- 13 Ways of Looking: a series by Lorena Endara

by Emiliano Valdés

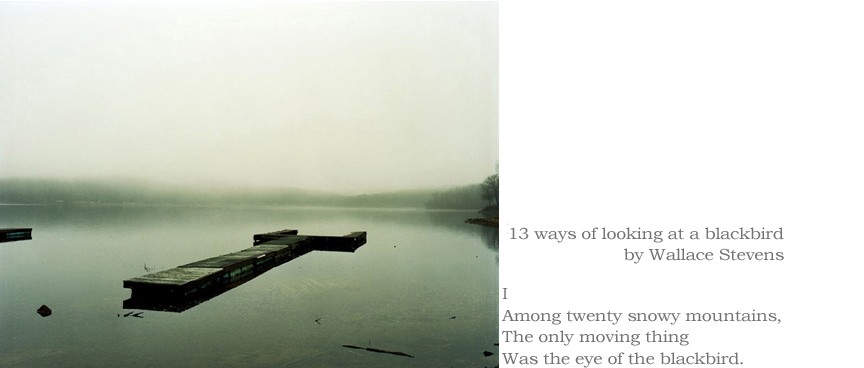

I

- A place, the way light shines upon it, the passage of time, the sights that change

throughout the day, the textures of the objects and the shadows that invariably

lie between the subject and the camera. Arbitrariness. These situations, the

matter of life as perceived not by our eyes but by our minds, tend to escape

the grandiloquence of image production today, usually steered by fashion,

manipulation and effective formulas. Those images deceive the trained gaze

stage-managing impressive subjects, bold colours, trendy subjects. But not ’13

ways of looking’. This series of photographs relies on the imperceptible to speak:

they depict barely anything at all and yet they tell everything. The secret lies

on the fact that reality, apparently, is made of facts and things just as much as

it is made of imagination. Perhaps it is because this series contains that exact

combination of the two elements that it manages to capture all that is around us

so well.

‘13 ways of looking’, a project that both feeds from and complements the poem

by Wallace Stevens by which it is in fact accompanied, is a series of photographs

by Panamanian landscape photographer Lorena Endara that portrays nothing

more, but also nothing less, than a place and the passage of time. It tells the

story of a location; it captures its essence, and by doing so reminds us of our

own story and of its brief duration. It is in the absence of narrative and through

a sort of meditative action that the author manages to convey a sense of the

transcendental. But the anti-narrativeness is only apparent: by putting together

a sequence of similar images of the same subject over a certain amount of time,

a story is told. Not through actions and events, but through the gaps between

them.

The thirteen images and the equal amount of verses from the poem work in a

symbiotic relationship. Words complement the construction of each discourse

and ultimately yield into a single one. Details, absent from the picture, are filled

in by the words, not illustrating or explicating them but rather working as two

different states of the same signifier. It is as if the words would tell not what is

shown in the photographs but what the photographs actually mean. Indeed,

the pictures are not simple illustrations of the verses nor the verses tell what

happens in the images, they provide different visions of a shared reality (and

imagination).

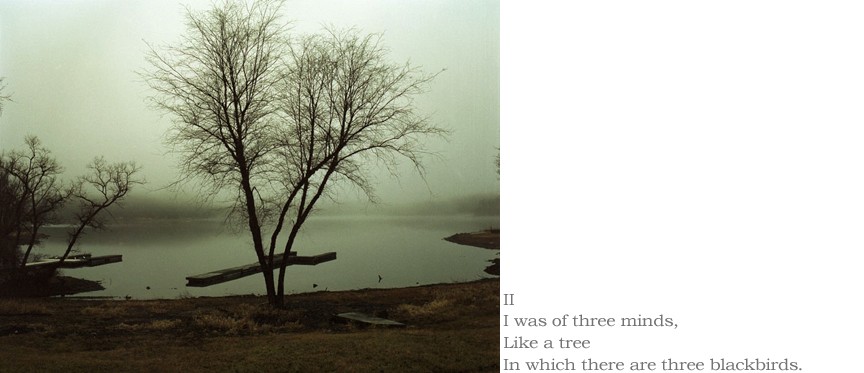

II

Since the beginning of representation, but particularly during the late 18th

century and onwards, landscape has been treated as the complying backdrop

for the psychological nature of the subject in almost every image. The context

was impregnated by whatever was being depicted, whether on a painting, a

photograph or even in literature, and it would reinforce the script of the action

or the personality of the characters. This treatment of the landscape has been

widely employed, even to our days, to intensify the motif of the scene, its

narrative, and its morality. The landscape would formalise (in the literal sense of

the word) the qualities of the subject or the action and surrender to a secondary

plane: mere set or counterpart.

