Visura: Rashod Taylor on Documenting the Intimate Realities of Family, Legacy, and the Lens

Rashod Taylor is a portrait and fine art photographer who focuses on family, culture, legacy, and the Black American experience. Based in Springfield, Missouri, Taylor explores the intricate relationship between the past and the present through the medium and large format processes.

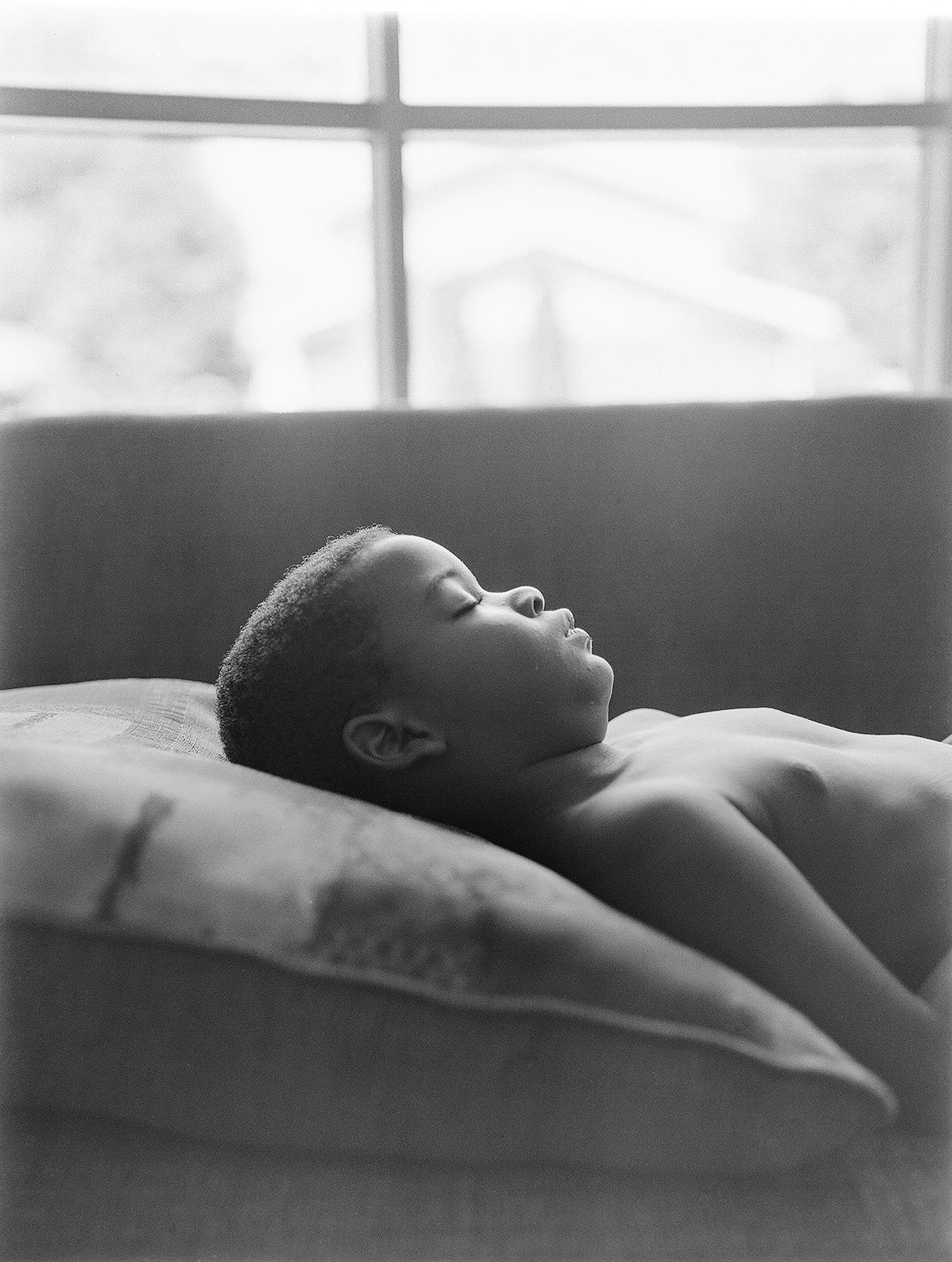

Taylor's ongoing personal project, "Little Black Boy," intimately documents his son's life and his journey through fatherhood. Throughout this project, Taylor explores the anxiety and realities of growing up black in America. In 2021, Taylor was the recipient of the Arnold Newman Prize For New Directions in Photographic Portraiture.

Taylor has collaborated with editorial clients such as National Geographic, The Atlantic, Essence Magazine, and Buzzfeed News. His work has been featured in CNN, The New Yorker, The Guardian, Forbes, Hulu, Feature Shoot, and Lenscratch.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Taylor's ongoing personal project, "Little Black Boy," intimately documents his son's life and his journey through fatherhood. Throughout this project, Taylor explores the anxiety and realities of growing up black in America. In 2021, Taylor was the recipient of the Arnold Newman Prize For New Directions in Photographic Portraiture.

