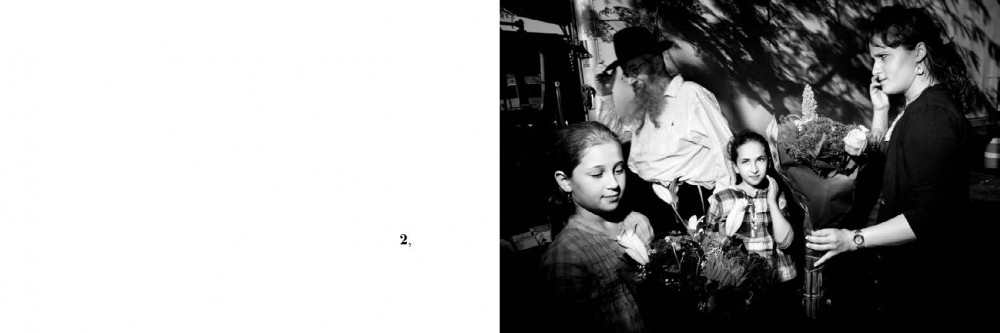

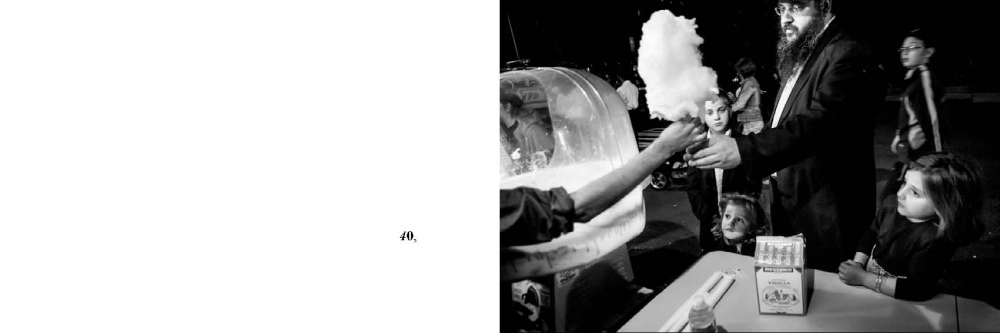

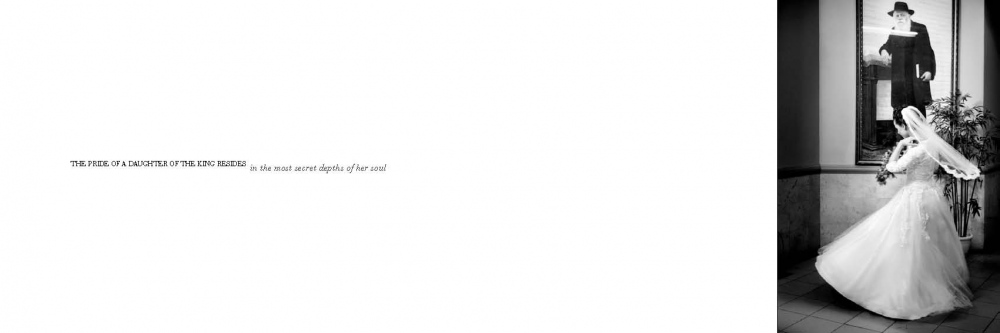

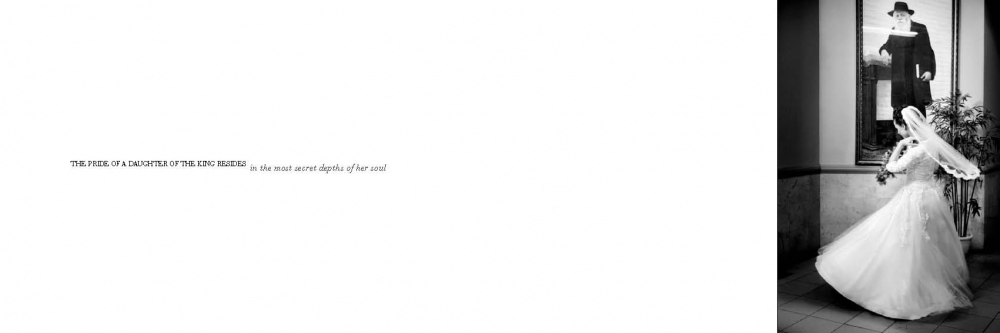

Almost four years ago, I was invited for Shabbat dinner at the Garelik family in Crown Heights, a Lubavitch, Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn. I had just sat down at the table when Rabbi Yossi's wife, Chani Garelik, took me aside and uttered to me a sentence straight from the Torah, "Col Cvuda Bat Melech Pnima," which, translated, means "The pride of a Daughter of the King resides in the most secret depths of her soul." She said to me that if I really wanted my photographs to speak about religious women, I first needed to understand this concept on my own.

