Project Text

In a passageway in the Las Margaritas neighbourhood of Soyapango, a group of men struggle to force another man into a van. They grab him by the arms, neck and legs, but he resists — it is clear that he does not want to leave. Seconds later, despite the man’s attempt to break free, they manage to get him into the vehicle. From another car, located a few meters from the scene, a woman records with her cell phone. Her companion asks her to call the police, but the woman continues recording. Minutes later, the group of men were arrested by the National Civil Police and spent more than a week detained by the local government in Soyapango.

The video

went viral after being posted on an X account that shares information about police operations. The account portrayed the event as a possible kidnapping. Still, a few comments cast a different light on the matter: “Violent

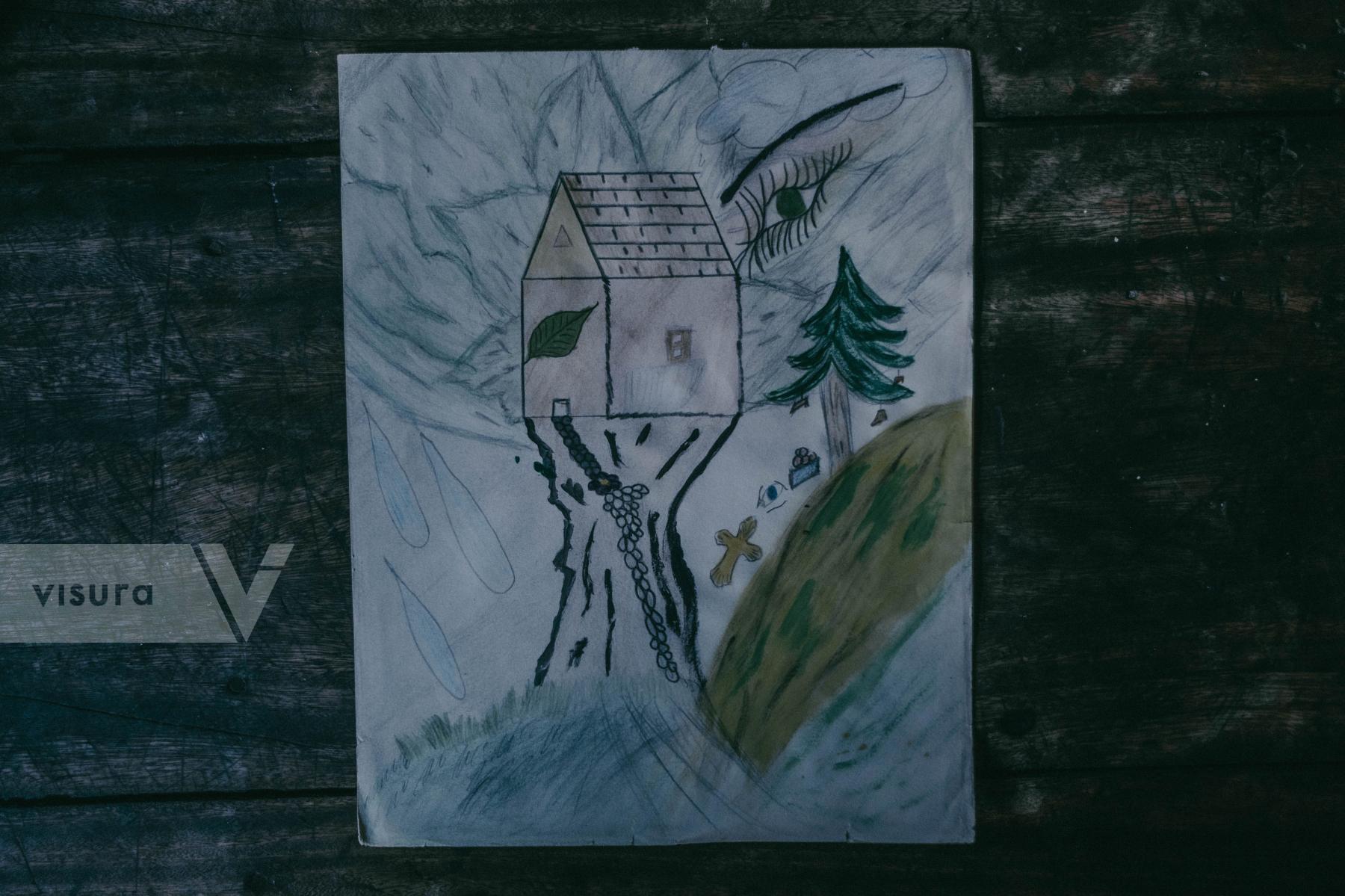

drogo[drug user or junkie],” “taken away for rehabilitation,” “what good friends.”These men were not kidnappers. Evidently, they carried the man against his will, but their goal was not to ask for ransom. In fact, all of them were released after the family, along with the captured man himself, explained to police that it was an attempted “rescue” from an alcohol addiction. The “rescue” was carried out by members of a rehabilitation center that operates in the Santa Anita neighborhood, in the center of San Salvador, under the name El Brit, a Hebrew word meaning “pact.” The center’s catchphrase is “children of chaos.”The center began operations in 2020 and, according to its members, specializes in addiction prevention and treatment and the social reintegration of people suffering from alcohol or drug addiction. And yes, sometimes, as shown in the video, its methods entail forcing the person to seek help.

