Ten-year-old Cristina during a training at TKO Youth Boxing Club. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001

Boxing Against Gangs

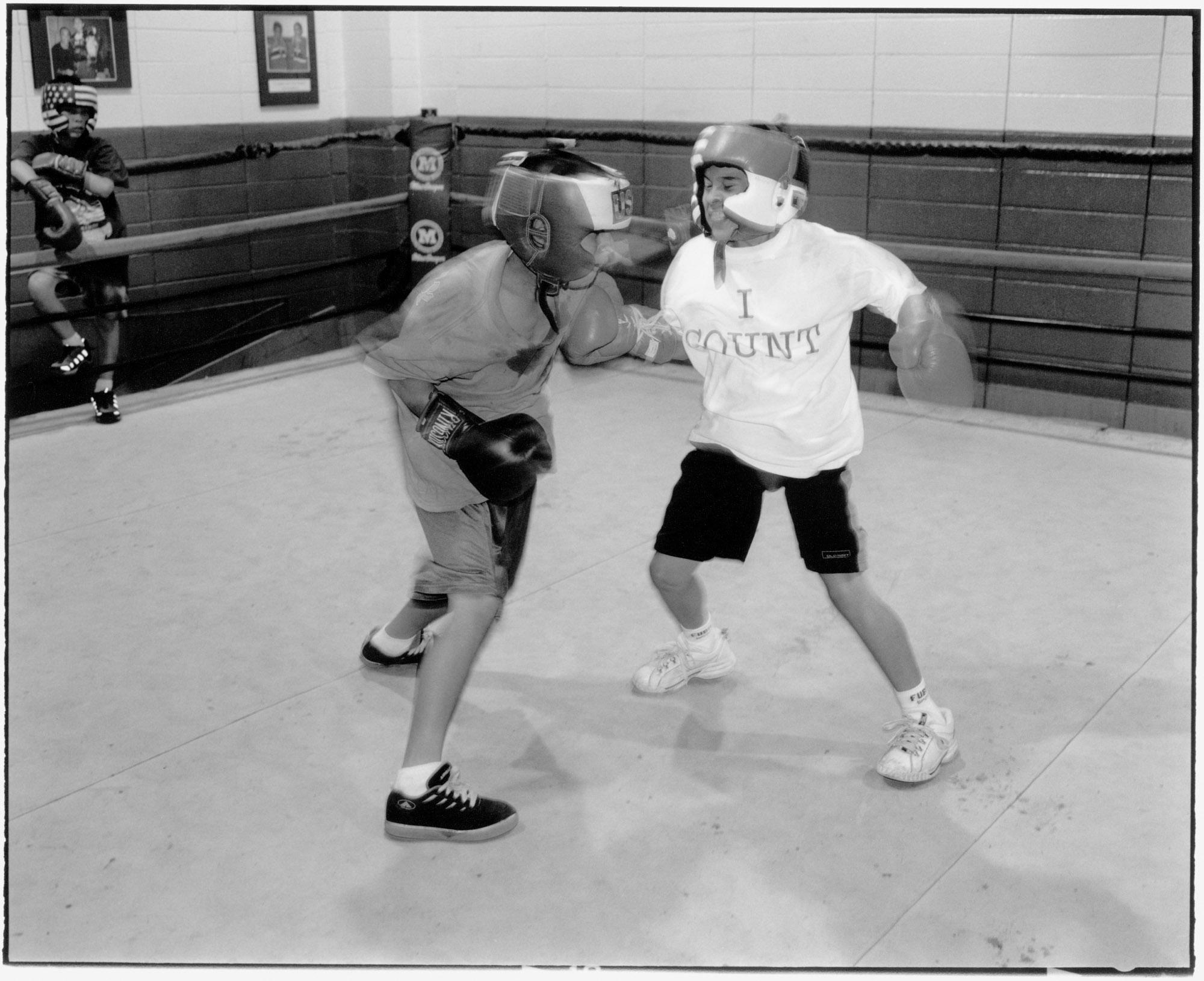

The favorite color of ten-year-old Cristina Ornelas is pink. And of course she sometimes wears a dress. She is a kind-hearted girl, her mother thinks. But this Monday afternoon, with some dull sounding blows of her gloves, she drives her two year older brother Ernesto into the ropes at TKO Youth Boxing Club in Santa Ana. Cristina's nickname at the club is doll, but she is not to be trifled with.