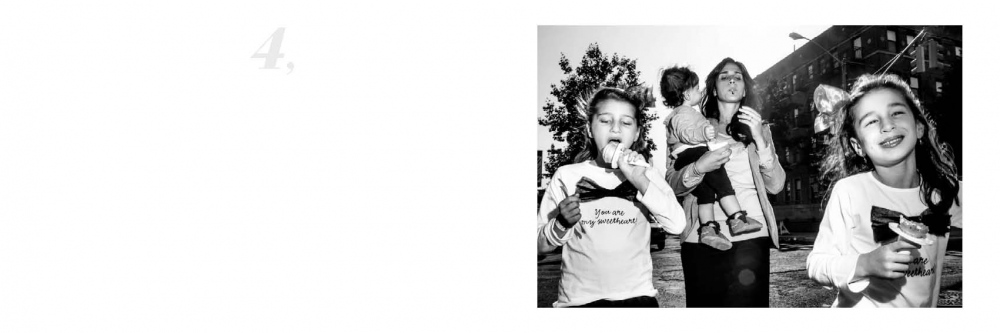

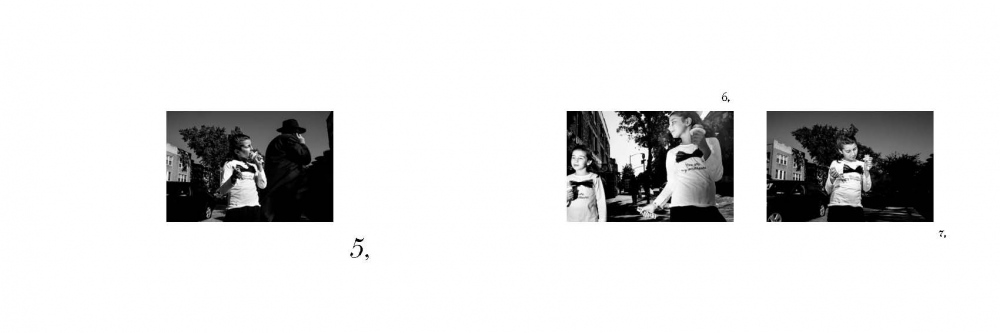

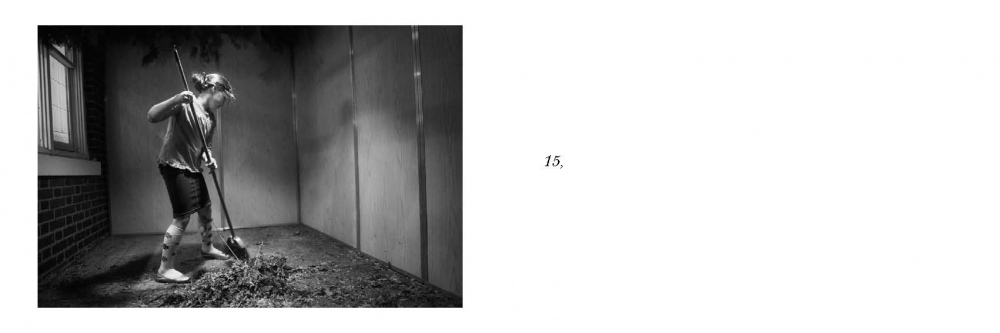

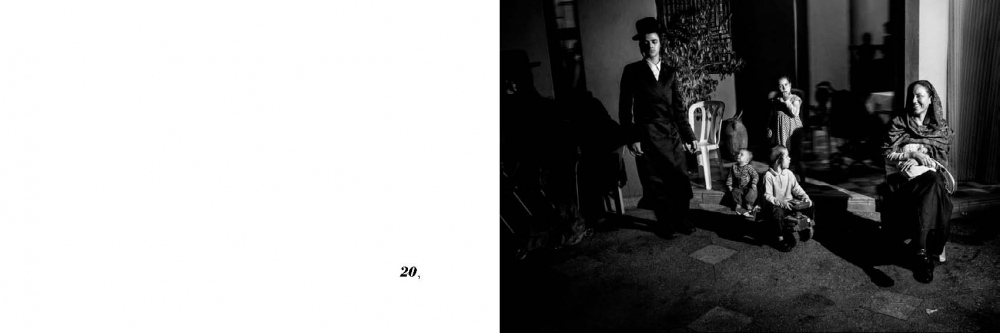

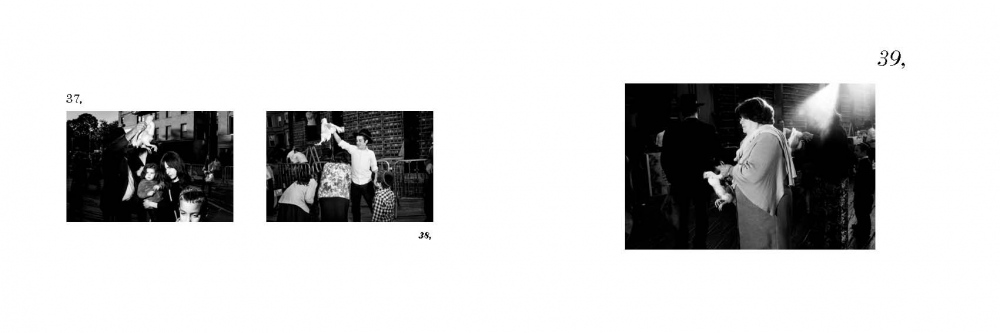

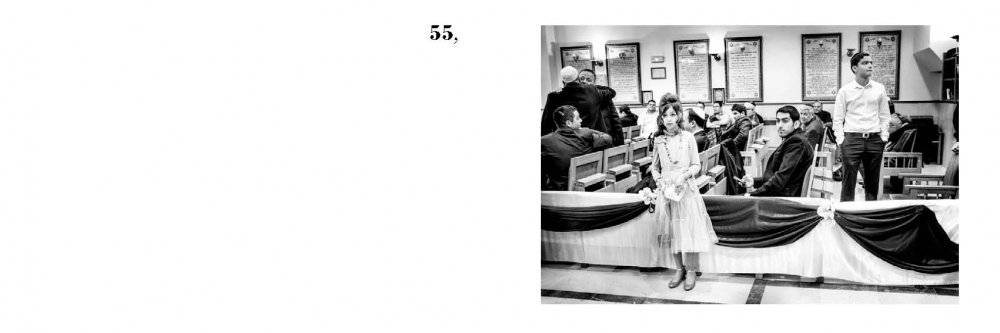

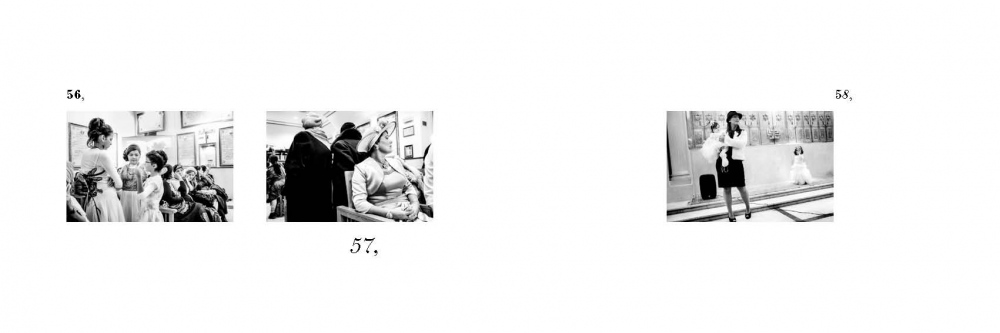

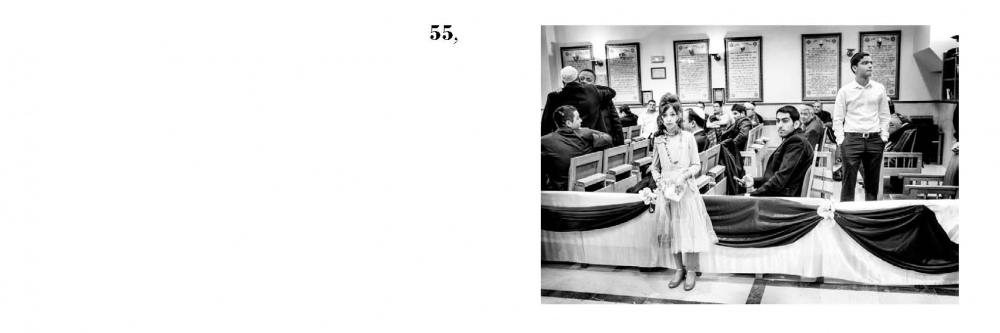

"Daughters of the King" began that night, at that instant, although I was not able to take any photos then. Chani Garelik became my mentor, my so-called Muse. Interestingly, she never permitted me to photograph her. I kept going back to her house to seek advice on how to approach my subjects; how to behave among religious, Jewish women. Little-by-little, I became part of the lives of these women whom I randomly met on the streets of Brooklyn. After a while, they began inviting me to their weddings and dinners. Even now, they recognize me when I am walking in their neighborhood to go shopping, as if I have become part of their world, as if"at least for a moment--I am one of them.

