This account starts on March 16 in the valley of Cuzco, Peru. Upon arrival, the small city was dry and exhausting with a piercing sun over arid mountains. At first glance the streets were quiet and restrained except for a thick dust that blew in, covering everything at once"Š—"Šmoments later the dust would reced, leaving things just as they were. On March 17th I began looking for signs of Cuzco’s legacy; before its conquest by the Spanish, Cuzco was home to the Incas. Here the condor and the bull were wrestling for identity.

The Quechua have a storied and profound history. They also brought the world the potato, the llama and the condor. Their language is based on three vowels, relies on a dizzying amount of suffixes, and is widely used throughout Andean South America with over forty significant dialects.

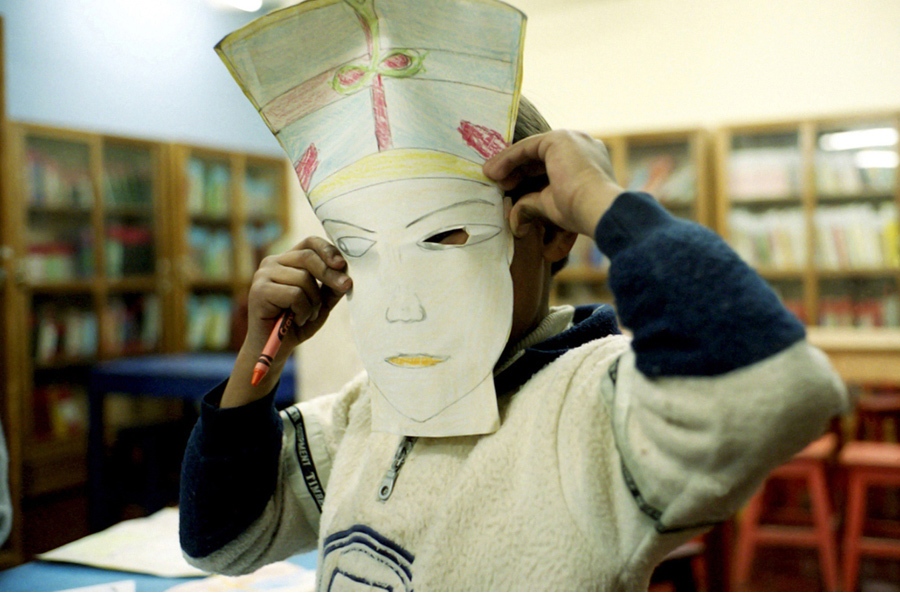

Each day from March 18 to 27 was divided between walking the old city and teaching English at the Qusqu Maki Children’s Center. Here the majority of children were from surrounding agricultural communities. Many were seeking to use English as a way to start a new career; yet this made me look towards that which they were outgrowing.

On March 27 my wife Adriana Teresa met a Quechua Jeweler named Romulo at one of the many markets. His craft was a family tradition passed down to him through five generations of artisans. We sat in his studio behind the market as he took the time to talk with us. He spoke of the increasingly Western outlook fostered in schools and of his culture’s resistance to adopting Spanish as an official language. This challenge has been confronted by each generation since the mid-1500s when Francisco Pizarro, with a few hundred Spaniards, divided and conquered an Inca nation of over a million strong.

Read the full story on Visura Magazine