RIO GRANDE RESERVOIR, Colo —Farmer Kyler Brown in front of a small dam on the Rio Grande at a farm outside of Monte Vista, Colorado. “I’ve ranched. I’ve cowboyed. Now I’m farming and ranching,” Brown said. “You quickly learn in the West how important water is.” (Photo By Diana Cervantes for Source NM).

The river pools into the Rio Grande Reservoir at the base of the San Juan Mountains, fed mostly by snowmelt. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

An old train depot captured June 22, 2022 outside of La Jara, Colorado. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A drip sprinkler system feeds barley in a farm at Monte Vista. Most drip irrigation uses groundwater, a shrinking resource in the San Luis Valley. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Even as the valley had record-breaking monsoon rainfall in 2022, it isn’t enough to recharge the aquifers, which face decades of pumping more water than is sinking in. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

RIO GRANDE NATIONAL FOREST — Beetle-bitten fir and spruce, along with burn-scarred aspens, are part of the fabric of the forest around the Rio Grande headwaters. Forests across the western U.S. are facing a triple threat, weakened by drought, decimation from pests and devastation from wildfires. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Bark falls away from a dead Engelmann Spruce tree, exposing beetle trails and the tree’s vulnerable vascular system. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

New growth pushes up from the understory of a burned aspen grove at the Rio Grande headwaters. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

MONTE VISTA, Colo. — Kyler Brown drives a calf on June 21, 2022 as part of a drive that went through downtown Del Norte, Colorado. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Kyler Brown and his son Elijah Brown go over the schedule for the day on June 21, 2022, before Kyler heads to the cattle drive. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Kyler Brown helps wife Emily Brown put on boots before the cattle drive the morning of June 21, 2022. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Cows can be seen amid alfalfa fields during the cattle drive on June 21, 2022. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Emily Brown riding through downtown Monte Vista during the cattle drive. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The Browns and Rider Off, 10, take a break after the cattle drive. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Kyler Brown stands atop an irrigation sprinkler on the Monte Vista, Colorado property. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Kyler Brown, a farmer in the San Luis Valley, looks on the cottonwood stands on his father-in-law’s property along the Rio Grande in Monte Vista. “It makes me sad to go through drought, but every other year is drought.” (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The Brown’s ride to their neighbors, the Off’s, property to help drive some cattle. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Kyler Brown releasing two of his bulls on a property he rents from in Del Norte. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A shed near the cattle drive pasture in Del Norte. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

MANASSA, Colo. — JD Schmidt’s sheep graze in the San Luis Valley on June 23, 2022. Drought has impacted every part of agriculture in the valley. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Hector Sandoval cares for JD Schmidt’s sheep in the San Luis Valley. Sandoval said the consecutive years of drought have been hard on the herd. In the spring, “We had to feed them. There wasn’t always enough grass,” he said. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

MONTE VISTA, Colorado — Linda Schoonover cradles one of her geldings on her ranch outside of Monte Vista. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Linda Schoonover says she learns a lot from the animals she raises and cares for, “If you ever look in a cow’s eye, or a horse’s eye, you see a wisdom there that they know something you don’t know,” she said. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Some of Schoonover’s cattle on her property. Her herd of Black Irish Angus and Longhorns is down to 50. In years past, she ran between 500 and 600. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Schoonover drinks coffee the morning of June 23rd, before irrigating her field. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A collection of items in Schoonover’s kitchen window. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Schoonover releasing sheep to pasture in the early morning of June 23. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Schoonover standing in her field where she cares for a small creek that runs through it. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Schoonover and her dogs out in her field as she makes cuts in the field to let the water soak in. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Jack, one of Schoonover’s six dogs that are her constant companions. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

“I think while we’re here on this great Earth, we’re stewards,” she said. “You don’t be a big old slob. You don’t blow things off. You take care of things to the best of your ability.” That means establishing limits, she added — something society has been reluctant to do. “How do you stop growth?” she asked. “That’s the question to end all questions in the West.” (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Ranching keeps her grounded. When she’s making cuts in the ditch to pour water into the alfalfa meadows, when she’s hunting for worms or nursing a calf, it connects her to tradition. For her, that tradition also means conservation. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Schoonover and her dogs preparing to care for the pasture. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