Moments later she is standing puffing in a corner of the boxing ring, her hair spiking from sweat, her mouth still bulging with the plastic tooth protector. Why does she like boxing? "It keeps me in shape", Cristina says. "I've got lots of friends at the boxing school. And I like to fight."

"She has spunk," coach Hector Lopez judges admiringly. "She's very fast. She's definitely one of my better boxers."

Turning Kids On, the club is called in full, TKO also being short for the boxing term technical knock-out. But at this club for children between eight and eighteen the emphasis is on building something up. They want to give the children's self esteem a boost and teach them discipline. They want to instill them with a feeling of solidarity, of friendship. Things that are not always taken for granted in the environment where they are growing up: a working-class area in a suburb of Los Angeles in California, mainly inhabited by Latinos.

Boxing Against Gangs

The favorite color of ten-year-old Cristina Ornelas is pink. And of course she sometimes wears a dress. She is a kind-hearted girl, her mother thinks. But this Monday afternoon, with some dull sounding blows of her gloves, she drives her two year older brother Ernesto into the ropes at TKO Youth Boxing Club in Santa Ana. Cristina's nickname at the club is doll, but she is not to be trifled with.

Moments later she is standing puffing in a corner of the boxing ring, her hair spiking from sweat, her mouth still bulging with the plastic tooth protector. Why does she like boxing? "It keeps me in shape", Cristina says. "I've got lots of friends at the boxing school. And I like to fight."

"She has spunk," coach Hector Lopez judges admiringly. "She's very fast. She's definitely one of my better boxers."

Turning Kids On, the club is called in full, TKO also being short for the boxing term technical knock-out. But at this club for children between eight and eighteen the emphasis is on building something up. They want to give the children's self esteem a boost and teach them discipline. They want to instill them with a feeling of solidarity, of friendship. Things that are not always taken for granted in the environment where they are growing up: a working-class area in a suburb of Los Angeles in California, mainly inhabited by Latinos.

A training afternoon.. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

In the United States boxing is for poor city kids. Their parents cannot afford sports that demand expensive outfits or private lessons. Boxing is affordable and guarantees children from working class neighborhoods the personal attention they frequently lack in school. It is moreover a sport that teaches valuable lessons: that you can win, but also need to learn how to be a good loser. That it is smart to respect others. And the structure, concentration and perseverance that are required for boxing, also affect their school performances. Last but not least, it could get them into the kind of college that would otherwise be way too expensive. Being good at boxing can earn you a scholarship.

No candy and soda

"It's their passion", says Norma Ornelas, the mother of Cristina and Ernesto. "After school they rush to do their homework and then they go training, every afternoon. Of their own accord, I don't have to urge them. And when they get home after training, they're still not done. Then they start sparring in the living room. During game season they also strictly stick to their diet: only healthy food, the usual meals, no candy and soda.

"Boxing is my husband's favorite sport, but I never thought I would be having a boxing daughter.

"Cristina was chubby, so I thought it a good idea she would start exercising. She said no to gymnastics. That's too much of a show, she thought. At first she also didn't want to box: too sweaty. But when Ernesto was having a lesson, she would be there, too, skipping for a while or punching against a boxing ball for a bit. At one point Hector, the coach, personally asked her if he could train her. She was eight at the time and when she started she was one of the first girls of the club.

"Now she even beats boys. Ernesto has a lot of respect for his sister. He will never say: you're just a girl. No, he complains: 'Mom, Cristina hits too hard!’"

In the United States boxing is for poor city kids. Their parents cannot afford sports that demand expensive outfits or private lessons. Boxing is affordable and guarantees children from working class neighborhoods the personal attention they frequently lack in school. It is moreover a sport that teaches valuable lessons: that you can win, but also need to learn how to be a good loser. That it is smart to respect others. And the structure, concentration and perseverance that are required for boxing, also affect their school performances. Last but not least, it could get them into the kind of college that would otherwise be way too expensive. Being good at boxing can earn you a scholarship.

No candy and soda

"It's their passion", says Norma Ornelas, the mother of Cristina and Ernesto. "After school they rush to do their homework and then they go training, every afternoon. Of their own accord, I don't have to urge them. And when they get home after training, they're still not done. Then they start sparring in the living room. During game season they also strictly stick to their diet: only healthy food, the usual meals, no candy and soda.

