Schools have a particular smell about them; it nests quietly in the corners of the building. It’s made of a variety of things—markers, paper, ink—but there is one smell that may be most significant of all, sitting in children’s soles, the smell of sneakers transporting students from class to class and grade to grade, from recess to detention and teacher to parent. In sneakers, students become the blood pumping through hallways like blood through veins. The squeaking of rubber and new plastic between a child’s foot and the polished stone floor is the sound of life and hope. It is the sound of paper tacked to a wall, rustling like the wind blowing through the leaves of trees as a student runs by, the papers lifting upwards for a moment before settling back against the corkboard.

When I was in elementary school, I begged my mother for a pair of Nike tennis shoes. I wanted to be a cool kid with a pair of Nikes; at least, that is what I thought I wanted to be. My mother finally bought my coveted pair of Nikes at a shoe outlet after a great deal of bargaining on my part. But, by the time I finally got them, I was no longer interested in being a girl with a nice pair of Nikes. I’d moved on to a pair of heavy black, faux leather Patti Smith boots that doubled the weight of my step two-fold as I clomped through the hallways and playground. I still own the Nikes to this day, and I still wear them, too; the black leather boots, not so much. My Nike tennis shoes had the same rubber that transported me through my school’s hallway. The students of Stanton are no different from me; they want to wear Nike tennis shoes, too. But more importantly, like me, they also want to learn.

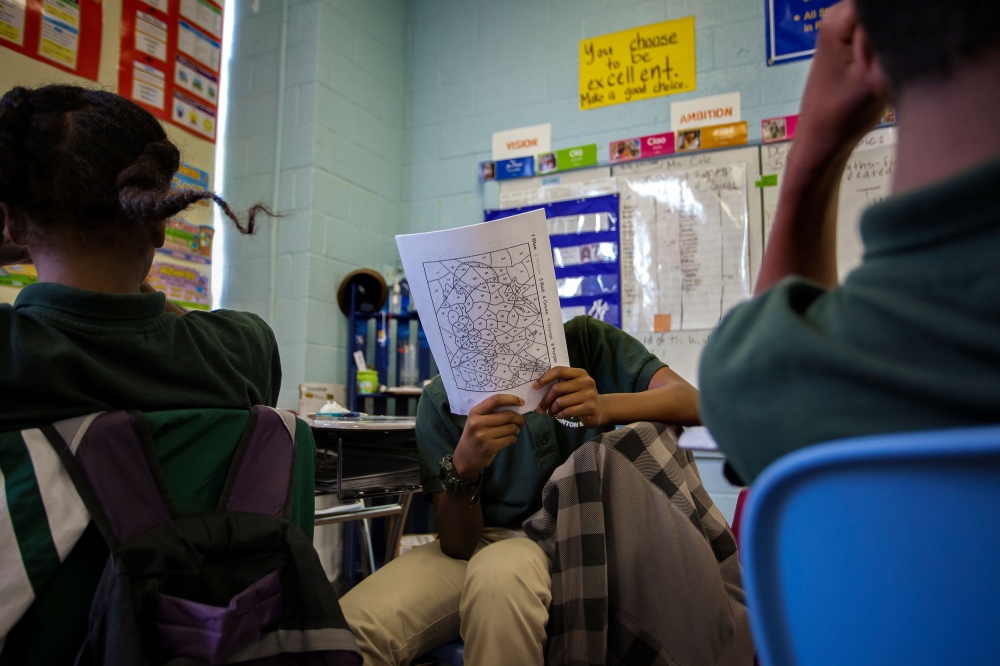

The students of Stanton Elementary like to wear loose fitting hoodies and bubbly coats patterned with checkerboard designs, logos for sports teams and bright red, green and blues and dark purples, blacks and navies. It is a yelp of expression against their school uniform of khaki pants and forest-green collared shirts that say “Stanton DC Scholars.” On the playground, I see a boy wearing a multicolored coat that looks like a still frame of the video game Tetris. I was later told the coat cost $150. I remembered my own longing for what was then called a “Starter Jacket,” a large, bubbled jacket that made the wearer look something like a multicolored marshmallow. Mine had a University of Kentucky Wildcats theme; the Wildcats are a local college team, more like a religious cult than a sports team to Kentuckians. That coat not only kept me warm, it allowed me to fit in at school, and, more importantly, it gave me a connection to my father, who loved the team.

The Stanton students in their oversized coats and untied Nike shoes reflect the neighborhood outside of the classroom window. The Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C., is speckled with Dollar Stores, small barbershops and salons, McDonalds, Lee’s Chicken restaurants, and Section Five housing.