LAS MESITAS, Colo. —Alfalfa blooms in the fields next to the shell of the San Isidro Catholic Church, which burned in 1975. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Chris and Lucilla Cisneros, married for 55 years, live just up the road from the San Isidro Catholic Church. In that time, the land has changed around them, marked by drought and fire. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Lucilla Cisneros pulls tumbleweeds from the cage around the older graves in the churchyard. "We care for them as if they're our own." (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Chris and Lucilla Cisneros pull away from the crumbling church and its cemetery after their work is done. The couple has been caring for these grounds for 35 years, but the work has grown harder as the land and climate shift. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A carpet of grass fills the aisles of the church, open to the elements for nearly 50 years. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — The oxbow, a horseshoe curve of the river that has transformed over time into a marsh, as seen from the San Antonio Bluffs on Albuquerque’s Westside. Consecutive years of drought dried parts of the marshland that are crucial habitats for birds, beavers and other animals. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe checks his traps for beetles, as part of fieldwork examining ground arthropods and groundwater levels in the marsh. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Cottonwood seeds float across the air, borne aloft on summer winds. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe rests on the banks of the Rio Grande among coyote willow and salt cedar. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe pushes through a thicket of plants, twists of coytoe willow, and invasive plants such as Russian olive and salt cedar. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe, a graduate student in Water Studies at the University of New Mexico, tends to plants in the campus greenhouse. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe checks a Donkey's Tail succulent at the UNM greenhouse. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Wes Noe cuts back a lemon tree. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The UNM greenhouse seen beyond the window above a table that doubles as a workbench. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Assorted cacti line the workbench at UNM’s greenhouses. Some of Wes Noe’s notes examing groundwater depth in the Oxbow. (Photos by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

SILE, N.M.—Phoebe Suina, a hydrologist and board member of the Interstate Stream Commission, stands in front of the federally built reservoir on Cochiti Pueblo. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The Rio Grande flows near Albuquerque as the sun rises over the Sandia Mountains. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Phoebe Suina checks the leaves of a young coyote willow and cottonwood saplings along tributaries near Horn Mesa in the Jemez Mountains. She describes her connection to the river as something that is always a part of her, The river is something Phoebe Suina carries with her always. “I look at my hand, and you have all of these veins. They’re all blue, just like a river,” Suina (Cochiti Pueblo) said. “As blood flows through us, so do the rivers and streams across the land from the mountains.” (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The moon sets into a thicket of coyote willow along the Rio Grande. Drought, and a changed river mean salt cedar and other invasive species have muscled out indigenous plants such as the copses of cottonwoods and coyote willow along much of the river’s banks. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Phoebe Suina dips her hands into the Rio Chiquito. Suina said water has to be treated as precious or “we lose what we take for granted.” (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

SOCORRO COUNTY, N.M. — Mallory Boro and Keegan Epping comb through the fine net for any silvery minnows left in the drying ponds of the Rio Grande at San Acacia. Fish litter the riverbed, inhabiting increasingly smaller ponds where the river breaks. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Four team members, left, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service pull on their shoes before a fish rescue. Mallory Boro, Lyle Thomas, Keegan Epping and Thomas Archdeacon often work extended hours in the heat to comb through more than 18 miles of riverbed that can dry nearly overnight. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A vehicle in the dry riverbed of the Rio Grande. The San Acacia Reach is a stretch of the Rio Grande that has dried nearly every year for the past 25 years. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service team pulls seine nets through almost any pool left in the drying riverbed. The rescuers check each pool for silvery minnow. They throw back the other species of fish. The pools are often hot and poorly oxygenated. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Silvery minnow are primarily found in a stretch of the Rio Grande between Cochiti Dam and Elephant Butte — if there’s enough river to support the fish. “If some catastrophic event occurs, they’re a lot more vulnerable because it’s more likely to affect all of them,” said Thomas Archdeacon, left. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Some of the pools range in depth from a few feet to a few inches. Under the June sun, they rapidly shrink. Archdeacon noted that the pools were appearing earlier each year, and the river is drying faster. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Lyle Thomas places a silvery minnow found in a pool into an oxygenated holding tank on the back of the carts. The fish are transported to better environments, but their survival rate is low, since the fish are often unhealthy from being in the pools. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Silvery minnows are placed in an oxygenated tank for transport upstream. Fish who are rescued from pools have a much lower survival rate that fish pulled from running water. Archdeacon estimated there's only a 5% to 10% survival rate for rescued fish. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife team measures the temperatures of each pond, noting what kind of conditions the rescued fish are coming from. At right, Mallory Boro discards a fish from the net, when the pool is too small to return it, searching for silvery minnow. (Photos by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

From left, a gizzard shad in the streambed. At right, fish species of all kinds turn muddy and brown from struggling to find water in the San Acacia reach, dying by the hundreds. (Photos by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Shoals of silvery minnows used to swim nearly 3,000 miles of the Rio Grande’s length from the Gulf of Mexico to Española, N.M., and along much of the Pecos River. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