"Boxing is my husband's favorite sport, but I never thought I would be having a boxing daughter.

"Cristina was chubby, so I thought it a good idea she would start exercising. She said no to gymnastics. That's too much of a show, she thought. At first she also didn't want to box: too sweaty. But when Ernesto was having a lesson, she would be there, too, skipping for a while or punching against a boxing ball for a bit. At one point Hector, the coach, personally asked her if he could train her. She was eight at the time and when she started she was one of the first girls of the club.

"Now she even beats boys. Ernesto has a lot of respect for his sister. He will never say: you're just a girl. No, he complains: 'Mom, Cristina hits too hard!’"

Sparring at TKO. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

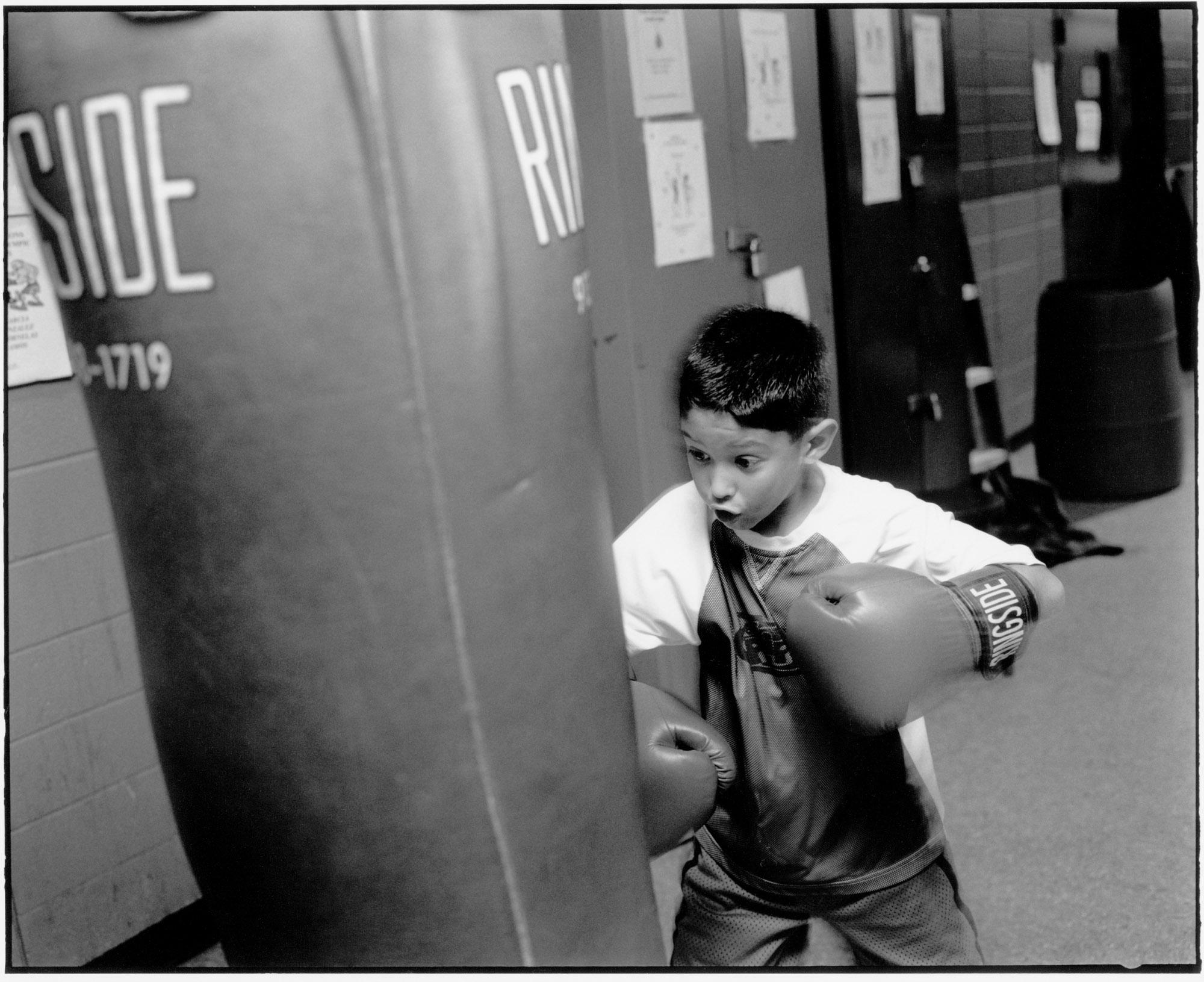

An eight-year-old practices at TKO Boxing School. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

