and vision of life change.

Not all families worldwide can relate, however, to the experiences of those families I have documented. In Santa Cruz, Bolivia, a care home dedicated to the care of more than 130 patients (with varied levels of brain injury and other neuro-disabilities) struggles daily to carry on. Brother Roa, a priest who is in charge of the home, tells me that the home only has space for 80 patients (expanded from the original capacity of less than 50) It is, sadly, a common practice for relatives that once they learn that their relative acquired a brain injury (because of an accident, or at birth, or drugs abuse) they decide to abandon them at the doors of the care home - some 60km north of Santa Cruz.

Brother Roa struggles to give his 'children', as he calls them, a 'family environment. But with so many of them and so few volunteers, how can I?' He weeps quietly after seeing the work I have done so far. He says that the patients in my photographs are lucky. Their families are still with them. I tell him I will go back.

The Fotovisura Grant will not only allow me to go back and work on a photographic documentary on the Teresa de los Andes care home, but will also allow me to spend more time and shoot a full length video documentary. I hope this way I will increase the chances of reaching a wider audience and share the worldwide issue of brain injury.