When rescuers find a silvery minnow, they note its origin (if it's wild or from a hatchery), and what condition the pool was in. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

When the water dries fish gasp for hours in the streambed until they die.(Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

CARNUEL, N.M. — Danzantes, from left to right: LeAnne Chavez with her father Ted Chavez, 6-year-old Deja Tapia and Isaac Nieto for the Saint Anthony Fiesta in June 2022. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Ted and LeAnne Chavez follow other congregants into the church for vespers before the procession. In previous years, the figure of Saint Anthony would be carried up the mountain to a small spring for a blessing, but the combination of drought, heat and health concerns shortened the procession. (Photo by Dianna Cervantes for Source NM)

Deja Tapia, 6, plays the part of la Malinche in the procession. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

LeAnne Chavez adjusts her fathers handkerchief before the procession. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Matachines gather near the Ojito of San Antonio as the priest led everyone in a prayer on June 9, 2018. (Photo by Diana Cervantes)

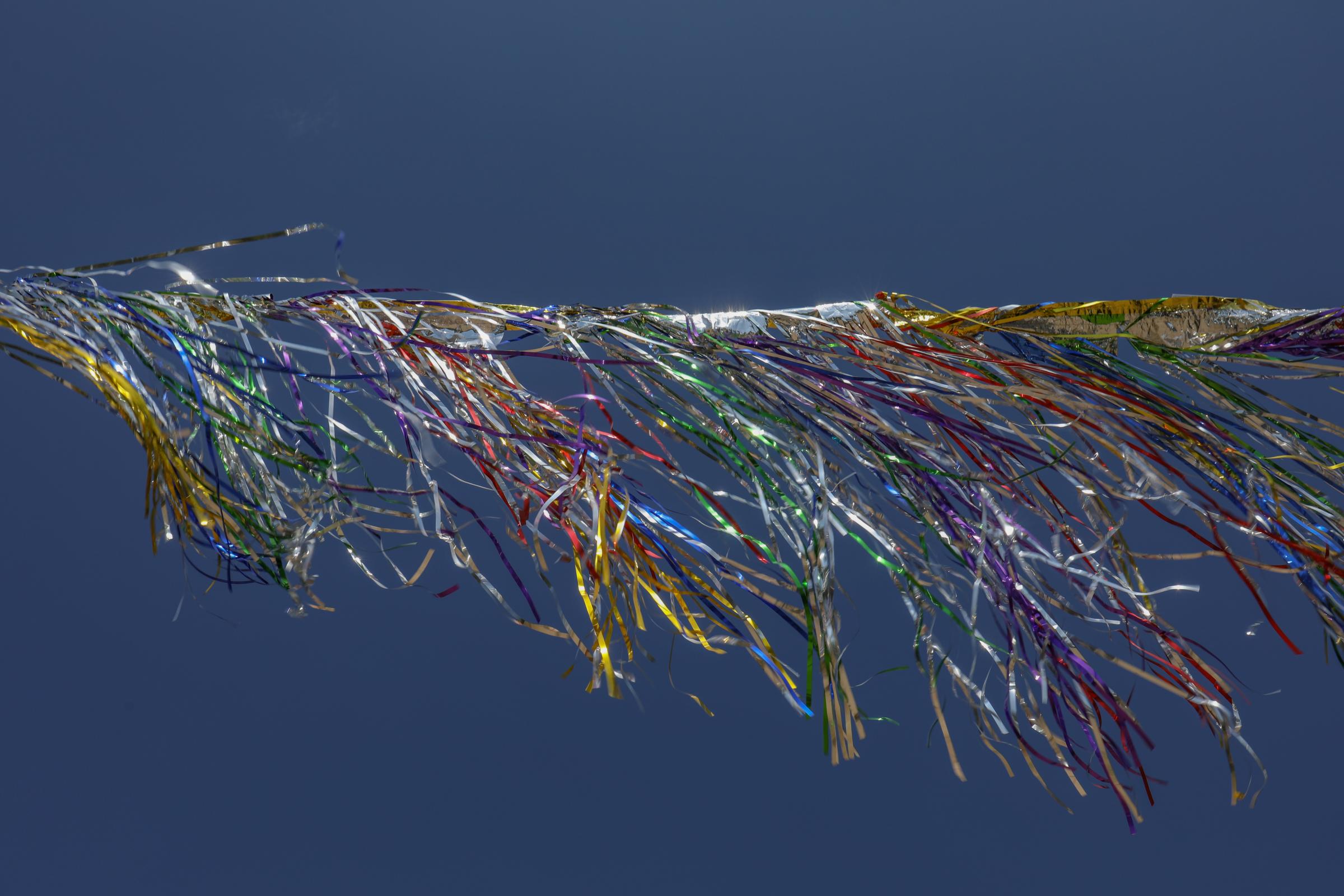

Party streamers glistening in the sun outside of San Antonio Mission Church on June 9, 2018 for the Feast of San Antonio. (Photo by Diana Cervantes)