Taylor has collaborated with editorial clients such as National Geographic, The Atlantic, Essence Magazine, and Buzzfeed News. His work has been featured in CNN, The New Yorker, The Guardian, Forbes, Hulu, Feature Shoot, and Lenscratch.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

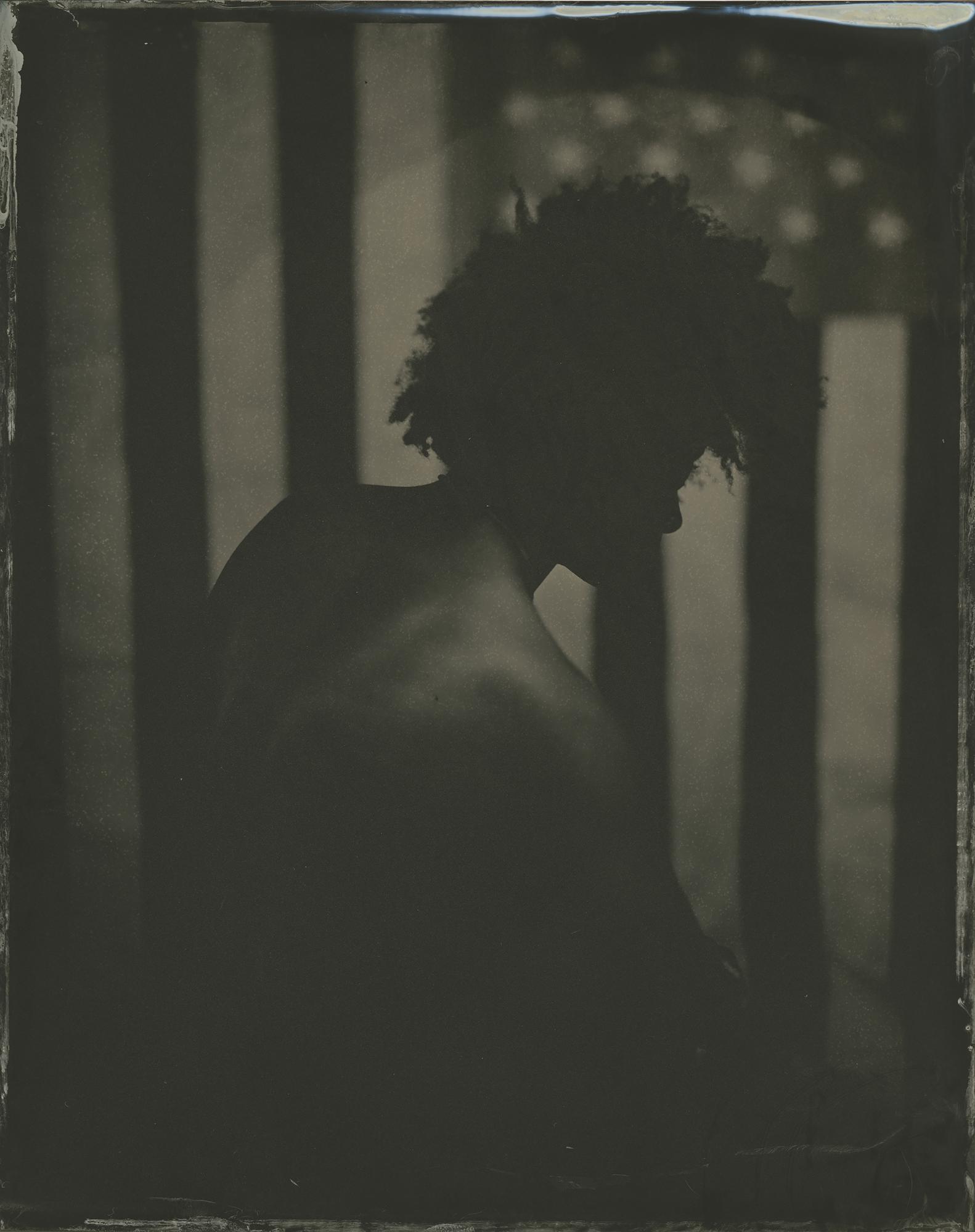

November 19, 2020 Staff Sergeant Vanessa Lewis Williams for the Georgia Army National Guard sits under a tree for a tintype portrait at the Georgia Army National Guard Readiness Center in Macon, GA. She is part of the 48th bergaide as a mechanic. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

What or who inspires and informs your approach to storytelling?

Rashod Taylor: I would say photographers for sure, but then also history.