I came to Stanton Elementary because I wanted to understand how failing public schools in America could begin to improve. In the disenfranchised neighborhood of Anacostia, improving schools has never been more important. So many of the people in the southeast neighborhood of Washington, D.C., struggle from day-to-day, with no hope of parole. Stanton Elementary has become an oasis of relative calm in this agitated neighborhood.

As I drive across the 11th St bridge each week from the Northwest side of Washington, D.C., I realize how beautiful Anacostia can be in the fall, when the yellow and red leaves of the neighborhood’s old trees make the earthen red brick of the old apartments glow and the black steel bars that obscure windows disappear.

Too many schools seem to operate like bad zoos, herding loud, bored, and emotionally stunted and disrespectful children from room-to-room, with a brown meal mid-May. These students are pushed from grade to grade, passed along like bad news to the next teacher, turning good teachers into babysitters. Potential doctors become petty thieves, scientists become cashiers, artists become addicts, computer programmers become teenaged parents and college professors are incarcerated.

As I think about Stanton Elementary, I cannot help thinking back to my own elementary, middle and high school experiences. I can see the yellow and grey halls of my high school now. Grey marble floors giving way to narrow orange lockers that were speckled with graffiti, large pale oak doors, that open up into clean and organized classrooms. By my senior year of high school, I could not wait to get out. But unlike some students who dropped out in frustration with a system that ignored and ridiculed them, I realized the shortcomings of the system and looked for alternatives to it. With determination, I was able to arrange my schedule so that I only had to spend an hour a day at my school. The rest was spent taking math classes at the local university and working at a local pizza parlor. My teachers were not happy with my choice, but I never regretted that decision. However, I saw smart, talented, kind and wonderful friends cast into shapes and identities they were not meant to have. I think about them sometimes, and about how I was lucky enough to have supportive parents to counteract a school that wished to turn me into a mass-produced American worker. I think about how I escaped and how I wish I could have helped my old friends escape, too. I recently spoke to an old high school friend of mine who, when asked to give details about his life after hearing about mine, simply said, “Just working, raising my kid. Trying to find time to finish school. I assure you that your life is more interesting than mine.”

For a time, Stanton was part of this system of mis-education. It was known as the second worst school in the District of Columbia. But three years ago, Stanton, with its angular, brick façade sitting on a teardrop shaped lot in the middle of town, got a makeover—a second chance. Its corners still bleed a dirty black from decades of breathing city air. The square football and baseball field still pushes sharp corners to the edges of the street to fit itself within the block, trash strewn along the field, scoring points where there were none. But now, Stanton’s brick bones seem to reach higher. Its dusty bruises are only a reminder of what was. The large, old oak trees at the entrance of the school now seem like arms reaching out to students, asking them to come learn. The field behind the school beckons to students who see themselves as football players and future college students. Homework nips at the heels of students as they run across the short, painted Bermuda grass. A few years ago Stanton had a light shone on it and was given the opportunity to change. The change has been hard fought, but it continues. I drive up to Stanton early one pink and grey morning in my rented car, my camera equipment neatly packed in a worn army green messenger bag sitting on the passenger seat beside me, a coffee cup clutched in my right hand. I know that in the far back corner of the school at the top of the stairs there is a beacon of light: Ms. Tillman’s classroom. The light of any good school is a great teacher; the students are the mirrors of a teacher, reflecting the light that is shown on them.

Ms. Tillman teaches reading. Four years ago, Stanton’s reading scores were deplorable in a District whose scores were at 17% proficiency overall in 2011. As part of Stanton’s turnaround program, the D.C. Board of Education removed 97% of Stanton’s staff, including all of the teachers, and replaced them with a new, younger teaching staff. It set a clear five-year goal to improve the school’s testing scores.

This history of disenfranchisement is still visible in Ms. Tillman’s class. I see the look of concern in her eyes as she works tirelessly with fourth grade students who are still at a kindergarten reading level.

“It’s hard to see our babies move on without the proper reading skills” she says, “I worry about them all the time.”

Ms. Tillman’s classroom is behind two heavy oak doors that are painted green and blue. Like the entrance doors of the school, they squeal loudly when opened or closed. The classroom is a jumble of brightly colored paper, with desks and cubbies spread across every inch of available space. A white board dominates the front wall of the room and is covered with learning objectives, rules and, most interestingly, an “income chart” with each student’s name written on it.

Stanton has a system of daily rewards and reprimands for student behavior. For good behavior and strong work habits, money is added to a student’s “paycheck.” For poor behavior money is taken away. Depending on the amount of money a student has in his or her paycheck, he or she is allowed in or excluded from educational field trips and pizza parties. The paycheck system teaches students that professional behavior and a good work ethic are fundamental building blocks to success. Day after day, I hear Ms. Tillman say, “Add $5 for the whole class” or “$10 off Imani, $10 for Elijah, $15 off everyone, please do not talk in the halls!”