Juliana, 18, Emily, 14, and Cristina, 10, members of TKO Boxing Club, watch other boxers fight in the ring. The girls are waiting for their turn to spar. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

TKO has about fifty members and is still growing. The two coaches do not get paid for their boxing lessons. Hector Lopez has a day job as PR consultant for a pharmaceutical firm. Once he was the manager of several professional boxers, but he never wants to do that again. "Spoiled brats." Now he has a full time job, a wife and an eight-month-old daughter, and trains the kids of Santa Ana five afternoons a week. Every weekend he travels with them to matches in Southern California. The children adore him. They flourish under his attention.

The club was founded in 1994, when Los Angeles and its surrounding suburbs were rocked by the violence of youth gangs. For decades, these have been terrorizing neighborhoods with violence, trafficking in drugs and weapons, burglaries, prostitution and murder. In the past their influence was confined to the big cities. Nowadays there are also youth gangs in smaller cities and even in the countryside.

Hector Lopez says: "We are doing this to keep those young children off the streets. Because of the boxing club they have a goal in their life. Santa Ana is a poor city. This is a bad neighborhood. There are many gangs. These are all very nice kids, but without TKO they still might be temped, out of boredom. Now they are here every afternoon around four o'clock, even the big guys.

"We are getting more and more champions in the group. The children are coming back from championships with titles and trophies. That stimulates the others. When your friend can become a champion, maybe that's in the picture for you as well. And of course they are all dreaming about a professional boxing career. Until now I've had two boys that went elsewhere to do just that."

TKO has about fifty members and is still growing. The two coaches do not get paid for their boxing lessons. Hector Lopez has a day job as PR consultant for a pharmaceutical firm. Once he was the manager of several professional boxers, but he never wants to do that again. "Spoiled brats." Now he has a full time job, a wife and an eight-month-old daughter, and trains the kids of Santa Ana five afternoons a week. Every weekend he travels with them to matches in Southern California. The children adore him. They flourish under his attention.

The club was founded in 1994, when Los Angeles and its surrounding suburbs were rocked by the violence of youth gangs. For decades, these have been terrorizing neighborhoods with violence, trafficking in drugs and weapons, burglaries, prostitution and murder. In the past their influence was confined to the big cities. Nowadays there are also youth gangs in smaller cities and even in the countryside.

Hector Lopez says: "We are doing this to keep those young children off the streets. Because of the boxing club they have a goal in their life. Santa Ana is a poor city. This is a bad neighborhood. There are many gangs. These are all very nice kids, but without TKO they still might be temped, out of boredom. Now they are here every afternoon around four o'clock, even the big guys.

"We are getting more and more champions in the group. The children are coming back from championships with titles and trophies. That stimulates the others. When your friend can become a champion, maybe that's in the picture for you as well. And of course they are all dreaming about a professional boxing career. Until now I've had two boys that went elsewhere to do just that."