I am interested in understanding where we came from, how that informs our present, and how our present is the springboard to our future. Understanding how systems and institutions were born because that informs me of why they are the way they are today. Specifically, with the black family historically, I did not see a ton of that documented. I am also interested in the civil rights movement and even as far back as the Civil War, which you can see more of in my work, My America.

Photographers that have informed the project Little Black Boy include Sally Mann because she photographed her family for years and I think that is kind of the bedrock when you look at family photography from a fine art perspective. Also the work of Richard Avedon. Even though he shot mostly in the studio, it is the interaction [he had] with the sitters. I am also inspired by the work of Dawoud Bey, who photographed a lot of black communities, and Deana Lawson, who photographs people of color all over the world. Her work is beautiful and vulnerable.

---------------

Rashod Taylor: I would say photographers for sure, but then also history.

I am interested in understanding where we came from, how that informs our present, and how our present is the springboard to our future. Understanding how systems and institutions were born because that informs me of why they are the way they are today. Specifically, with the black family historically, I did not see a ton of that documented. I am also interested in the civil rights movement and even as far back as the Civil War, which you can see more of in my work, My America.

Photographers that have informed the project Little Black Boy include Sally Mann because she photographed her family for years and I think that is kind of the bedrock when you look at family photography from a fine art perspective. Also the work of Richard Avedon. Even though he shot mostly in the studio, it is the interaction [he had] with the sitters. I am also inspired by the work of Dawoud Bey, who photographed a lot of black communities, and Deana Lawson, who photographs people of color all over the world. Her work is beautiful and vulnerable.

---------------

You could have picked any camera, why large format?

It felt right to move into that larger format because it allows the process to be more formal and slow down to compose. A large format provides the opportunity to take more time and really understand the elements that I want in the image: what works and what doesn't. I feel like having that bigger viewfinder also helps me visually and to be able to see everything.

I also like the look that the depth of field in large format provides, more so than in smaller formats. I think it adds a more three-dimensional aspect to the images.

---------------

It felt right to move into that larger format because it allows the process to be more formal and slow down to compose. A large format provides the opportunity to take more time and really understand the elements that I want in the image: what works and what doesn't. I feel like having that bigger viewfinder also helps me visually and to be able to see everything.

I also like the look that the depth of field in large format provides, more so than in smaller formats. I think it adds a more three-dimensional aspect to the images.

---------------

In your project "My America," you choose to work with the wet plate collodion process. How does this process contribute to your storytelling approach?

I chose the process because I feel like the past informs the present. I wanted to use the process to go back to the beginning - not the full beginning of slavery or anything like that - but I wanted to encapsulate that 1860s time period when wet plate became popular and where we were as Americans and as America that time.

I wanted to use that as a benchmark to where we were and then, moving forward, how the thoughts and ideas that people had back then are still prevalent today. They are prevalent through institutions and people; racism is still tightly woven into our American society. I wanted to link those two things from the past to the present. So the wet plate collodion process helped. I thought of that as a conduit to bridge that gap.

---------------

I chose the process because I feel like the past informs the present. I wanted to use the process to go back to the beginning - not the full beginning of slavery or anything like that - but I wanted to encapsulate that 1860s time period when wet plate became popular and where we were as Americans and as America that time.

I wanted to use that as a benchmark to where we were and then, moving forward, how the thoughts and ideas that people had back then are still prevalent today. They are prevalent through institutions and people; racism is still tightly woven into our American society. I wanted to link those two things from the past to the present. So the wet plate collodion process helped. I thought of that as a conduit to bridge that gap.

---------------

The Past, Year 2019, size 8x10, medium unique tintype. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

Why is it important to consider the tools we utilize in the storytelling process?

A couple of different reasons. I think you always think about the output. What is the final product that people will see? What is the product that I want to put out there, whether that's digital or whether that's shooting film? In most cases now there is always an output that is going to be on a computer screen. For me, I wanted to get back to holding something in my hand and making an original art piece.

When I think about longevity, I have tons of digital files just like everyone else, but I wanted to get back to having that tangible piece of work. And the longevity of it. I think digital files are always going to be around, but I know that these plates are gonna last at least 100 years because the plates that are made beforehand have lasted that long.

I think of it more like a gift, as an heirloom. For me, that process adds more significance to making an original piece that can't be replicated. It holds that depth when I am with the work.

---------------

A couple of different reasons. I think you always think about the output. What is the final product that people will see? What is the product that I want to put out there, whether that's digital or whether that's shooting film? In most cases now there is always an output that is going to be on a computer screen. For me, I wanted to get back to holding something in my hand and making an original art piece.

When I think about longevity, I have tons of digital files just like everyone else, but I wanted to get back to having that tangible piece of work. And the longevity of it. I think digital files are always going to be around, but I know that these plates are gonna last at least 100 years because the plates that are made beforehand have lasted that long.