Rio Grande water released from Caballo Dam on June 1, 2022. The water travels downstream for several days to reach the riverbed running through El Paso, Texas. Releases used to come in March or April, but with less water flowing downstream, managers now wait until nearly the middle of the growing season. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Irrigation water sinks into pecan groves on the Texas-New Mexico border. Farmers in the region have been relying on groundwater pumping to keep crops alive as irrigation water has become increasingly unreliable. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

The Vinton stretch of the Rio Grande just north of El Paso at Vinton Road and Doniphan Drive on May 23, 2022. The river below Elephant Butte Reservoir in Southern New Mexico through Far West Texas is dry most months of the year, only running during irrigation season. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

SOCORRO, TEXAS — Estela Padilla recalls memories of the river from her youth in her home in El Paso, Texas. “What we have managed to do in my lifetime, I don’t think even Mother Nature does that sort of thing in the natural world,” she said. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A Gambel’s quail roo sits atop a tree overlooking the Rio Bosque Park. The changes to the Rio Grande made in the 20th century transformed the landscape, meaning the river has lost as much as 93% of its wetlands habitats. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Estela Padilla on the morning of June 18, 2022, at Bosque Wetlands Park, where she goes to walk. It’s a favorite place of hers. “What they have done here is magic,” she said, pointing to the cottonwoods. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Seepage from Caballo Reservoir fills the river at Percha Dam State Park in New Mexico, allowing for grasslands and a strip of native trees to grow here. Dam construction, flood control and agricultural shifts to the lands upstream from El Paso eliminated the river patterns that allowed cottonwoods and willow bosques to grow downstream. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Estela Padilla stands for a portrait underneath a willow tree at the Rio Bosque Park. Her dream for the river is “that we would find a way to create natural habitats for wildlife and for plants.” (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

John Sproul, manager of the Rio Bosque Park, waters a young willow. nicknamed by some as “the father of the bosque.” Sproul, 73, is soft-spoken. Binoculars around his neck, he stands in the shade of the park he’s dedicated more than 25 years to. “It’s just satisfying to see this area being transformed,” Sproul said. “We’re getting back to something that’s at least approximately what once was found in the valley of this region.(Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Cattails grow in a dry wetland cell at the Rio Bosque Park along the U.S.-Mexico border. Due to high temperatures and drought, the cells cannot remain wet during much of the spring and summer. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

John Sproul and Sergio Samaniego fill buckets from a water bladder the morning of June 17, 2022. Sproul hauls the water to the park in his truck every other morning to water the cottonwood and willow saplings by hand, hoping they survive the harsh heat. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

An old struggling cottonwood at Rio Bosque Wetlands Park, the continuous drought is incredibly hard on all of the trees. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A bed of cottonwood seeds.(Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

John Sproul carries buckets every few feet to water the cottonwoods. In mid-June, when the monsoons finally build up and burst over El Paso, a palpable relief is felt throughout the park. The wet of the earth and petrichor create a heady perfume. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Algae and reeds grow within the shallow pools at Rio Bosque Park. These shallow pools are supplied by a nearby well pumping groundwater. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Sproul is not alone in his work. Assistant Manager Sergio Samaniego now makes it a two-person operation. Plus, a host of volunteers helps clear cattails or plant cottonwoods. “I discovered a magical place,” he said, walking along the wetland cells, dried cattails rattling in the wind, occasionally raising his binoculars to watch for hawks. “Everything is interconnected. I see the importance of water and how rare it is,” Salmaniego said. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Salmaniego and Sproul look out at owls roosting in man made structures built for them throughout the bosque.(Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

A butterfly among some reads in a pool supplied by groundwater from a nearby pump. An oasis for many insects and wildlife. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Rio Bosque Park Manager John Sproul looks through dry cattails for signs of water flowing into the river channel. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

