Events

News

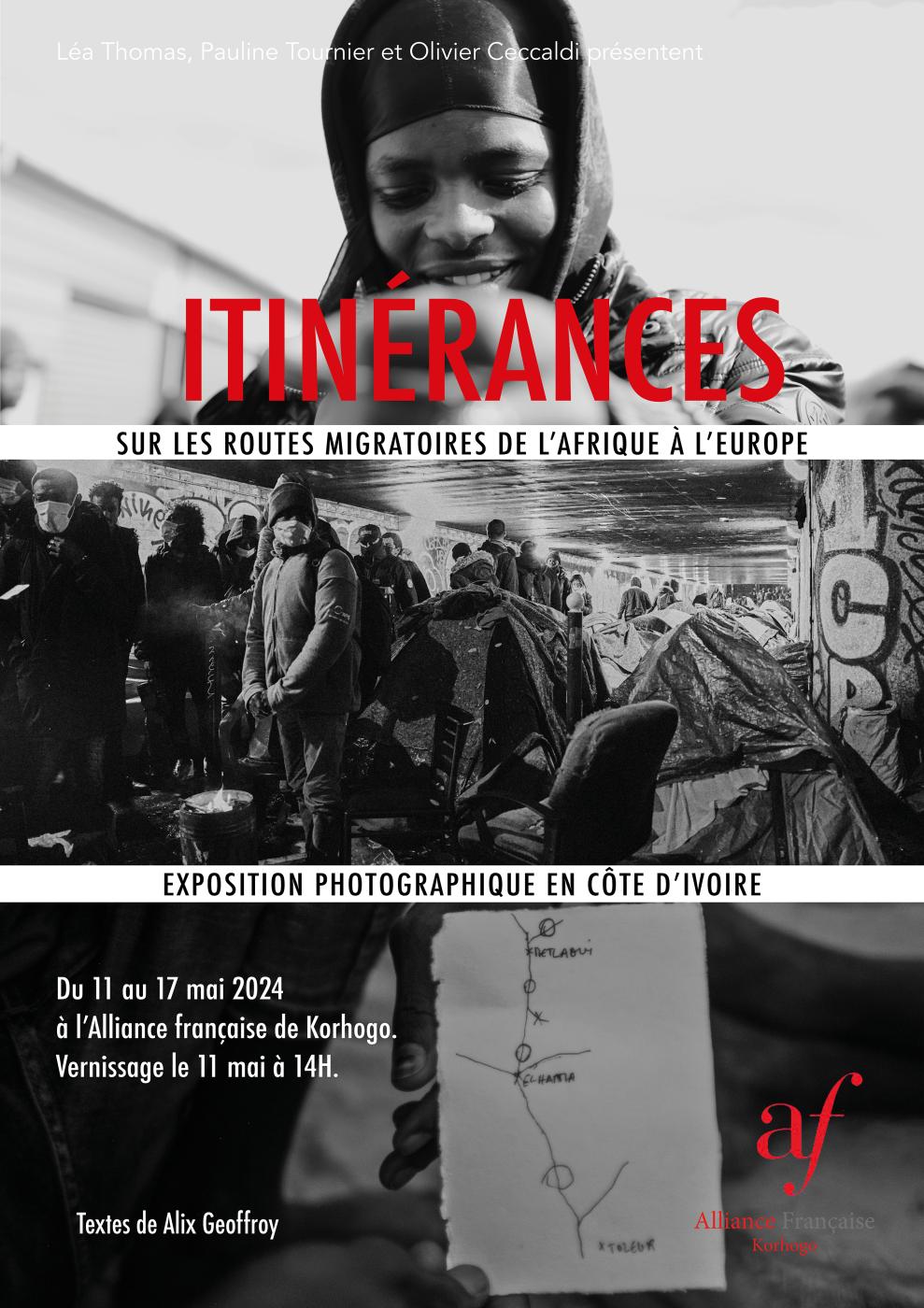

Itinérances

olivier ceccaldi

Jan 18, 2025

Ce travail a fait l'objet d'une exposition dans les locaux de l'Institut français de Korhogo en Côte d'Ivoire et a donné lieu à une discussion ouverte avec les habitants autour des raisons qui poussent les gens à prendre la route.

Texte d'Alix Geoffroy qui accompagnait les photos lors de l'exposition

Au début du voyage, Ibrahim se répétait en pensée la liste des pays traversés dans l’ordre chronologique, du départ à l’arrivée. Parfois même il la disait tout bas, mais alors il a remarqué qu’il lui fallait reprendre son souffle juste avant de dire “Royaume-Uni”. Depuis, il répète la liste dans l’ordre inverse, en commençant par l’objectif : Royaume-Uni, France, Italie, Tunisie, Algérie, Mali, Sénégal. Quand il prononce “Mali”, les images du Sahara défilent à toute vitesse dans sa tête - deux syllabes pour le pays, trois pour le désert, et un monde entier de souvenirs. Il n’arrive toujours pas à croire que pour décrire la traversée de la mer entre la Tunisie et l’Italie, il n’y a qu’une virgule, seulement une toute petite pause entre les deux mots quand il les prononce, rien de plus qu’un espace quand il les écrit.

