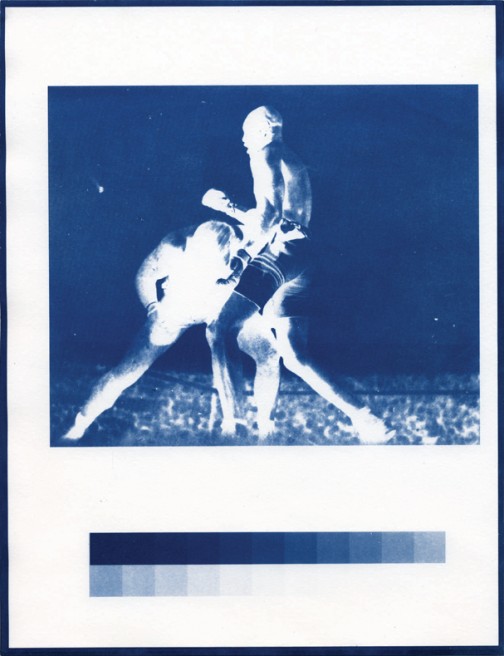

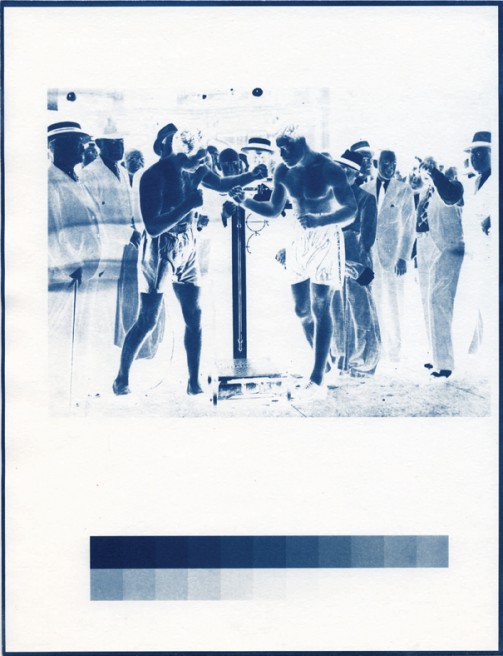

This series refers to my own re-appropriations of iconic images from the past that have left an indelible mark on cultural memory. I render these moments as Afterimages. In this case, a series of six cyanotypes is part of a larger body of research exploring the relationship between early photographic sciences, race, masculinity, and the representation of African-American athletes during the 20th century. The connections are traced through prizefighting lore with Afterimages in cyanotype of former World Heavyweight Boxing Champions Jack Johnson, Joe Louis, and Muhammad Ali; each of whom played key roles in developing the legacy of excellence and innovation that has become synonymous with African-American athletics. Boxing in particular plays a pivotal role at the beginning of the 20th century, a time when the heavyweight champion was considered the most powerful man in the world; a prestigious distinction in an era that sought to redefine masculinity though industry, rather than aristocracy.

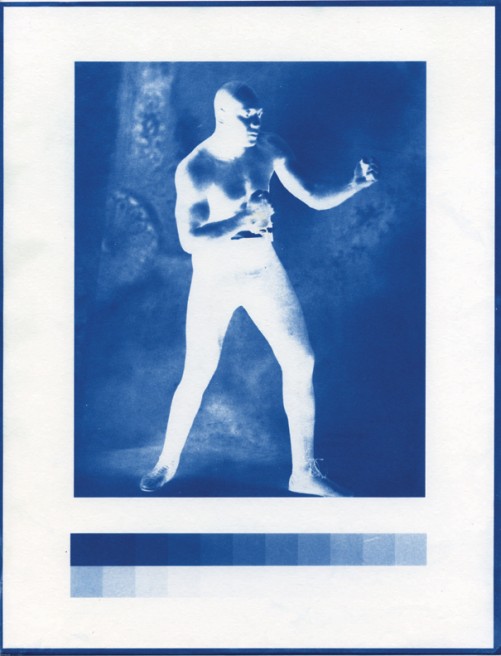

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s cyanotype proofs of Philadelphia boxer Ben Bailey, created in preparation for his 1887 Animal Locomotion Studies, inform my use of ‘blueprint’. Bailey was Muybridge’s only African-American subject in this archive and interestingly, it was with him that he unveiled his infamous anthropometric grid for the first time. This marks a point of racialization in Muybridge’s work, since Animal Locomotion was produced in a Post-Bellum United States rife with racial upheaval. Muybridge’s study placates biological racialists by repressively framing Ben Bailey as a primitive form with a representation that undermines his humanity by harnessing his masculinity. It is markedly emblematic of Jim Crow legislation after the Civil War in which lawful racism – disguised as segregation - was instituted to control the African-American population. Thus, with Bailey’s physiognomy in full view, Muybridge found his representation of him beneficial to the progress of both American race science and photography.

Muybridge’s use of Bailey can also be interpreted as a metaphor that mirrors the racism encountered by African-American athletes in the ring and on the playing field during this era. At this time, if a Black man emerged victorious over his White opponent, his triumph was attributed to an innate primitive instinct, while a defeat meant he was intellectually inferior and ultimately incapable of out-strategizing his White opponent. This paradox is reflected in both the instability of race science and in Muybridge’s photographic attestations to it. In order to win therefore, African-American athletes were forced to outwit their representation; in this case, a raw and structural form of photography such as the cyanotype, using defensive strategies to mitigate the inherent bias and racist officiating of the boxing ring. This holds true for the courageous Jack Johnson, whose 1910 defeat of Jim Jeffries made him the first Black Heavyweight Champion of the World, paving the way for the likes of the great Joe Louis and 'The Greatest’, Muhammad Ali. While Muybridge used cyanotype to frame Ben Bailey repressively, I use the method here to subvert the medium itself, by re-appropriating and uplifting not only these boxers’ most spectacular achievements, but also critical moments in cultural history.