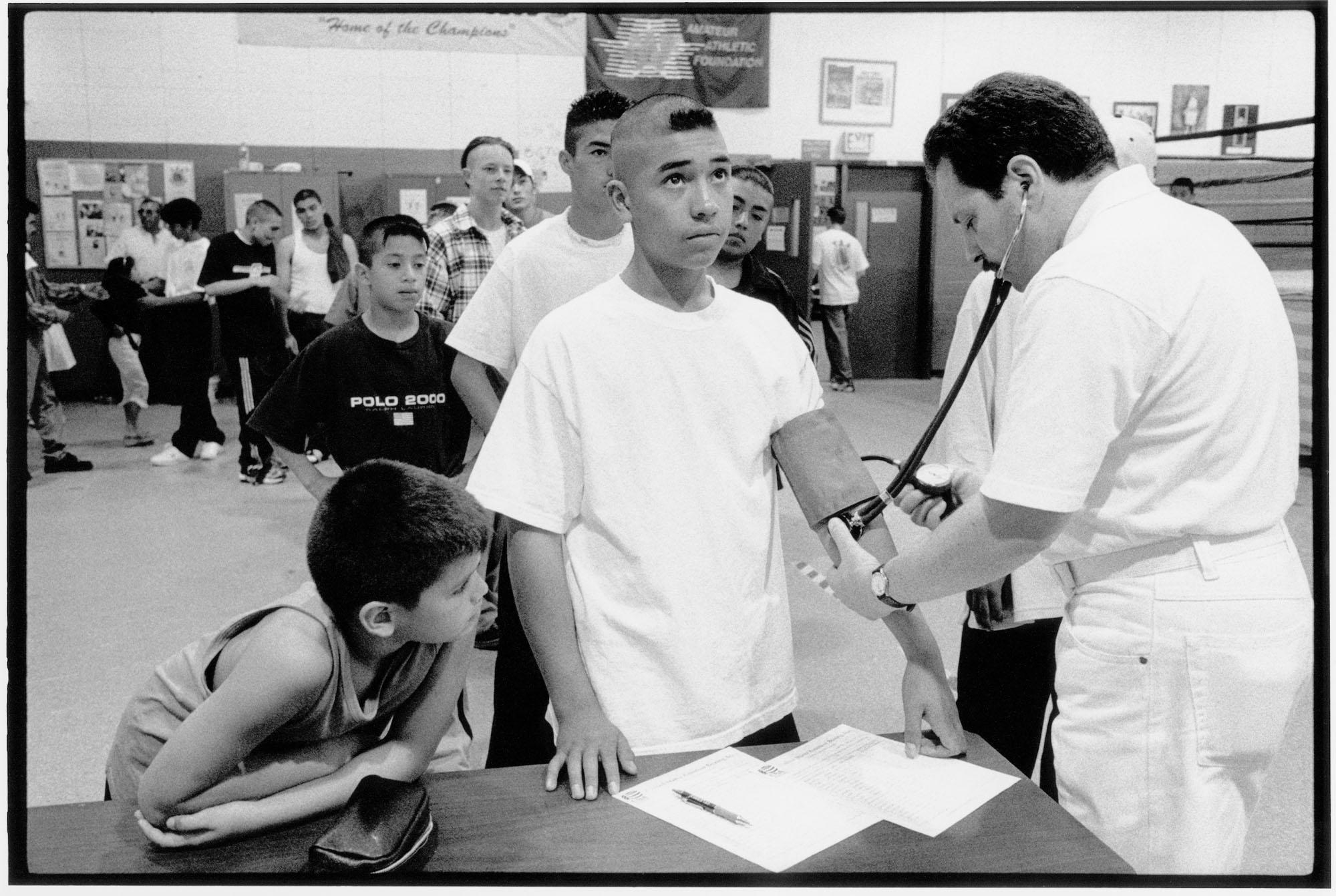

Young boxers undergo a medical check, including the taking of blood pressure, in the gym of the TKO Boxing Club before they are allowed to participate in a tournament that the club organizes. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