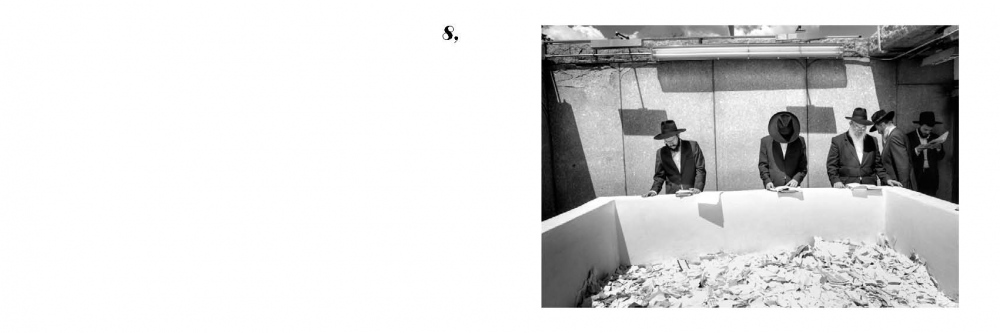

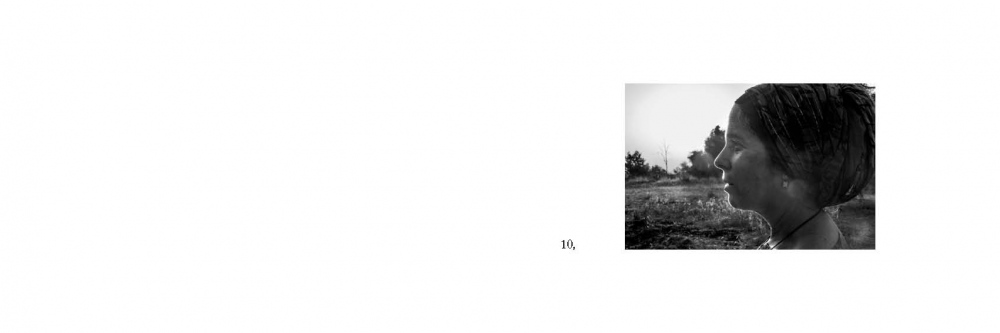

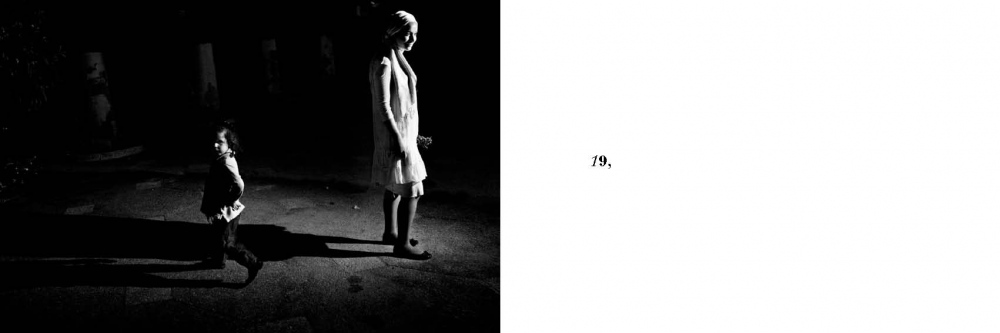

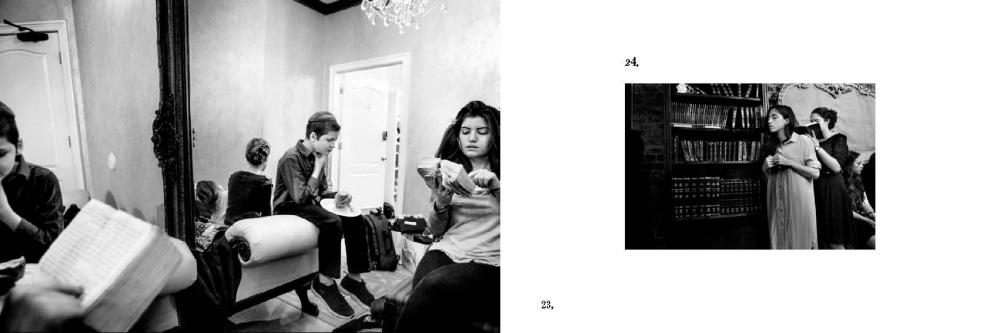

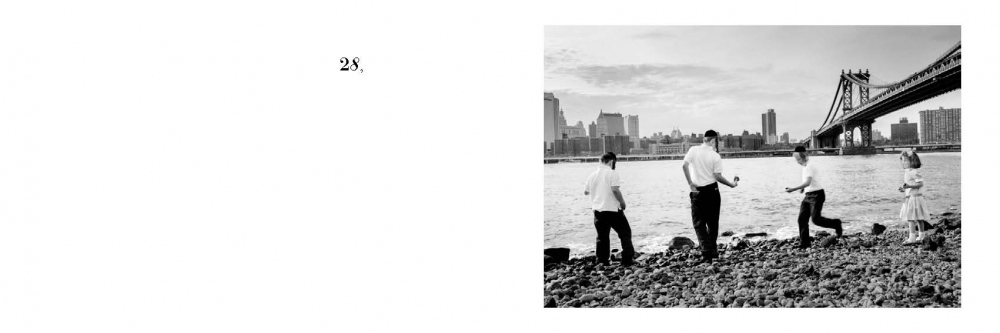

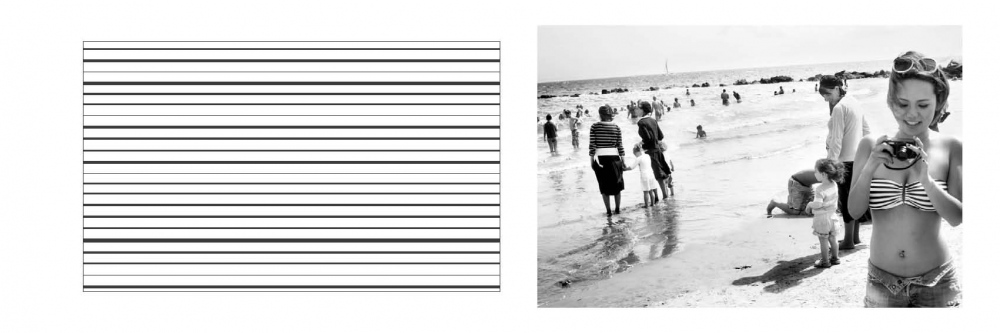

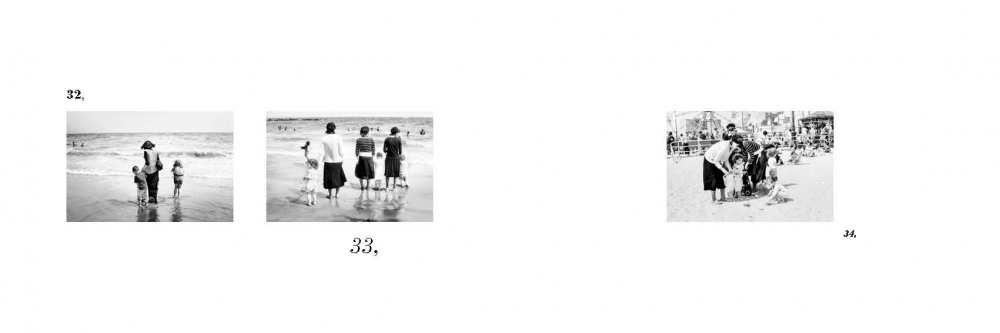

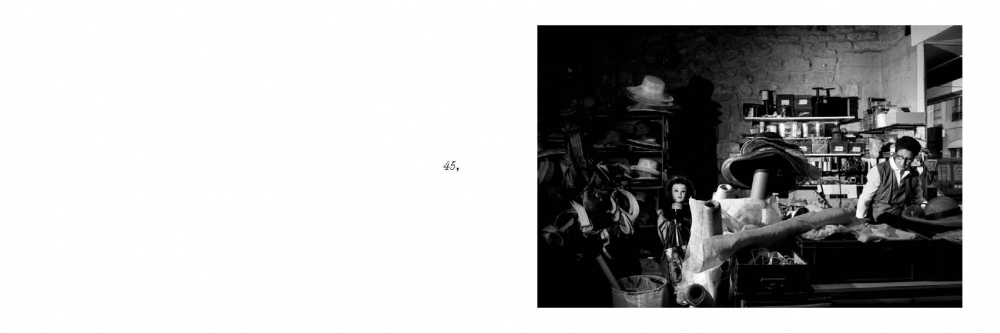

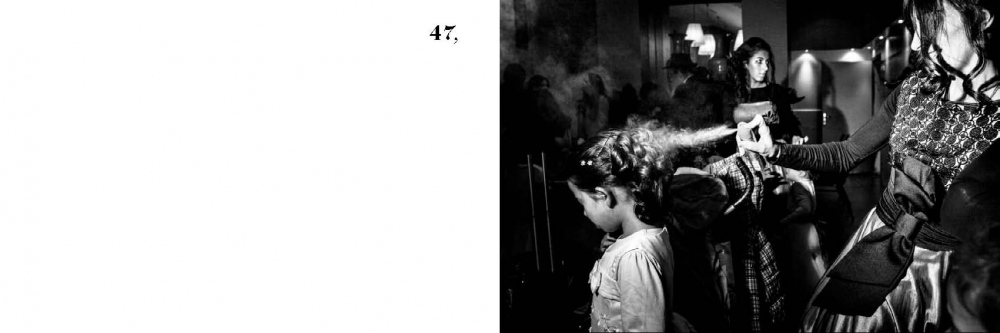

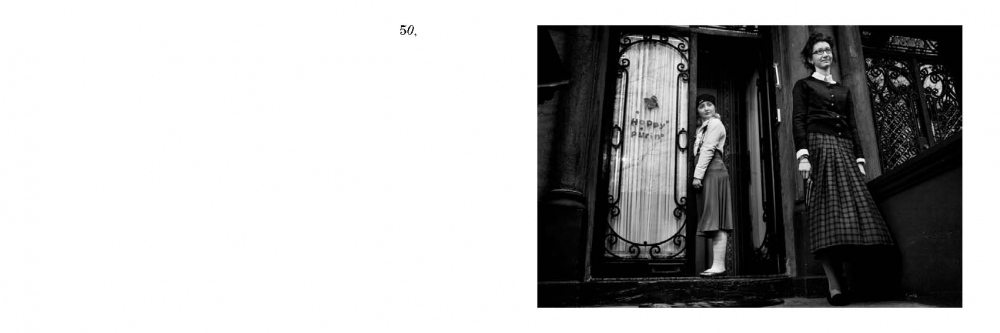

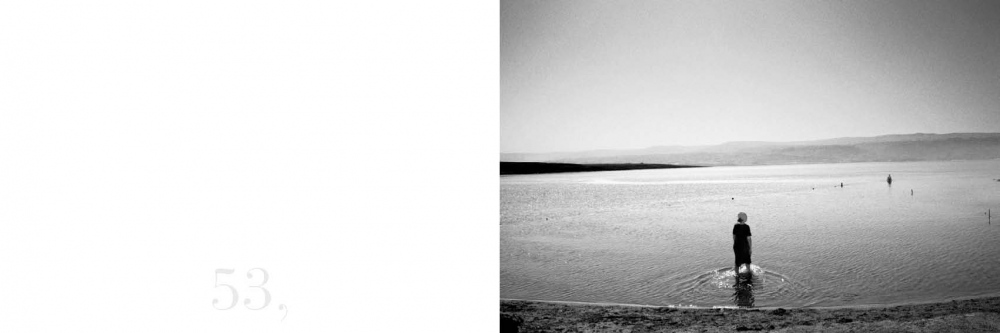

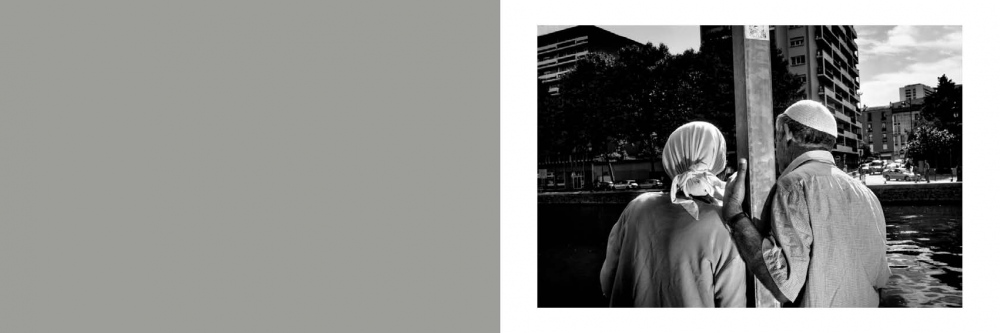

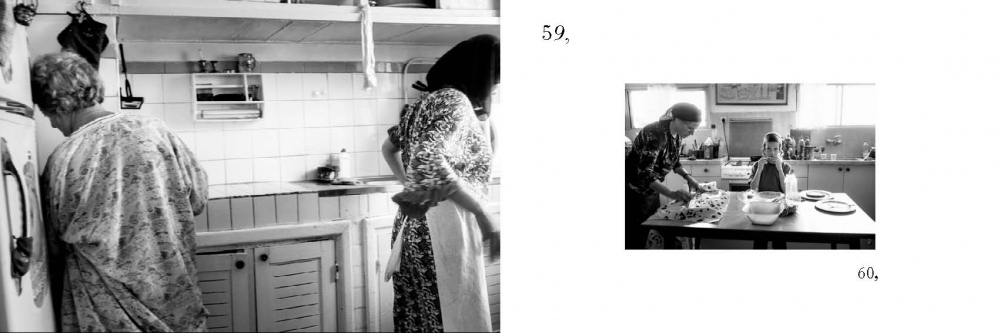

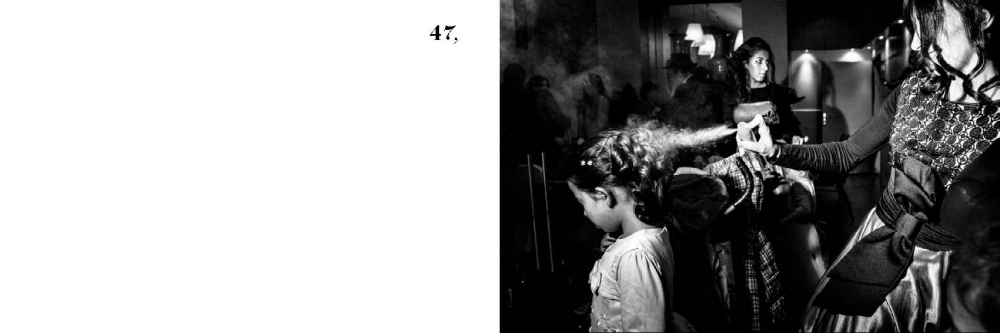