À Lampedusa, à peine quelques minutes après l’arrivée de leur bateau, Ibrahim a vu un jeune Soudanais, d’à peu près son âge, au téléphone avec sa famille. Il tremblait, pleurait, faisait les cent pas pour tenter d’épuiser toute la peur panique qui habitait son corps quelques instants auparavant. Ibrahim le regardait en serrant les dents - jamais il n’aurait fait subir cette angoisse à ses parents. Après avoir attendu plusieurs heures, pour que le rythme de son cœur revienne à la normale, pour que ses mains cessent de trembler, pour que le son de sa voix devienne suffisamment assuré, régulier et calme, il les a appelés. Il pensait surtout à Awa - il sait qu’elle ne comprend rien à ses mots, mais tout à ses intonations. Toujours dans les bras de sa mère, elle aurait tout entendu s’il avait téléphoné alors qu’il était encore aussi choqué que ce Soudanais, qui ne pensait à rien.

En mer, la plus grande peur d’Ibrahim est venue quand il a pensé à sa sœur. Il a entendu les soubresauts du moteur, il a pensé : “Si je me noie maintenant, Awa ne se souviendra peut-être même pas de moi quand elle sera grande”. Le moteur a hésité, a été secoué de quelques hoquets, et puis il a démarré de nouveau. Plus tard, en marchant sur la terre ferme, en parlant à Awa qui le regardait à travers les deux écrans interposés, Ibrahim a pensé que bientôt elle ne le reconnaîtrait plus. L’année précédente, à l’école, il a étudié un extrait des Lettres Persanes de Montesquieu, dont il a retenu cette phrase : “Heureux celui qui, connaissant tout le prix d'une vie douce et tranquille, repose son coeur au milieu de sa famille, et ne connaît d'autre terre que celle qui lui a donné le jour.” Quand il pense à l’école, il a l’impression que c’était il y a des millénaires.

Un soir, alors qu’il avait appelé ses parents et sa soeur, et que le réseau internet l’empêchait de voir et d’entendre les siens, et d’être vu et entendu d’eux une fois de plus, Ibrahim a imaginé qu’il était chez lui, dans la maison de son enfance, parmi sa famille, mais invisible et inaudible, comme le réseau internet lui imposait de l’être. Des pans entiers de son quotidien étaient de fait invisibles et inaudibles pour sa famille : il n’a jamais dit qu’il dormait dehors, ni en Tunisie, ni en Italie, ni en France. Dans le désert, à Tozeur, à Sfax, à Tunis, à Paris et à Saint-Denis comme à Calais, il était toujours en mouvement et devait inventer des mensonges. Il n’a jamais parlé des passeurs, ni des policiers, ceux qui emportaient leur argent et leurs tentes, et voulaient qu’ils aillent toujours ailleurs. Il n’a pas mentionné les files d’attente interminables pour se nourrir, se laver, se soigner. Il ne parlait que du grand royaume, et de tout ce qu’il pourrait faire pour sa famille une fois arrivé.

À Calais, accueilli à la maison Margelle, il était heureux de dormir dans un vrai lit, mais encore plus de pouvoir dire la vérité. Maintenant, Ibrahim regarde cette seconde mer qui le sépare du premier pays de la liste. Il réussira à la traverser aussi. Royaume-Uni, France, Italie, Tunisie, Algérie, Mali, Sénégal.

Itinérances is a collective project by photographers Léa Thomas, Pauline Tournier, and Olivier Ceccaldi. The project tells the fictional story of a young Senegalese man embarking on a journey across Africa to reach Europe, based on photographs that document the harsh realities of the migration route. Between Senegal, Tunisia, Paris, and Northern France, Itinérances portrays a story of hope while immersing us in the daily lives of those seeking to reach Europe. This work was exhibited at the Institut français in Korhogo, Ivory Coast, and sparked an open discussion with local residents about the reasons why people embark on such dangerous journeys.

Text by Alix Geoffroy accompanying the photos during the exhibition:

At the beginning of his journey, Ibrahim repeatedly mentally listed the countries he crossed, in chronological order, from departure to arrival. Sometimes he even said it out loud, but he noticed that he would catch his breath just before saying "United Kingdom." Since then, he reversed the order and began reciting the list starting with his goal: United Kingdom, France, Italy, Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Senegal. When he says "Mali," the images of the Sahara race through his mind—two syllables for the country, three for the desert, and a whole world of memories. He still can't believe that to describe the crossing of the sea between Tunisia and Italy, there’s just a comma, a tiny pause between the two words when he says them, no more than a space when he writes them. In Lampedusa, just minutes after their boat arrived, Ibrahim saw a young Sudanese man, about his age, on the phone with his family. He was trembling, crying, pacing back and forth, trying to exhaust the panic that had taken over his body moments before. Ibrahim watched him, gritting his teeth—he would never have subjected his parents to such anguish. After several hours of waiting, until his heart rate returned to normal, until his hands stopped shaking, and until his voice became steady and calm enough, he called them. He thought mostly about Awa—he knew she wouldn’t understand his words, but she would understand his tone. Still in her mother's arms, she would have heard everything if he'd called when he was still as shaken as that Sudanese man, who thought of nothing. At sea, Ibrahim’s greatest fear came when he thought of his sister. He heard the engine sputter and thought, “If I drown now, Awa might not even remember me when she grows up.” The engine hesitated, sputtered a few times, and then started up again. Later, when walking on solid ground, speaking to Awa, who was watching him through two screens, Ibrahim thought that soon she might not recognize him anymore. The year before, at school, he had studied an excerpt from The Persian Letters by Montesquieu, where he remembered this line: "Happy is he who, knowing the value of a calm and peaceful life, rests his heart among his family, and knows no other land than the one that gave him birth." When he thinks of school, it feels like it was millennia ago. One evening, after calling his parents and sister, with the internet connection preventing him from seeing and hearing them, from being seen and heard by them once more, Ibrahim imagined he was back home, in the house of his childhood, among his family, but invisible and inaudible, just as the internet connection made him be. Entire parts of his daily life were in fact invisible and inaudible to his family: he never said he slept outside, neither in Tunisia, Italy, nor France. In the desert, in Tozeur, Sfax, Tunis, Paris, Saint-Denis, or Calais, he was always on the move and had to invent lies. He never spoke about the smugglers, nor the police who took their money and tents and forced them to go elsewhere. He didn’t mention the endless lines to get food, wash, or seek medical care. He only talked about the grand kingdom and all he could do for his family once he arrived. In Calais, when welcomed at the Maison Margelle, he was happy to sleep in a real bed, but even more so to be able to tell the truth. Now, Ibrahim looks at the second sea that separates him from the first country on the list. He will cross it too. United Kingdom, France, Italy, Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Senegal.

Text by Alix Geoffroy accompanying the photos during the exhibition:

At the beginning of his journey, Ibrahim repeatedly mentally listed the countries he crossed, in chronological order, from departure to arrival. Sometimes he even said it out loud, but he noticed that he would catch his breath just before saying "United Kingdom." Since then, he reversed the order and began reciting the list starting with his goal: United Kingdom, France, Italy, Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Senegal. When he says "Mali," the images of the Sahara race through his mind—two syllables for the country, three for the desert, and a whole world of memories. He still can't believe that to describe the crossing of the sea between Tunisia and Italy, there’s just a comma, a tiny pause between the two words when he says them, no more than a space when he writes them. In Lampedusa, just minutes after their boat arrived, Ibrahim saw a young Sudanese man, about his age, on the phone with his family. He was trembling, crying, pacing back and forth, trying to exhaust the panic that had taken over his body moments before. Ibrahim watched him, gritting his teeth—he would never have subjected his parents to such anguish. After several hours of waiting, until his heart rate returned to normal, until his hands stopped shaking, and until his voice became steady and calm enough, he called them. He thought mostly about Awa—he knew she wouldn’t understand his words, but she would understand his tone. Still in her mother's arms, she would have heard everything if he'd called when he was still as shaken as that Sudanese man, who thought of nothing. At sea, Ibrahim’s greatest fear came when he thought of his sister. He heard the engine sputter and thought, “If I drown now, Awa might not even remember me when she grows up.” The engine hesitated, sputtered a few times, and then started up again. Later, when walking on solid ground, speaking to Awa, who was watching him through two screens, Ibrahim thought that soon she might not recognize him anymore. The year before, at school, he had studied an excerpt from The Persian Letters by Montesquieu, where he remembered this line: "Happy is he who, knowing the value of a calm and peaceful life, rests his heart among his family, and knows no other land than the one that gave him birth." When he thinks of school, it feels like it was millennia ago. One evening, after calling his parents and sister, with the internet connection preventing him from seeing and hearing them, from being seen and heard by them once more, Ibrahim imagined he was back home, in the house of his childhood, among his family, but invisible and inaudible, just as the internet connection made him be. Entire parts of his daily life were in fact invisible and inaudible to his family: he never said he slept outside, neither in Tunisia, Italy, nor France. In the desert, in Tozeur, Sfax, Tunis, Paris, Saint-Denis, or Calais, he was always on the move and had to invent lies. He never spoke about the smugglers, nor the police who took their money and tents and forced them to go elsewhere. He didn’t mention the endless lines to get food, wash, or seek medical care. He only talked about the grand kingdom and all he could do for his family once he arrived. In Calais, when welcomed at the Maison Margelle, he was happy to sleep in a real bed, but even more so to be able to tell the truth. Now, Ibrahim looks at the second sea that separates him from the first country on the list. He will cross it too. United Kingdom, France, Italy, Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Senegal.

534