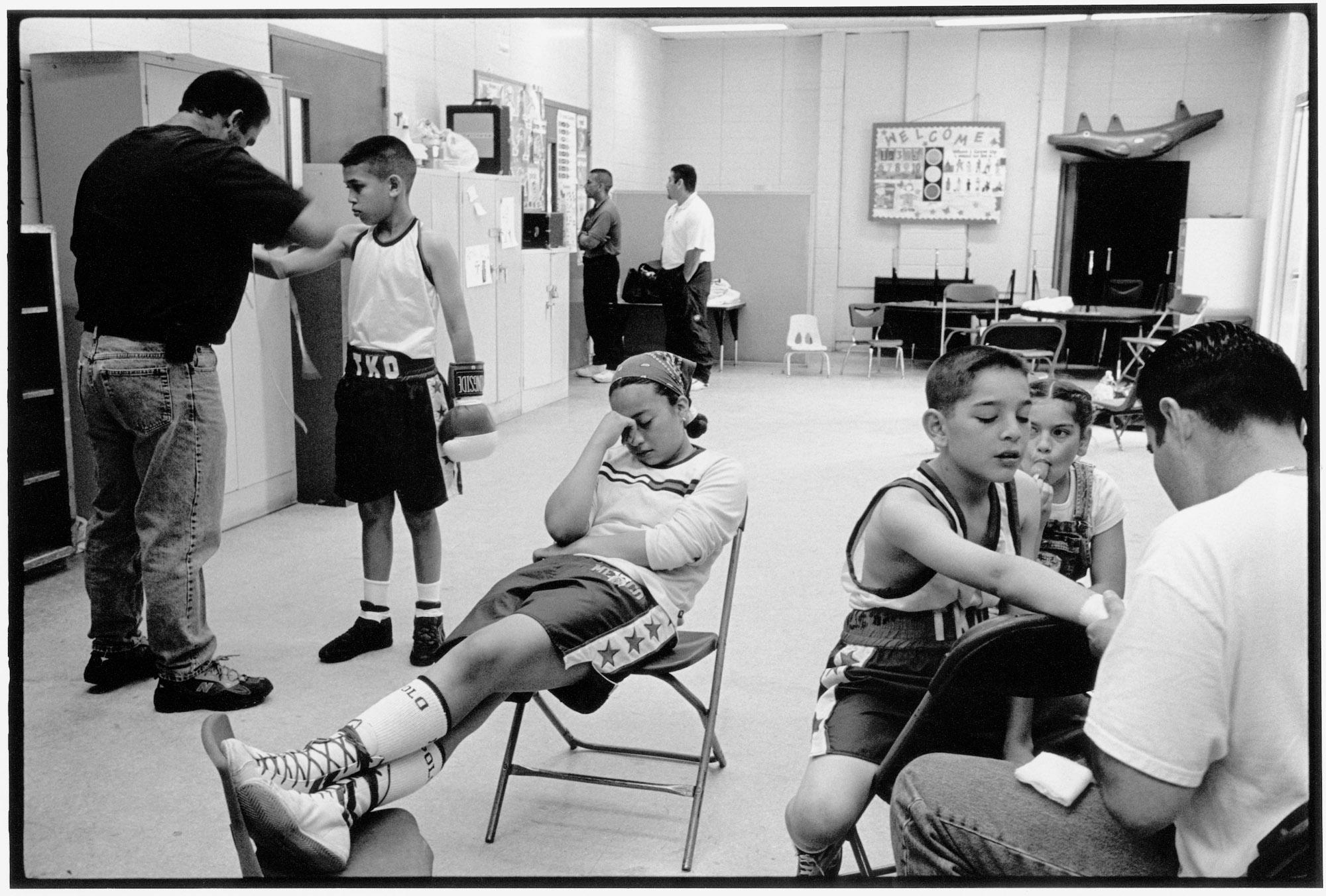

Members of TKO Boxing Club prepare for the tournament their club organizes on a Saturday for young boxers from southern California. In the middle Emily Ramos, 14, prepares herself mentally for het first official match. On the left one of TKO's two coaches ties the glove laces of Emily's brother Max, 12, while on the right coach Hector Lopez wraps Ernest Ornelas’, 12, left hand with protective bandage. Ernesto's sister Cristina sits behind him, eating an ice cream. She is the only one of TKO's youth team not wearing her boxing outfit. She can't take part in a match since no girl her age has shown up to compete against. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

Ernesto Ornelas listens intently to coach Hector Lopez's instructions while waiting for the start of his fight during a boxing competition that the club organizes. The other coach tucks Ernesto's shirt into his waistband to meet regulations, meanwhile keeping an eye on the referee. Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

The boxing club trains in Jerome Gym, an old, dilapidated sports building, that actually is ready to be demolished and hardly can be called hygienic anymore, with blocked, stinking toilets. For matches, the boxers can use the big sporting hall that is the best kept space and that is also used for basketball and gymnastics. For training sessions, TKO shares a smaller space with a group of body builders. Men with prominent muscles are lifting weights, while mothers are helping their children lace big boxing gloves around thin wrists.

The coaches involve the parents in everything that concerns the club. Fathers assist during training, but mothers also keep the boxing bag steady, so their offspring can hit it hard. On the walls next to the boxing ring pictures are hanging of the club champions, as well as handmade posters with the names of winners of recent titles.

Four times a year TKO itself organizes a boxing tournament, that is attended by other clubs from Southern California. Organizing a game is a lot of work, but also a good way to make some money for the cash-strapped club. Spectators pay an entrance fee and eagerly buy the tasty, homemade Mexican food.