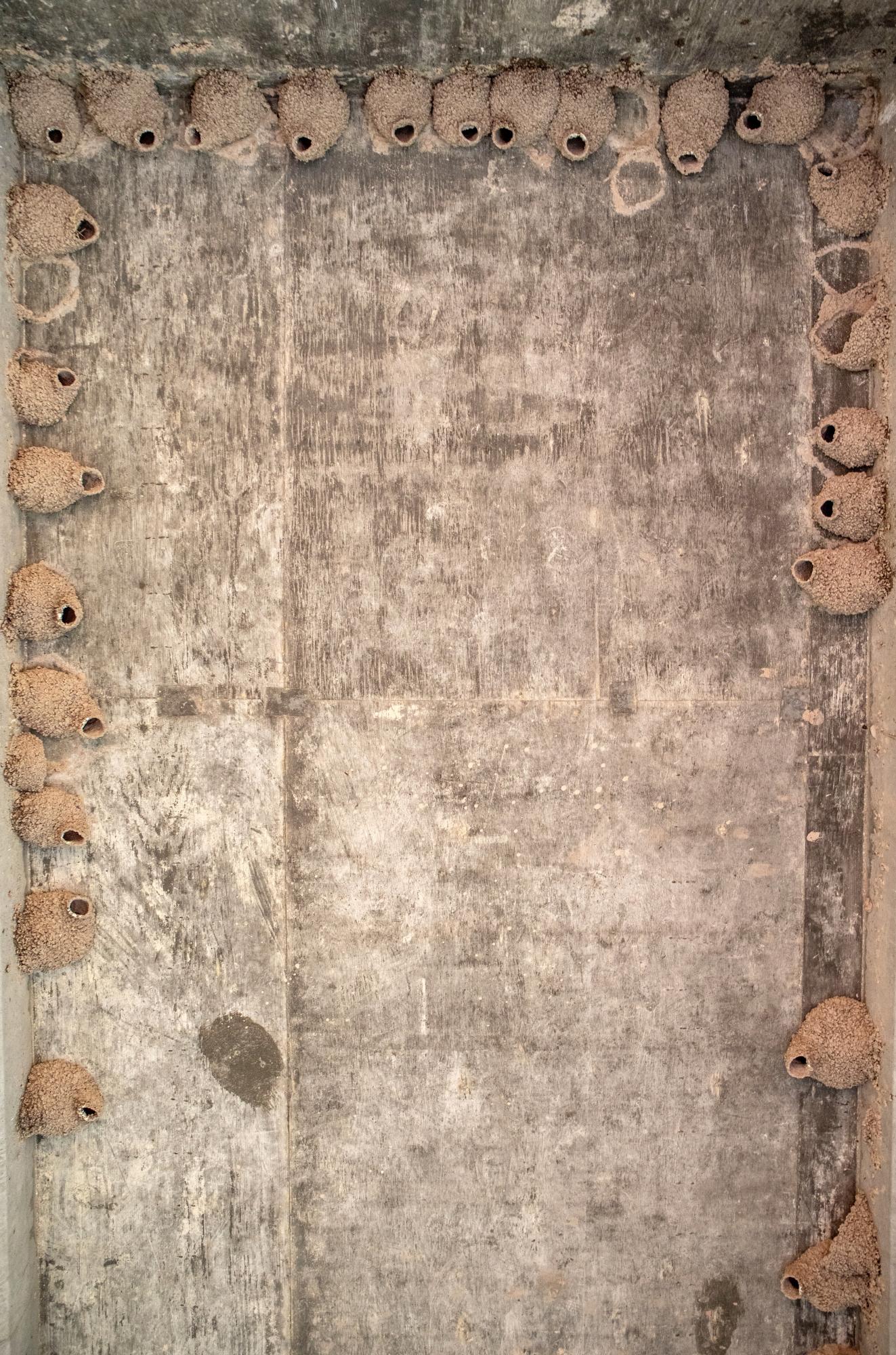

Swifts fly to and from a bridge near the Sunland Park pools to roost for the night in nests they have built out of sediment from around the river. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

White-throated swifts carry insects to feed their young, nestled against the bottom of bridges along the Rio Grande. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Swift nests they have built out of sediment from around the river. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Groundwater pools into the Rio Grande riverbed, offering refuge to black-necked stilts, waterfowl, even a rogue peacock. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Trucks occasionally rumble over the Sunland Park pools, cut by a train horn in the distance. Otherwise, sounds of the city slip away, and the twittering of swallows dominates the pools. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM

A black-necked stilt flying over the shallow pools. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM)

Crisis on the Rio Grande

#Media

Public Project

Crisis on the Rio Grande

Copyright

Diana Cervantes

2025

Date of Work

May 2022 - Feb 2023

Updated Mar 2023

Location

Southwest

Topics

Media

1,298