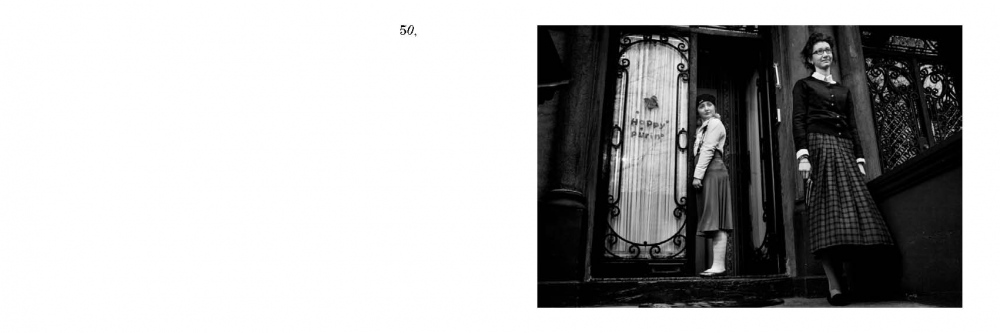

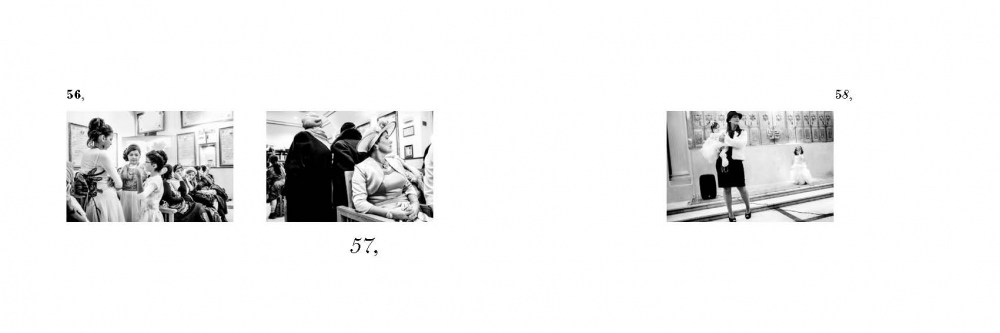

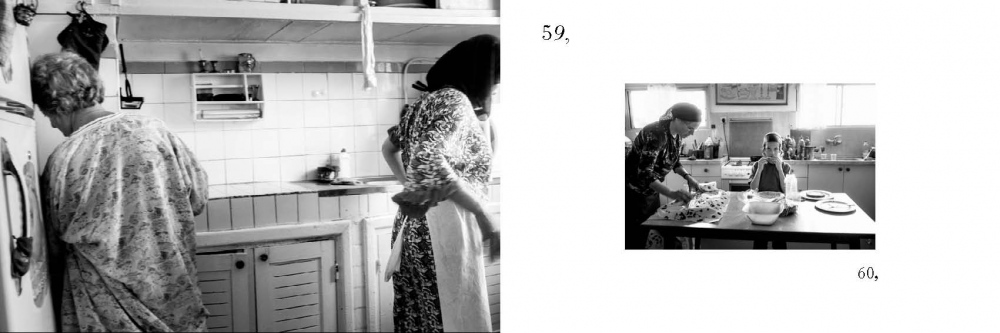

With my photos I have sought to avoid the common stereotypes frequently attributed to Orthodox Jews. I have attempted to show aspects of these women, their most spiritual ones--those that transcend their religion and its strict rules governing the sanctity of their bodies. I chose to delve into a deeper dimension of my subjects' holiness--one of femininity accompanying every gesture, every moment of their daily lives as religious women. In my images, head coverings, long-sleeved dresses, modest skirts and shoes ceased to be barriers to unwanted eyes, but instead, became vessels exalting the attributes of these women, not only as Jews, but simply as women. I chose black and white photography because I believe the monochromatic tones infuse the images with an overall, similar feel, so as to transmit a homogeneous atmosphere, despite the geographic diversity of the women represented. This photography achieves a clear observation, deep into the layers of its image, emphasizing the Orthodox women's charisma and the many tiers and intricacies of their personalities.