I think of it more like a gift, as an heirloom. For me, that process adds more significance to making an original piece that can't be replicated. It holds that depth when I am with the work.

---------------

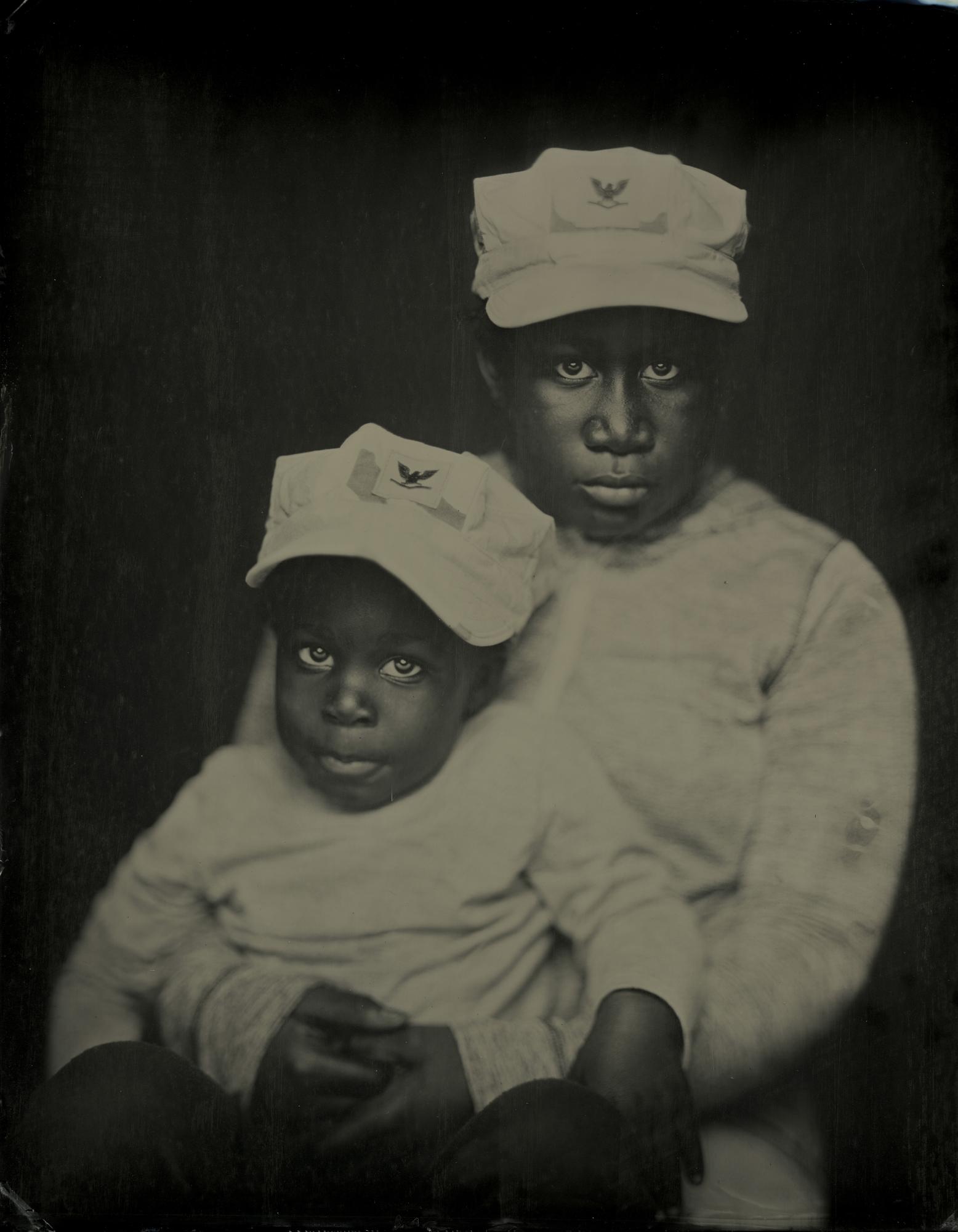

November 21, 2020 pictured from left to right Eric B. Kelsey jr. and his sister Ania N. Kelsey sit for a tintype portrait with their father's military hats at the home of their grandparents Ernest and Modester Lewis. Their father Navy Combat Veteran Eric B. Kelsey comes from a military family as his father Retired Army Combat Veteran Thomas Kelsey jr. and brother Navy Combat Veteran Thomas Kelsey III all served. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

