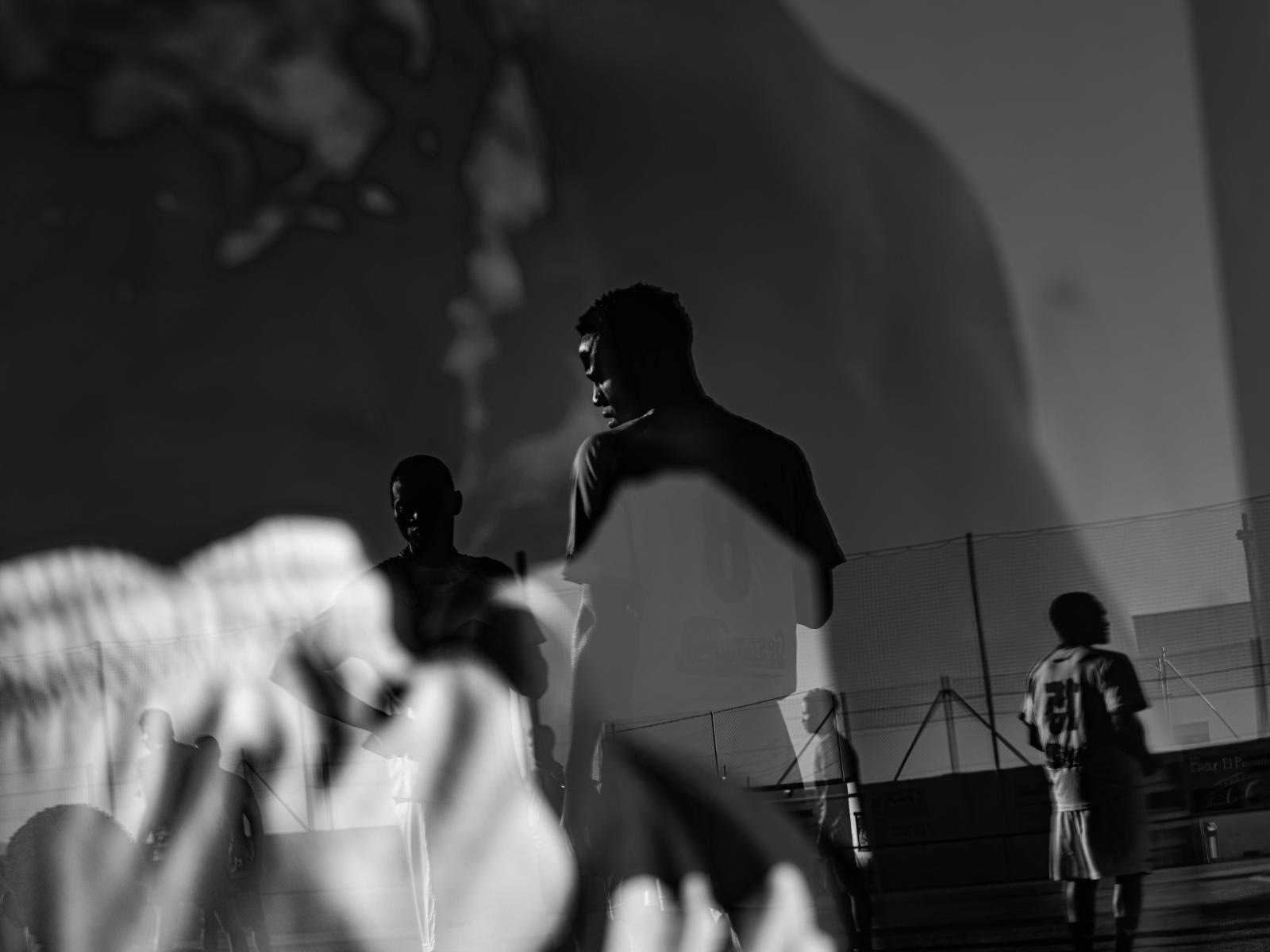

A small group of young Senegalese boys pray near the stadium. The sun sets, and Famara lies on a small mat on the asphalt. Four large spotlights illuminate the grass of the stadium of Roquetas de Mar. A blue grandstand stands to the west, and only a few people occupy its sun-bleached seats covered in dust. In the locker room, twenty boys are getting dressed in green. Famara applauds in the tunnel as his players take the field. Famara is this young Senegalese team's chairman, coach, and sometimes central defender.

The young footballers speak in Wolof, their mother tongue, and represent Cuevas del Almanzora, their Andalusian home. Tonight, they face their countrymen from Roquetas, another southeastern town. Some players, particularly recent arrivals, have yet to understand Spanish despite working in Spain's fields and greenhouses.

