I listened. I carried her warnings home like a sacred text, unseen but absolute.

In the days after, I picked my plate clean, leaving no trace of bone. In the bathroom, I rushed through my showers, my breath shallow, my skin prickling with a presence I could not see but could not unfeel. The darkness in my room was no longer empty; it had depth, shape, intention. I lay in bed, stiff as stone, listening to the silence until it became a sound of its own.

My father noticed. *What are you afraid of?* he asked.

I told him. Expecting him to confirm it. Expecting him to tell me how to keep myself safe. But he only looked at me and said, That is your teacher’s imagination, not yours. She sees the world one way, but you don’t have to.

But wasn’t I already seeing it her way? Her ghosts had folded themselves into my vision, into my body. I could not unlearn them, could not unknow them.

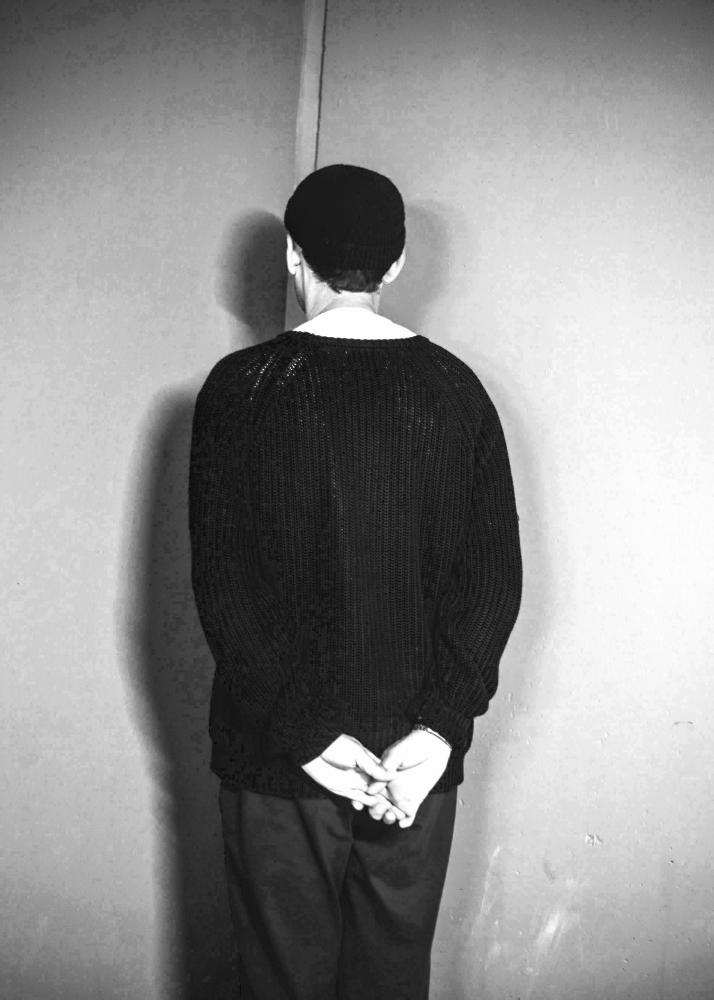

So I placed myself in the dark. I stood still, letting the silence settle over me like dust. If I don’t move, will it move first? I thought. If I let the fear rise, will it take form? If I blink, will something blink back?

I waited. I listened. I imagined.

And now, as an adult, I still ask the same question. I see all reality around me—political, social, economic—not as something solid, but as an imagination passed down, a dream of someone long gone. A delusion, structured and enforced, until we all followed it as truth. What difference is there between a child fearing ghosts in the dark and a society fearing the collapse of an illusion?

If fear is imagined, what else is? If fear isn’t real, then what is?