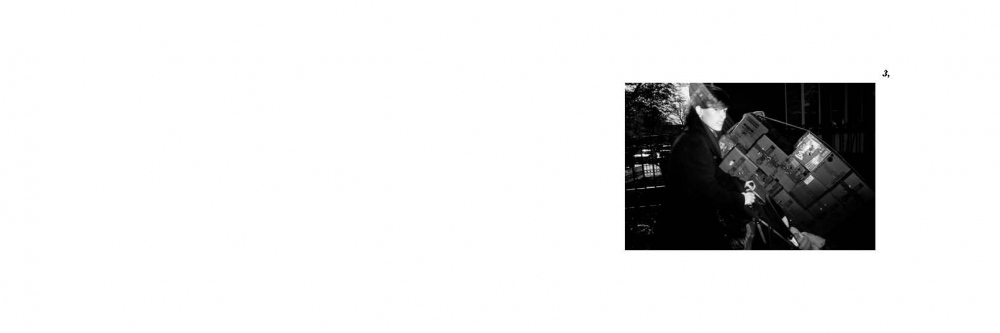

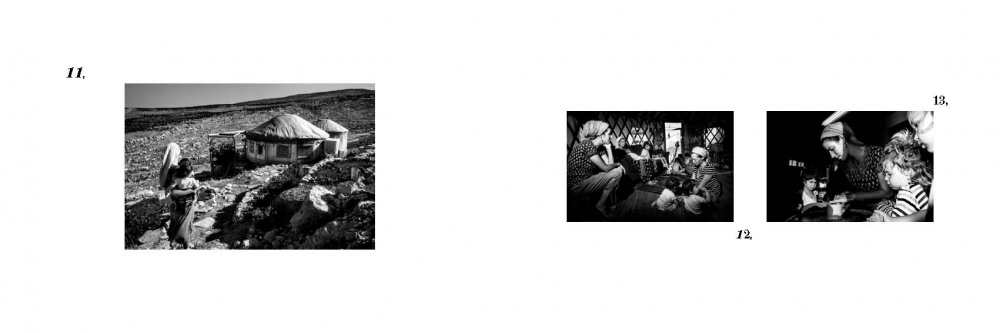

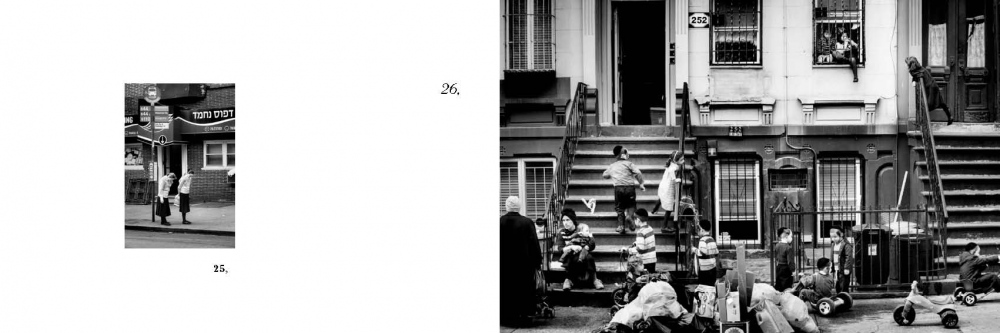

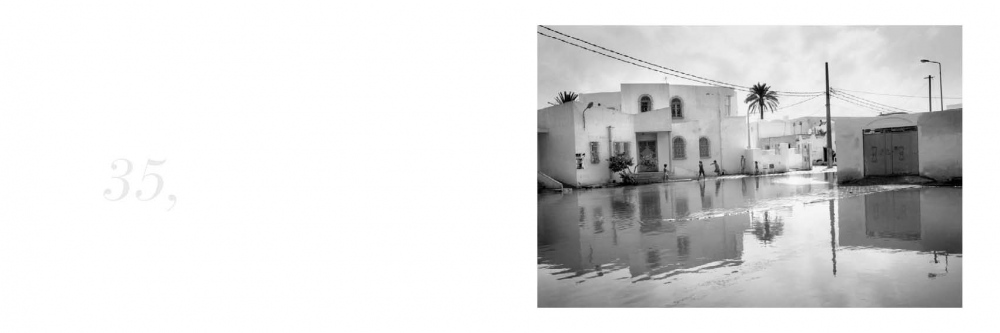

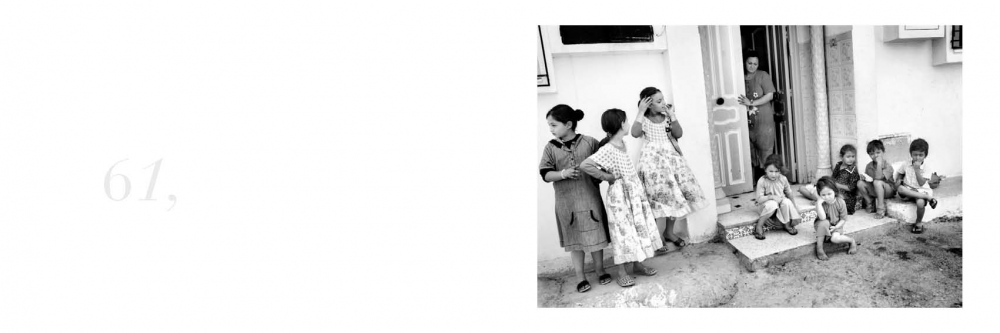

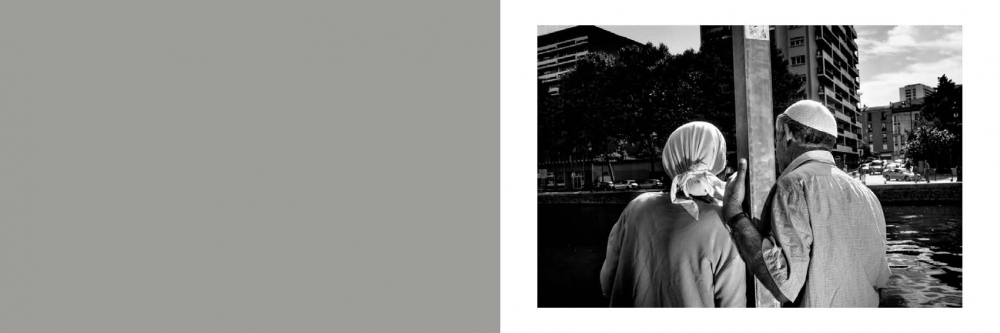

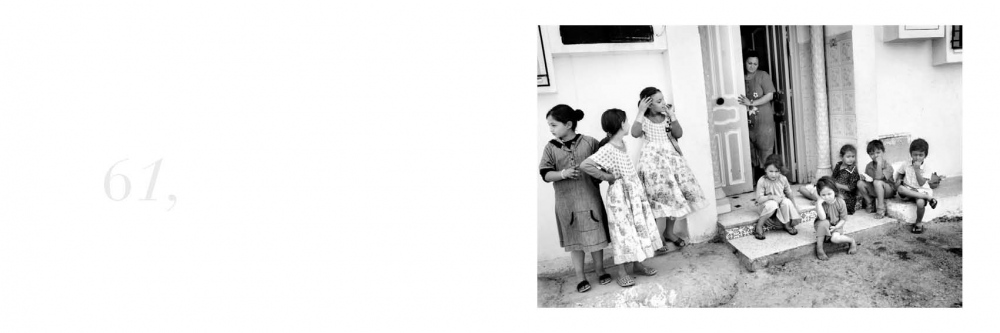

In almost four years, I mainly photographed Jewish women in the largest religious communities in the world: Brooklyn in New York, Israel, and Paris in France. In these countries, the majority of Jews are Ashkenazi, ethnically from northeastern European countries, such as Russia, Poland, and Ukraine. But, since I wanted my photos to show more geographical and historical diversity, I also included Sephardi Jews. So, during this last year, I traveled to North Africa where I took my camera to Tunisia and Morocco. The little island of Djerba in Tunisia is the oldest Sephardic, Jewish community in the Maghreb, one that, even now, maintains a very good relationship with its past colonial power, France.

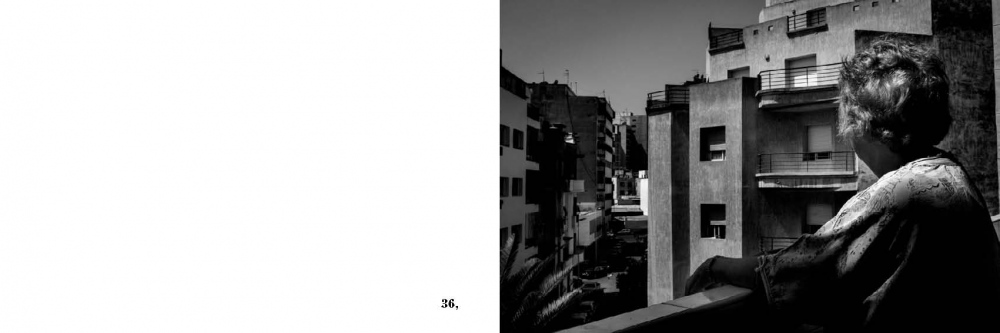

I later traveled to Casablanca, Fez, Essouira and Marrakesh in Morocco, where I was able to photograph the older generation of Moroccan Jews who remained there after heavy migration of the younger generation to Europe. My experience within these communities has not always being easy. Initially, I felt as if these women were interested in pushing their religious ideals on my own secular beliefs. They believed I had come to their communities only to find a Bashert, my soul mate; so, their persistence in wanting me to find someone to marry became a daily obstacle to my photography.