Tonight's match takes place on a different kind of field—one of synthetic turf, mirroring the ubiquitous plastic material that drapes over the province. Like a silver mantle, it covers an extension of forty thousand football fields; it's visible even from outer space. As the last daylight fades, the sun sets behind a bright horizon of greenhouses, which seems to engender a glow that illuminates this corner of Spain.

The match kicks off at a blistering pace. Players sprint and vault, cleats kicking up sprays of artificial turf. For a moment, only Famara's orders can be heard, shouting from the sidelines, the intensity of the game increases in the last minutes. A decisive header tilts the score to two-one in favor of Famara's team. The final whistle provokes a burst of contained joy; though rivals on the pitch, the players are bound by a shared journey across the Mediterranean, each risking much to reach Southeastern soil.

The farewell summons a shared laughter, taking photographs as a memento. It is ten o'clock, and there is no time for a shower. Every faucet in the changing room bears a plea for water conservation. Spain's southeast is the driest region in Europe and the nexus of the world's largest agro-industrial complex. Within this hub, seven out of ten workers are migrants, their destinies entwined with the arid landscape and their aspirations.

The players drive back to Cuevas del Almanzora, situated in the eastern province of Almeria. At sunrise, they wake up and go to work or school. The region feels like a desert in broad daylight, a wasteland populated by wild palm trees. Recent storms have torn countless plastic sheets from greenhouses, ensnaring several trees. Patches of green disrupt the rural fringes and flood the cortijos' farmland. The hunting grounds extend through the olive groves that reach the foot of the Betic mountains, etched by the wind and the rain.

Cuevas del Almanzora comes from its ancient caves and the nearby Almanzora River. Its people are humble, and its climate is warm, even in winter. One out of three inhabitants was born abroad, predominantly from Morocco and Senegal. Many African migrants have made their home in the historic town encircling the Church of Encarnación, where once a mosque stood until its demolition in the eighteenth century. The streets are narrow, with old, stately facades and cobblestone roads. Some residences, abandoned and on the brink of ruin, punctuate the streets. Stray cats invade the empty plots. One of the plots now hosts a bush of oleanders.

In 2006, at just twenty years old, Famara took a leap of faith, risking his life to cross the strait separating Morocco from Spain. His journey, encapsulated in the succinct words, "a small boat and many hours," spanned nine days, starting from Casamance in southern Senegal. He fondly reminisces the fleeting time spent in Madrid, at his father-in-law's apartment, forming a deeper bond with his wife, and the hard-earned days working in the fields of the Meseta. Yet the constant surveillance in Madrid drove him to leave, and on June 13th, 2007, he moved to Cuevas del Almanzora, where it was easier to find a job as an undocumented migrant.

Fast-forward sixteen years, and Famara's life has undergone a profound transformation. Today, he shares a modern apartment and a private parking space for his hybrid car with his wife, children, and younger brother, a stark contrast from the early days when he shared a flat with his friend Bassir on the outskirts of town. Now, colleagues Famara and Bassir work as gardeners around Levante Almeriense, managing a standard of living that remains elusive in their native Senegal.

"When I arrived in Cuevas, the Senegalese were already getting together to play," Famara recalls the boys setting up matches in the summer of 2007. As time passed, they gathered resources: balls, socks, and water bottles, eventually securing sponsorship from a local agricultural company that funded their first uniform. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) logo adorns their crest, while the words 'Cultural and Social Sports Association of African Immigrants of Cuevas del Almanzora' stretch across the front of their jersey. "Even though we are mostly Senegalese, we also have members from Guinea, Gambia... hence we chose the ECOWAS shield, representing all of us," explains Famara, who has served as president since its inception in 2019.

Famara’s team welcomes newcomers to Cuevas del Almanzora, leveraging the power of football as a shared passion and common ground. About two hundred people are registered in the association; every year, they collect twenty euros per head. The money goes to help each other. "If someone has a problem, for instance, a health issue, we use the money to cure them," says Famara about a project, his team, which is already more than a club.

A group of thirty Senegalese boys goes down to the Almanzora. It is seven o'clock in the evening, and the players have arranged to meet in the desert riverbed, which is totally dry due to the scarcity of rainfall and, according to the locals, also due to recent agricultural practices.

The players train many days a year, except for Mondays, rainy days, and cold winter afternoons. The whole atmosphere of Almanzora is masculine, with the exception of a couple of little girls who play in the surroundings, waiting for their kin. In Almeria, nine out of every ten Senegalese individuals are men, many striving to accumulate resources to better the conditions for their families back home.

"These goals were installed years ago, so instead of water there is football, the water never runs, only they run," observes Francisco, a resident of Cuevas del Almanzora, who watches the players touching the ball while leaning on the river's fence. The dust swirls skyward, and the boys disappear in a whirlwind of sand as the game intensifies.