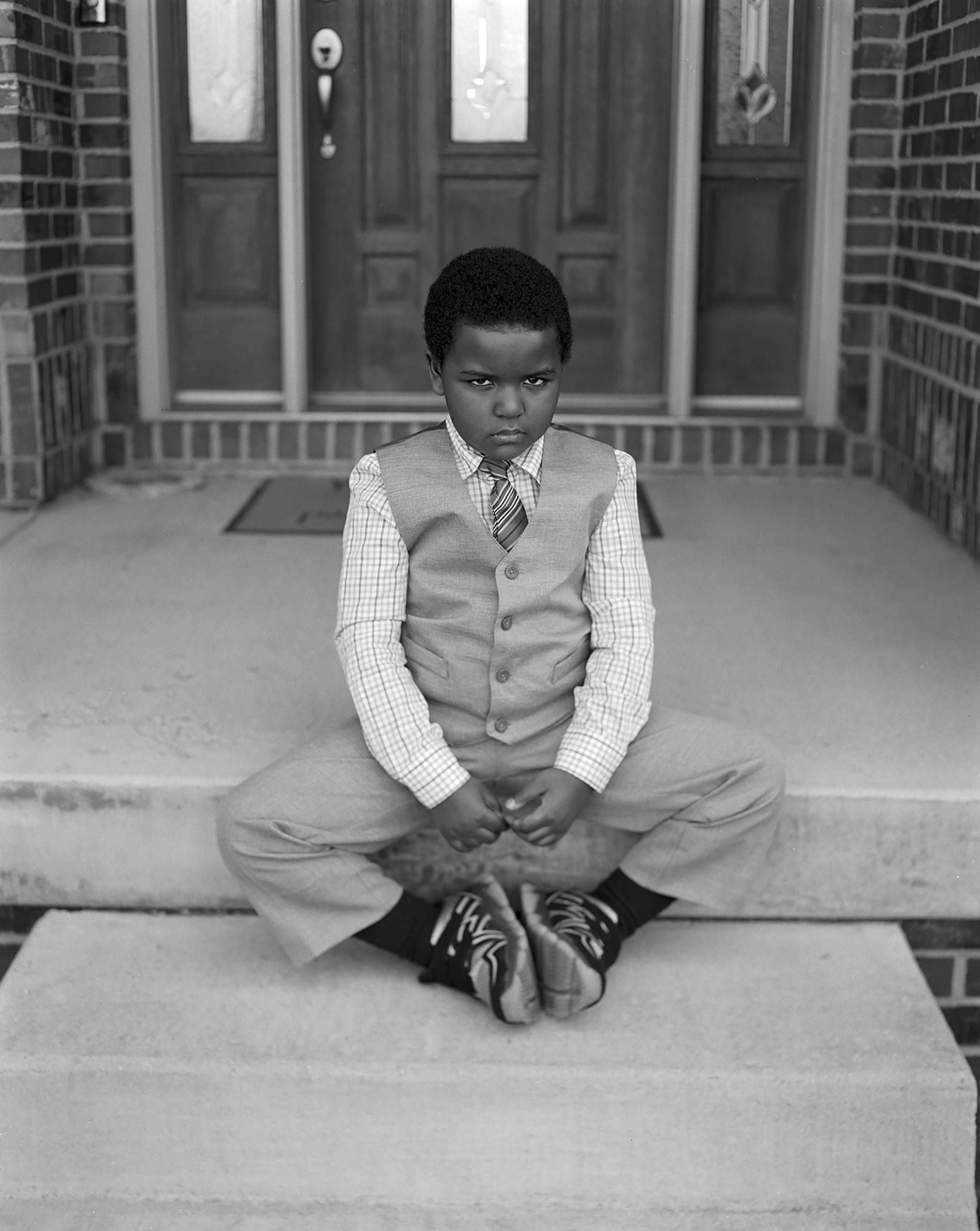

Can one portrait be a story?

I think one portrait can be a story. A picture that comes to my head is called “Easter Sunday.” It is a picture of my son sitting on the front stoop of the house super upset. He is in a tie. He has his vest on and nice pants, then, of course, he has tennis shoes on.

For me, that tells a story of my childhood because I remember my parents forcing us to dress up for Easter and take pictures. We just wanted to get the Easter eggs and candy, right? It takes me back to that time. For him, it was the same kind of thing. And I think that a lot of people identify with that image in terms of his facial expression and how set he is.

It tells a story not only about his story and about Easter in our family, but I think it tells other people’s stories because they can identify with it. They can think back to their own story and say, “Oh, wow, yeah, I remember when my mom made us dress up like this.”

One image can both tell a specific story in that context and who's in it, as well as help the viewer see another story – potentially one that is either in their own life, or a relative's life, or whoever. It can be two stories, essentially.

---------------

I think one portrait can be a story. A picture that comes to my head is called “Easter Sunday.” It is a picture of my son sitting on the front stoop of the house super upset. He is in a tie. He has his vest on and nice pants, then, of course, he has tennis shoes on.

For me, that tells a story of my childhood because I remember my parents forcing us to dress up for Easter and take pictures. We just wanted to get the Easter eggs and candy, right? It takes me back to that time. For him, it was the same kind of thing. And I think that a lot of people identify with that image in terms of his facial expression and how set he is.