I am amazed at Ms. Tillman’s patience. I am amazed at the idea that a fourth grader in America can barely read; I can’t remember a time when I didn’t voraciously gobble up books.

To the left of the whiteboard is a window-filled wall that looks out over a McDonald’s and Lee’s Chicken. Large sheets of paper showing old lessons cover much of the dingy windows with tan, moldy blinds. Colorful laminated posters show hands portraying different signing symbols. Stanton has adopted sign language that is used in the classroom, in lieu of verbal communication, which can at times cause students to get off topic and send classes into loud chaos.

There are four main statements in this language that students can use during class discussion, including, ‘I have a question,’ ‘I disagree,’ ‘I agree,’ and ‘Great job!’ A student making a fist and raising a pinky finger symbolizes ‘I have a question,’. This sign is sometimes replaced by, ‘I am confused,’ which is the most complicated of the signs and involves a student taking his or her pointer finger and touching the chin, then closed fist and raising a finger in the air. ‘I agree” is signed by making a fist and extending out the thumb and pinky finger, much like the ‘aloha’ symbol, and is usually accompanied by a smile. ‘I disagree,’ or ‘I have the answer,’ is simply signed by making a fist. My favorite sign is when students tell each other ‘Great job,’ which is always accompanied by a large smile and muted excitement. The sign is simply the shaking of both hands, palms open. The students love signing. They shake their hands violently throughout class discussion time; their eyes widen and shine.

At the end of a long day of observation at Stanton, I sit with Ms. Tillman after school as she tutors struggling students on fundamental reading skills.

“Today we are working with the form ‘am’. When I say a word, please spell it. Am, bam, ham, jam, Pam, Sam. Now read these words for me: at, bat, cat, fat, vat…”

During these lessons Ms. Tillman works with a young girl who struggles to read the name Al. She reads it as ‘la’ or ‘all.’ “Al. It is a person’s name,” Ms. Tillman says. “Al,” repeats the young girl softly.

Seeing children left behind is far more jarring than simply holding the statistic in my head. I notice, too, that despite these students’ difficulties in reading, they still search for books constantly and love nothing more than to impress a teacher who has caught them reading in the halls and on the playground. A year ago, Stanton had a program called “Caught Read Handed,” which promoted and rewarded students for extracurricular reading.

When I was in kindergarten, my mother bought a book for me called The Giant’s Farm. “This is a big kid’s book. Someday, when you are older, you will be able to read it,” she told me. The book became a goal for me, it was something I imagined only a 16 year old would read; however, I was much closer to being able to read the book than I knew. Only a month later, I was reading about the friendly giants and their love for farming, building and baking. I kept that book for a very long time. It made me feel like I had accomplished something great.

Ms. Tillman is no stranger to the problems in America’s education system. She witnessed it first-hand when she was a student. She attended Pittsburgh’s Oliver High School, a school made infamous in the documentary film Waiting for Superman that labeled it a ‘Dropout Factory.’

“These students don’t realize that I know where they are coming from. I am from the ghetto, too.” Mrs. Tillman tells me. I once asked her, “How did you get out of your bad school?” “I don’t know how I got out,” she answers. “My mother had a terrible experience with her education and never emphasized its importance to me.”

Ms. Tillman explained how her sister’s children are not yet in school but already know the alphabet and can write small words. “None of our students come in with that knowledge,” she said. This idea that education must happen at home and school is the core of Stanton’s new philosophy. Ms. Tillman and her colleagues visit student’s homes during the summer and work with the parents and the students to encourage learning.

“The parents used to be as bad as the students, they would curse us out and be disrespectful and thought that we were just another group of teachers that would move in and move out, making no change at all. But after years and years of us telling the students the same thing and pushing the same high expectations, things have started to improve—slowly.”

I sat on the hallway floor with three students one afternoon between classes. The students talk about what they want to be when they grow up and where they want to go to college. “I’m not gonna’ drop outta school!” proclaims one tall young boy in a knit cap. “I want to stay at Stanton,” says another young small boy with dreadlocks, “I don’t want to go to no bad school no more!” Sometimes when I am at Stanton, I take time to walk through the halls and look in on classrooms. I think about the students of Stanton who were given a second chance. I think about the former students of Stanton who never got a chance to succeed. I wish we could go back and help them too. When I look in on Ms. Tillman’s class, with eager students looking up at her and clinging to her every word, I smile. Then I hear the rapid clomping of student running in the hallways. “Stop running,” a custodian says gently. The student slows down, grips his books to his chest, and shuffles quietly but eagerly into a classroom.

Transition is not easy, but Stanton is like the little engine that could, quietly saying to itself, “I think I can, I think I can, I think I can, I think I can…” It is only a small way up the hill, but it keeps on chuggin’.