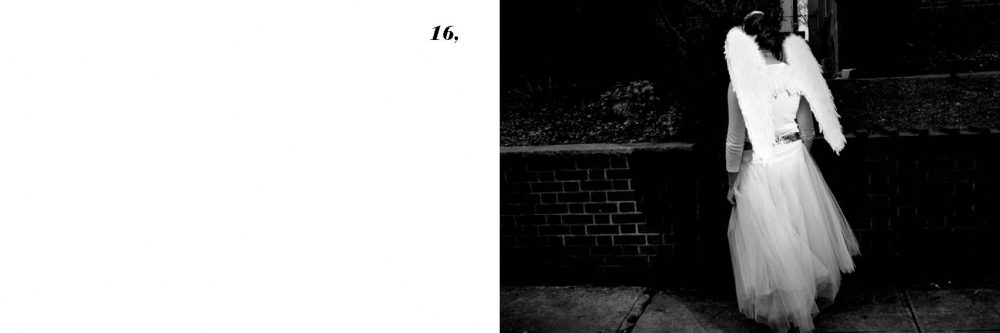

Fortunately, once they understood I was not interested in marrying into their Orthodox community, but that my objective was to explore a world of which I was ignorant and wished to explain to outsiders, who, for years, hadpointed at it with disbelief and judgment.As a non-religious Jew born and raised in a non-Orthodox community, I was very curious to discover whethersome of these orthodox women questioned if it is at least possible for them to reconcile modern views about the role of women in our society with the traditional, orthodox view concerning the role of women in their society.

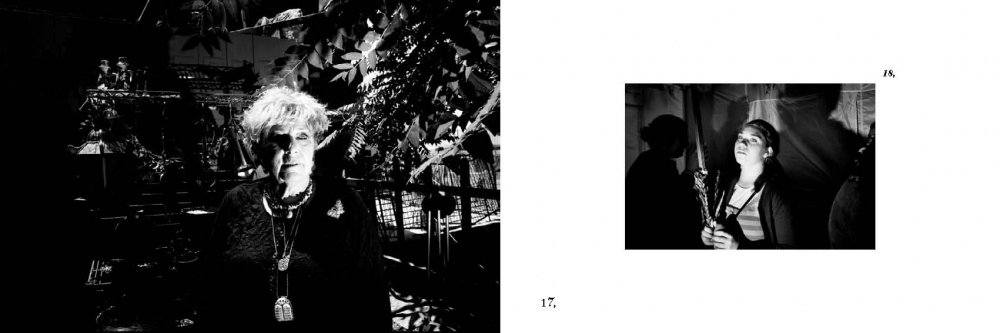

With time passing, these religious women changed their attitude toward me, and started showing me my own way inside the Torah without pushing me any further toward their own religious views. Without knowing me, these orthodox women offered me their friendship, their companionship, and their support"accompanying me on a four-year journey that helped me redefine my own confused identity; a woman born of a non-Jewish mother, I was converted at birth to Judaism.

These women took me by their hands and nourished my Neshama, my Jewish soul, with their daily acceptance, enabling me to compare my doubts and insecurities with their Orthodox beliefs concerning a religion that belonged to me only partially by birth. These women "˜lent me their stories' and have shown me a path toward my own version of a Bat Melech, one that had been hidden in the most secret depths of my soul for a long time.