Coach Lopez' family also helps out: his wife, sister and mother-in-law sell food, lottery tickets and T-shirts with the logo of the club. The club offers trophies for all the contestants of the twenty fights that can be held during one afternoon.

Lack of competition

On a Saturday in June TKO makes that number easily. They even have to turn down boxers. Cristina is walking around dressed in a bib overall and with a pink ribbon in her braided hair: she can't box today. At the boxing school she fights against boys, but that is not allowed during matches, and no girl of her category has shown up to fight against. It's a common problem, that hampers female boxers in their development, because they miss out on competition experience.

"She's had too much publicity lately," her mother guesses. "That scares other girls and coaches off. They think she's too good, that they can't beat her. But that's nonsense of course."

Cristina has only fought three official contests so far: two wins and one loss. The first time she had to enter the boxing ring for a competition, she was afraid. But not anymore.

Teammate Emily Ramos does have an opponent today: Nancy Hernandez from LA Boxing, 14 years old, just like her. Nancy weighs somewhat less than Emily: 121 pounds against 127, but she already has boxed three competitions and so is the more seasoned one. It is Emily's first match, yet she is not afraid to hit and receive. She bravely strikes away, loudly cheered on by her team. Finally her adversary wins on points. Still, coach Lopez is proud of her: "It was a good experience, she showed excellent willingness."

Cristina's brother Ernesto also has an opponent. In his corner of the ring he listens intently to the instructions of the coach. And a short while later, he beats his opponent, under loud acclaim of his teammates. Yet, coach Lopez is angry: "You were rather slow," he grumbles. "Did you go to bed late? Why? You know you have to go and sleep early if you're having a competition the next morning."

The boxing club trains in Jerome Gym, an old, dilapidated sports building, that actually is ready to be demolished and hardly can be called hygienic anymore, with blocked, stinking toilets. For matches, the boxers can use the big sporting hall that is the best kept space and that is also used for basketball and gymnastics. For training sessions, TKO shares a smaller space with a group of body builders. Men with prominent muscles are lifting weights, while mothers are helping their children lace big boxing gloves around thin wrists.

The coaches involve the parents in everything that concerns the club. Fathers assist during training, but mothers also keep the boxing bag steady, so their offspring can hit it hard. On the walls next to the boxing ring pictures are hanging of the club champions, as well as handmade posters with the names of winners of recent titles.

Four times a year TKO itself organizes a boxing tournament, that is attended by other clubs from Southern California. Organizing a game is a lot of work, but also a good way to make some money for the cash-strapped club. Spectators pay an entrance fee and eagerly buy the tasty, homemade Mexican food.

Coach Lopez' family also helps out: his wife, sister and mother-in-law sell food, lottery tickets and T-shirts with the logo of the club. The club offers trophies for all the contestants of the twenty fights that can be held during one afternoon.

Lack of competition

On a Saturday in June TKO makes that number easily. They even have to turn down boxers. Cristina is walking around dressed in a bib overall and with a pink ribbon in her braided hair: she can't box today. At the boxing school she fights against boys, but that is not allowed during matches, and no girl of her category has shown up to fight against. It's a common problem, that hampers female boxers in their development, because they miss out on competition experience.

"She's had too much publicity lately," her mother guesses. "That scares other girls and coaches off. They think she's too good, that they can't beat her. But that's nonsense of course."

Cristina has only fought three official contests so far: two wins and one loss. The first time she had to enter the boxing ring for a competition, she was afraid. But not anymore.

Teammate Emily Ramos does have an opponent today: Nancy Hernandez from LA Boxing, 14 years old, just like her. Nancy weighs somewhat less than Emily: 121 pounds against 127, but she already has boxed three competitions and so is the more seasoned one. It is Emily's first match, yet she is not afraid to hit and receive. She bravely strikes away, loudly cheered on by her team. Finally her adversary wins on points. Still, coach Lopez is proud of her: "It was a good experience, she showed excellent willingness."

Cristina's brother Ernesto also has an opponent. In his corner of the ring he listens intently to the instructions of the coach. And a short while later, he beats his opponent, under loud acclaim of his teammates. Yet, coach Lopez is angry: "You were rather slow," he grumbles. "Did you go to bed late? Why? You know you have to go and sleep early if you're having a competition the next morning."