It tells a story not only about his story and about Easter in our family, but I think it tells other people’s stories because they can identify with it. They can think back to their own story and say, “Oh, wow, yeah, I remember when my mom made us dress up like this.”

One image can both tell a specific story in that context and who's in it, as well as help the viewer see another story – potentially one that is either in their own life, or a relative's life, or whoever. It can be two stories, essentially.

---------------

Easter Sunday, 2021, 20x24 inches, silver gelatin print. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

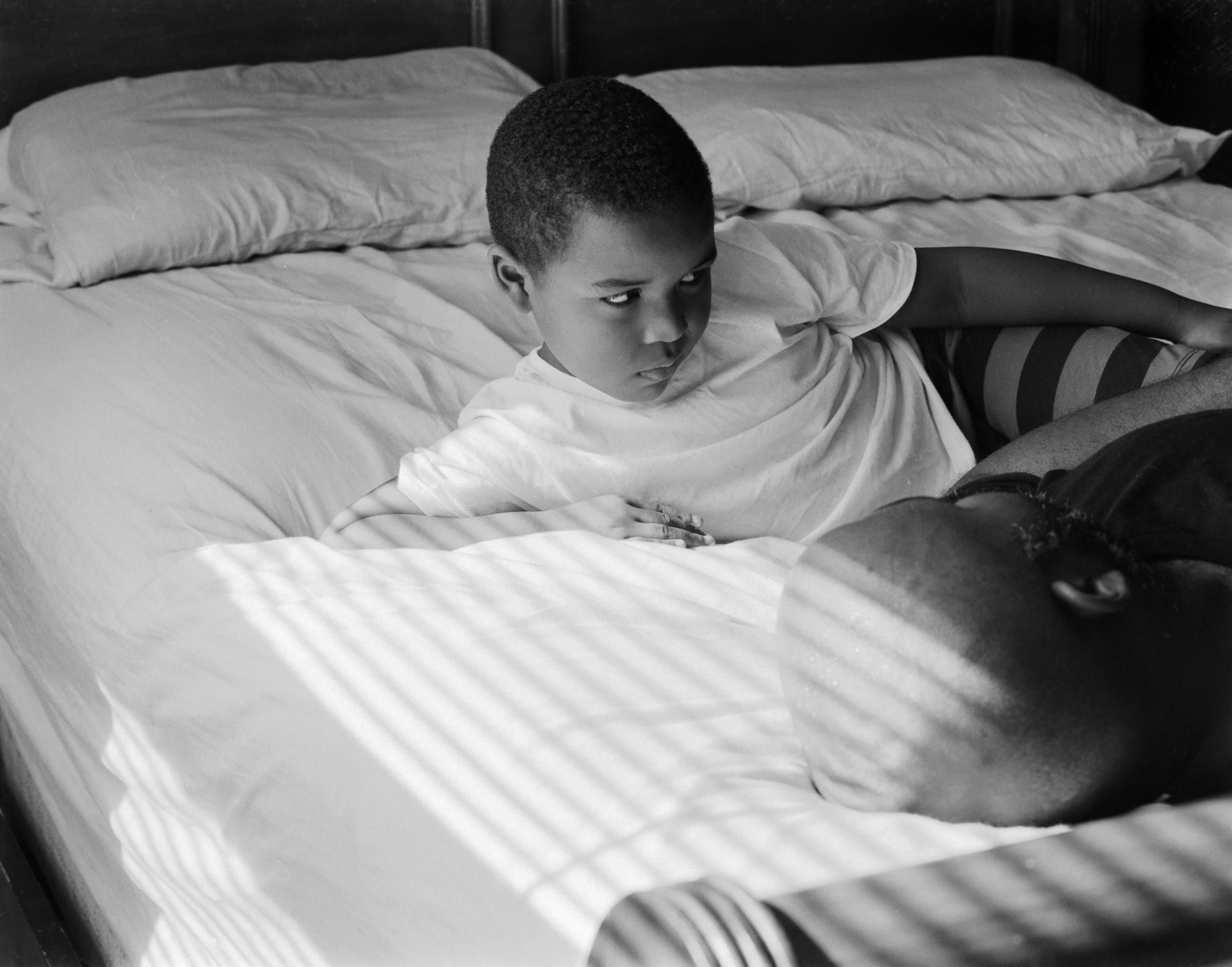

What motivated your decision to turn the camera on yourself in your long-term project, "Little Black Boy?"

I felt like, even though the story is really about him, it is partly about me too. I wanted to show the interaction between father and son.

I feel like the images that I'm not in, I still have a presence there because I'm the photographer. When you look at the whole process of making the image, I'm there, even though I'm not. I like that.