But what happens when the landscape is both subject and context? What is

there to complement or to turn into when there is no action beyond that of reality

itself? The landscape cannot but acquire the form of its own temperament,

assume and re-present its own essence, its very nature, the image of nothing

but itself. In ‘13 ways of looking’ the melancholy and transcendental feel of the

pictures convey only the landscape’s own state of mind. And perhaps that of the

artist’s. The former is not manoeuvred to enhance a personality or the drama

being depicted. It presents its own drama: the construction of a reality, the

passage of time, the burden of being.

It is through the objectification of the landscape that it displays its full potential

as a subject and its connotations become explicit. Perhaps because ultimately

the landscape works as an indexing element of land itself and thus of the

context of human life that it is always read as more than it (re)presents. Through

its metaphorical nature, it can come to state precisely that which cannot be

described. Despite the fact that landscape has been, for the last 50 years,

approached from a culturalist point of view (that is, exploring the human

presence and its impact on the land), its nature and form continues to be used

as an analogy of human existence and investigative arena for philosophical

concerns.

But because landscape is in fact a cultural construction, it is through its

reading (and clearly also through its depiction) that it suggest a particular way

of understanding and responding to it and hence, a sense of belonging to a

particular moment in time and a place in the world. It is our understanding of

it that determines the way we relate to the world and ultimately, to life. This

is one of the reasons for which landscape photography has never ceased to

be a fundamental subject in the history of creation and in the work of our photographer.

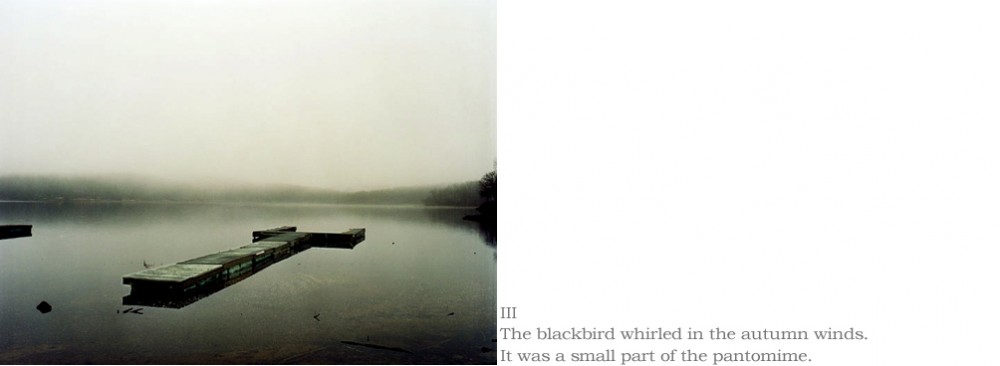

III

In an approach to photography that recalls that of Stevens to poetry, Endara puts

together several images of the changing reality of one place to build an evocative

and perhaps paradoxically realistic portrait of it. The image of that particular

corner of the world with a dock, a tree, a body of water, some snowy mountains,

perhaps a black bird, is built not through one but through several visions of it;

it is their summing up that gives us a sharp sense of its spirit. It is also in this

contradiction (the fact that a precise images is actually formed by many visions)

that the merging of reality and imagination takes place. This, in both versions

of ’13 ways of looking’, reality is the product not only of the creative process (i.e.

the imagination) of the authors but also of the recurrence and almost mantric

repetitive process of construction. Not accumulative but juxtaposing moments,

visions and thoughts, the poet and the photographer manage to put together a

place that is so subjective that becomes mordantly real. The series of pictures,

shot over a period of time, has the ability to speak not only of the place, but also

of its own process of change.

This working method is not coincidental or random, it responds to a thorough

interest in Steven’s “poetry of ideas”. The vision that reality is not static but rather

something created through passionate engagement with what is around us has

produced a work that rests on contemplation to produce an accurate depiction of

our world. But it is not the actual shapes or words, but rather their filtered images

that when finally do reach our mind, constitute the strength in both of these

works. By giving us different versions of an idea, Endara and Stevens emphasize

the unity of their subject and in doing so they highlight the importance of all

things arbitrary. And of the importance of imagination in the definition of reality.