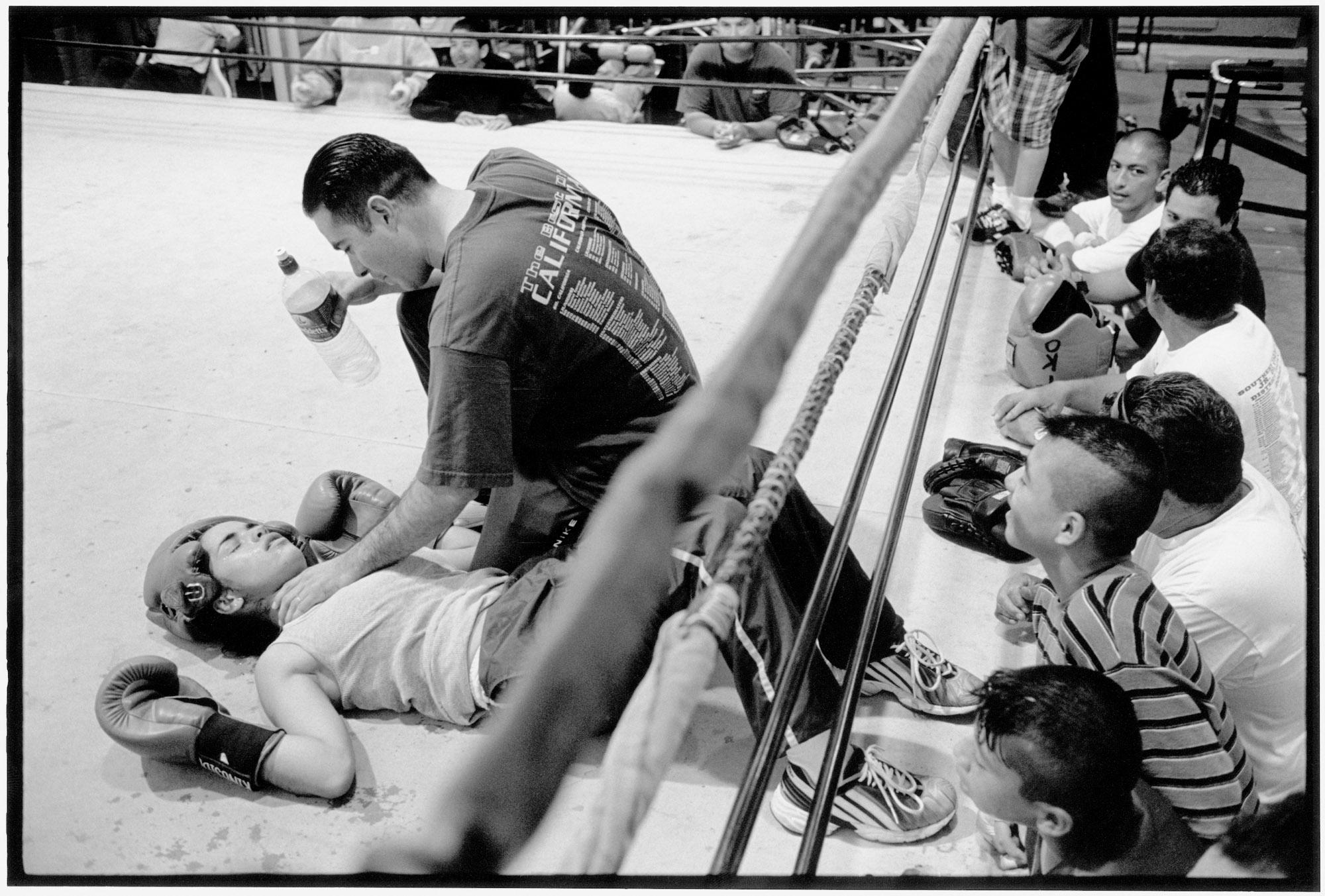

During a game of sparring in the ring of TKO Boxing Club, Juliana,18, has been knocked out by her opponent Emily, 14. Coach Hector Lopez revives the girl by talking to her and by cooling her with a bottle of water.

Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

Santa Ana, California, USA. June 2001.

Public Project

Boxing Against Gangs

3,322