I also wanted the viewer to physically see that the father is there. Historically, when you look at fatherhood and especially black fathers, there is this idea that the black man was not there. I really wanted to go against that stereotype, because I do get to spend a lot of time with my son. I'm fortunate and blessed to have that ability in my life. And I want people to see that.

For me, it was not only being present, but then I also wanted to show that tenderness, that relationship with father and son on camera. And I think that is beautiful. It is powerful for me.

I felt like it was really important for me to have a presence in the images, not all of them, but in some of them.

---------------

I felt like, even though the story is really about him, it is partly about me too. I wanted to show the interaction between father and son.

I feel like the images that I'm not in, I still have a presence there because I'm the photographer. When you look at the whole process of making the image, I'm there, even though I'm not. I like that.

I also wanted the viewer to physically see that the father is there. Historically, when you look at fatherhood and especially black fathers, there is this idea that the black man was not there. I really wanted to go against that stereotype, because I do get to spend a lot of time with my son. I'm fortunate and blessed to have that ability in my life. And I want people to see that.

For me, it was not only being present, but then I also wanted to show that tenderness, that relationship with father and son on camera. And I think that is beautiful. It is powerful for me.

I think about those moments. I think about the time I spend with my son. I think about how he's growing up and how I'm here to help guide him through this thing called childhood.

I felt like it was really important for me to have a presence in the images, not all of them, but in some of them.

---------------

LJ Laying on The Bed, 2020, 20x24, silver gelatin print. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

What do you hope that your son will take away from seeing this body of work one day?

The grew up in a loving household, his parents loved him no matter what, and he had a good childhood and got to explore. I think the other part of it is maybe understanding that every little black boy may not have the same upbringing and that while he is different, he is still the same.

Also, that this was important work that we got to do together. I hope that he looks at it later in life and appreciates it or likes it and doesn't hate me for it. On a personal level that he understands the intent of the project. That it came from a good place, and that it came from a place of love, and that we had a story to tell.

---------------

The grew up in a loving household, his parents loved him no matter what, and he had a good childhood and got to explore. I think the other part of it is maybe understanding that every little black boy may not have the same upbringing and that while he is different, he is still the same.

Also, that this was important work that we got to do together. I hope that he looks at it later in life and appreciates it or likes it and doesn't hate me for it. On a personal level that he understands the intent of the project. That it came from a good place, and that it came from a place of love, and that we had a story to tell.

---------------

Halloween, 2022, 20x24, silver gelatin print. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

Can you tell me something about your project, "Little Black Boy" that you have not shared already and that makes it so important for you to continue?

For me to incorporate more joy and happiness. In the images, when you look at them, we know that there is love in the house, there is tenderness, and there is care, but at the same time, you indirectly see that with him.

I am interested in moving in a direction where at least some of the images show more facial expressions of happiness or joy. I think that's important to see too. Because a lot of the images are melancholy type, which is fine. I'm trying to tell a story over a certain period of time. So you're gonna have different things that happen that kind of bring it together. So if you think of a story, you think of a beginning, middle, and end. When you think of someone's life, you think of childhood you think of lots of highs and lows, including excitement and happiness.

At the same time, as he gets older, it will turn into something of its own. He is going to be more mature, he is going to be more cognizant of his surroundings and what he is doing. And I have been actually doing more self-portraits of him. I set up the camera and frame it, and then I will allow him to actually make the picture and hit the shutter. That is the newer work I have been making. That actually will be displayed in August in a solo show at the McLean County Art Center.

---------------

For me to incorporate more joy and happiness. In the images, when you look at them, we know that there is love in the house, there is tenderness, and there is care, but at the same time, you indirectly see that with him.

I am interested in moving in a direction where at least some of the images show more facial expressions of happiness or joy. I think that's important to see too. Because a lot of the images are melancholy type, which is fine. I'm trying to tell a story over a certain period of time. So you're gonna have different things that happen that kind of bring it together. So if you think of a story, you think of a beginning, middle, and end. When you think of someone's life, you think of childhood you think of lots of highs and lows, including excitement and happiness.

At the same time, as he gets older, it will turn into something of its own. He is going to be more mature, he is going to be more cognizant of his surroundings and what he is doing. And I have been actually doing more self-portraits of him. I set up the camera and frame it, and then I will allow him to actually make the picture and hit the shutter. That is the newer work I have been making. That actually will be displayed in August in a solo show at the McLean County Art Center.

---------------

As you expand and develop this series further, what impact do you envision this project having?

Rashod Taylor: I think the simple fact of people getting a new perspective of the Black American family structure or what little black boys go through.

I don't have to necessarily change anyone's mind on anything. It is just people being open to looking at work that has meaning and shows my perspective, maybe a different perspective that they haven't considered before.

---------------

Rashod Taylor: I think the simple fact of people getting a new perspective of the Black American family structure or what little black boys go through.