When a family calls El Brit, the center sends a team to speak with the person. El Brit’s collaborators recognize from their own experiences the behavior of an addict. First, they warn the person that their family is suffering and try convincing them to seek treatment. Before this discussion, relatives must sign a document authorizing El Brit to take —voluntarily or by force— the person suffering from an addiction. That only happens, however, in very specific cases; most people come voluntarily after suffering the physical and social ravages of their addictions.

According to official data from the

2023 National Report on the Drug Situation, in the first six months of the year, 5,942 emergencies due to acute poisoning and overdose were attended to in El Salvador. Alcohol poisoning was the highest number of cases, followed by tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, sedatives, amphetamines, opioids, and hallucinogens. The same report reveals that in 2022, there were 291 deaths related to mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol use. Ninety-four percent of the people who died were men.

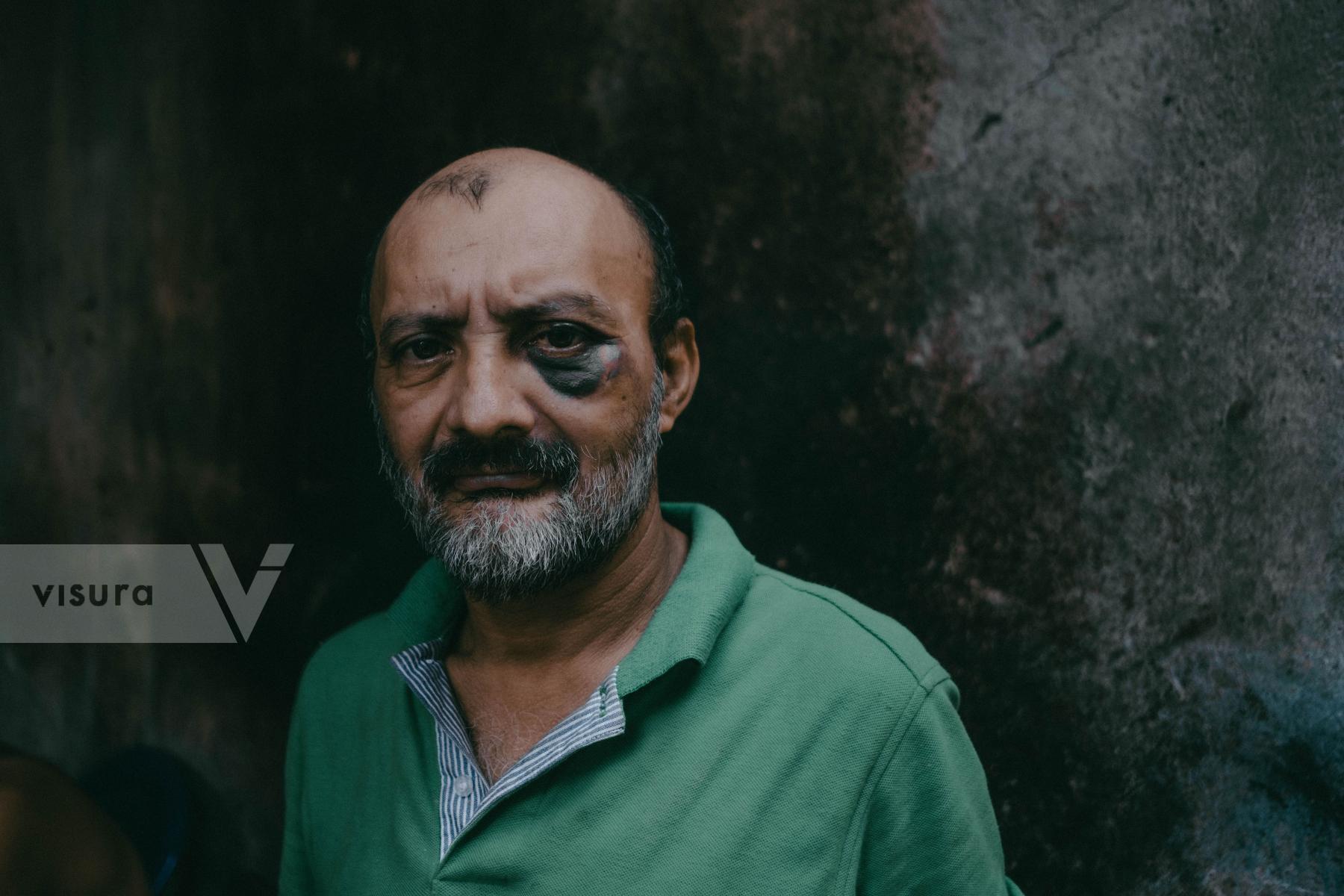

In 2022, only seven prevention and treatment centers existed in Fosalud (a nationally funded provider of specialized health services) facilities across the country, along with ten other rehabilitation centers formally approved by the National Anti-Drug Commission. Outside of the healthcare system, non-approved private or NGO institutions such as El Brit exist. Eighty men are currently undergoing the rehab process at El Brit. Some of them are from the rural parts of the country or were deported from the United States and have no relatives in El Salvador. Many suffered from migration-related abandonment as children. The majority have lost their jobs due to their addiction.

At El Brit, activity begins early in the day. Some cook; others clean. Those who are weakened from the withdrawal process rest. The sick are taken to the hospital. In the afternoons, people play cards, exercise, and hold group discussions. Call center workers, farmers, deportees, and university students converge there. Thus begins a long journey of up to six months of confinement for these men to try to rehabilitate themselves.