They are the other club from Cuevas, the players from the Almanzora river, and each embodies the ethos that Famara instilled. The town’s official team, Cuevas C.F., has no Senegalese players. Cuevas C.F. competes in the Almeria’s League, equivalent to the seventh level of competition in the Spanish Football League. "No Senegalese boys are there simply because they remain unknown to them. It's a fine club filled with good-hearted people, but they don't have enough knowledge about our people," explains Famara, one of the few Senegalese who was able to federate.

He had even enjoyed a brief stint with Cuevas C.F. in 2017, a brief but memorable period that marked the culmination of his semi-professional football journey. "They needed a defender for the season's end and approached me," Famara recalls. However, he made his career as a center-back at A.D. Los Gallardos, where he spent six seasons defending the jersey of the neighboring club. "I was the first black player in the club's history." They clinched the league in 2010, coinciding with Famara's debut season as a football player in Spain. His sportsmanship throughout the season was lauded—he received an award for incurring just a single yellow card in the entire competition. "I outran everyone,” he asserts. The trophy, now a showpiece on a shelf in his living room, holds a Senegal flag above the television.

Famara and his younger brother, Elhadji, are watching a match between FC Barcelona and Atletico Madrid. They're hoping for a draw. "Football is my life," Famara admits, his football fandom not confined to the Spanish La Liga but also to the English Premier League, the German Bundesliga, and the Italian Serie A. When questioned about the secret behind his ability to watch any European football match at home, Famara responds with a knowing smile.

There are dozens of young men on Famara’s team, originating predominantly from the southern parts of Senegal, working in Almeria's agriculture sector, and uniting around a shared fervor for football. Ibrahima stands out as their stellar goalkeeper. "He's a great goalie," Famara lauds. Aside from saving goals for his countrymen, he is also the starting goalkeeper for C.D. Mojacar, another neighboring club, which also plays in the Almeria's League.

Ibrahima arrived in Cuevas back in 2018, following a stint in Italy. He speaks as many languages as an interpreter: Wolof, Mandenka, French, Italian and Spanish. He is 27 years old and shares an apartment with other Senegalese migrants in Cuevas. Seven years ago, he made a perilous crossing of the Mediterranean from Tunisia to Sicily, traversing an expansive sea stretch of three hundred kilometers.Ibrahima has been absent from several of Mojacar's training sessions throughout the year. Traveling from Cuevas del Almanzora to Mojacar, around twenty kilometers by road, has proven challenging. "Usually, I carpool with a teammate who recently had a disagreement with the club", Ibrahima elucidates. Nonetheless, training with his fellow countrymen in Cuevas ensures he maintains his physical condition.

The team has rented the municipal football pitch for fifty euros a half-afternoon. They divide into two smaller teams: the veterans wearing the yellow first kit and the younger ones dressed up in green. They warm up by doing rondos. In contrast to the strategy and tactics of conventional clubs, their commitment is to enjoy the game.

Famara resolutely guards the rear lines for the veterans, who lead by three goals as the halftime whistle sounds. Ibrahima, however, lingers on the same pitch, preparing for his run with the junior team in the second half. "They beseeched me," Ibrahima jests, the sole player whose hands are sheathed by vocation. As the second half commences, Ibrahima's vocal presence resounds on the field, shouting strategic commands to his new teammates. His presence seems to imbue the younger side with vigor. He foils the onslaughts and deftly uses both legs to dispel the encroaching pressure. On corner kicks, his fists ascend above all, propelling the ball into the clear sky of Cuevas. The junior team's enthusiasm doesn't quite secure the comeback, and the match concludes with a score of three to two.

Famara had the same problem as Ibrahima: he could not get to the stadium of Los Gallardos on his own when he was a federated player. "The board of directors took me to training sessions and matches." Famara expresses a warm sentiment for the chairman, Paco Picante, "a football man, a good person.”

Famara’s life changed when he met Picante. "We were at a construction site in Mojacar," Picante recalls. "I was the carpenter foreman and saw Famara through a window, digging a hole for a swimming pool all by himself. I was very impressed by his attitude. "We started talking about football, and a few days later, he was already training with us." Picante laments the reluctance of local clubs to engage with migrants, who are frequently young, sometimes even mere adolescents, who find themselves united by the challenges of solitude and labor-intensive work. "The clubs in the area are not interested in dealing with the migrants' situation, primarily due to the additional responsibilities that come with dealing with those who are undocumented. We Spaniards have a migration past; we should be more humanitarian," expresses Picante, who recognizes that signing Famara also changed the club's history. "He was our first black player. The very first of many."

Famara's team is now in the midst of a tournament, competing against other unofficial teams in the region.“We are playing against other Africans, laborer squads… If my team wins, we’ll throw a party, and if we don’t win, so will we,” says Famara, who has made several players laugh. The team trains by finishing off crosses in the imaginary area of the Almanzora, where sporting excellence is achieved in a different way.