I don't have to necessarily change anyone's mind on anything. It is just people being open to looking at work that has meaning and shows my perspective, maybe a different perspective that they haven't considered before.

---------------

Drowning, 2021, 20x24, silver gelatin print. Photo by Rashod Taylor.

What are you reading or listening to right now that is influencing how you are thinking about your work at this moment?

The book I am reading right now is called The Digital Mindset by Paul Leonardi and Tsedal Neeley, which has nothing to do with art, but it's really interesting. That helps me to stay relevant and what it takes to thrive in the age of data algorithms and AI. As a photographer, it's so relevant.

I also just finished reading a book that I would encourage everybody to read at least once called, Making It In The Art World: Strategies for Exhibitions and Funding by Brainard Carey. You don't necessarily have to be an artist. Even if you are a photojournalist, it's still a good read. It talks more about why you make art, than really putting a plan in place. I'm going through the workbook right now. It's been very helpful.

This year, I also read a book called Something Personal by Norma Stevens. It goes through Richard Avedon's life. So that was just really interesting to me to hear some of the antidotes and behind-the-scenes.

Going back to history, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an autobiography. It is pretty short, so I read it a couple of times. It really was impactful for me to learn more details about his life: how he got out of slavery, how educated he was, and specifically, his mindset around photography. He was the most photographed person in the 19th century. And the reason he wanted to be photographed was because he wanted people to understand what a Black person who's educated and powerful and strong looks like. Because he knew how powerful photography and the power of images were.

---------------

The book I am reading right now is called The Digital Mindset by Paul Leonardi and Tsedal Neeley, which has nothing to do with art, but it's really interesting. That helps me to stay relevant and what it takes to thrive in the age of data algorithms and AI. As a photographer, it's so relevant.

I also just finished reading a book that I would encourage everybody to read at least once called, Making It In The Art World: Strategies for Exhibitions and Funding by Brainard Carey. You don't necessarily have to be an artist. Even if you are a photojournalist, it's still a good read. It talks more about why you make art, than really putting a plan in place. I'm going through the workbook right now. It's been very helpful.

This year, I also read a book called Something Personal by Norma Stevens. It goes through Richard Avedon's life. So that was just really interesting to me to hear some of the antidotes and behind-the-scenes.

Going back to history, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an autobiography. It is pretty short, so I read it a couple of times. It really was impactful for me to learn more details about his life: how he got out of slavery, how educated he was, and specifically, his mindset around photography. He was the most photographed person in the 19th century. And the reason he wanted to be photographed was because he wanted people to understand what a Black person who's educated and powerful and strong looks like. Because he knew how powerful photography and the power of images were.

---------------

What are the challenges that you face as a freelancer?

I think figuring out an economic model that's going to be self-sustaining.

I do print sales, editorial work, workshops, and private commissions. I love to do this work, but how can I make enough money to live off of it without sacrificing what my true intent is? I think the biggest challenge is figuring out a way to generate enough income, that is sustainable, and a real business that turns profit. It's figuring out how to do that and how to do it consistently.

I am in a different situation since I do have a full-time job, too. I still look at it as a business, and I am trying to obviously turn a profit as much as I can. It is definitely very challenging. It is tough to make it out there as just an editorial-only photographer. All photographers these days have to do multiple things or have multiple streams of income with their photography.

---------------

I think figuring out an economic model that's going to be self-sustaining.

I do print sales, editorial work, workshops, and private commissions. I love to do this work, but how can I make enough money to live off of it without sacrificing what my true intent is? I think the biggest challenge is figuring out a way to generate enough income, that is sustainable, and a real business that turns profit. It's figuring out how to do that and how to do it consistently.

I am in a different situation since I do have a full-time job, too. I still look at it as a business, and I am trying to obviously turn a profit as much as I can. It is definitely very challenging. It is tough to make it out there as just an editorial-only photographer. All photographers these days have to do multiple things or have multiple streams of income with their photography.

---------------

What else feels important to share?

As storytellers, we have our own personal stories, but being in a position to help to tell someone else's story with their consent is really powerful, too.

I would encourage photographers out there, whatever story you want to tell, or a story that hasn't been told - you with your viewpoint - you should tell it, and you should get it out there. Because I think that's how you make a difference with photography, by promoting awareness. And then, hopefully, that awareness will lead to a change in some way, shape, or form.

---------------

As storytellers, we have our own personal stories, but being in a position to help to tell someone else's story with their consent is really powerful, too.

I would encourage photographers out there, whatever story you want to tell, or a story that hasn't been told - you with your viewpoint - you should tell it, and you should get it out there. Because I think that's how you make a difference with photography, by promoting awareness. And then, hopefully, that awareness will lead to a change in some way, shape, or form.

---------------

Visura: Rashod Taylor on Documenting the Intimate Realities of Family, Legacy, and the Lens

10,684