“Photography is, and has been since its conception, a fabulously broad church. Contemporary practice demonstrates that the medium can be a prompt, a process, a vehicle, a collective pursuit, and not just the physical end product of solitary artists' endeavors.” [1]

- Charlotte Cotton

Often people use the verb take when describing the act of making a photograph. “Can I take your photograph?” “I took a lot of photographs when I was on vacation,” etc. This is most likely due to assumptive belief that photography is a process of documenting, which relegates all of the power to the subject and not to their own conscious and deliberate decision making.

Artists who utilize lens-based media as a form of self-expression often employ intellectual strategies for their work to address concepts beyond the subject in front of the lens. Although their subjects may be people, places and things, these artists are concerned with making images that communicate ideas that are more complex than only the subject at hand. These strategies include socially-concerned work, identity-based imagery, historical/cultural commentary through the use of archives, observational work to emphasize world realities, and self-referential work that acts as metaphor for psychology and the human condition. Using the verb make, instead of take, is more appropriate when describing these activities. It is a kinetic term that takes into consideration the artist’s ideas, decision making and informed perspective.

Photographs are complex communications between the maker and their audience, and they usually operate on multiple layers. This statement is my own personal interpretation of the work of the festival artists. I share these thoughts with the invitation for expanded readings and interpretations of the work, and not to be reductive.

In Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), painter Basil Hallward states “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself.” [2] This philosophical idea about art making is at the core of People, Places, Things: Metaphor & Meaning. All of these works are both records of the external world while simultaneously a communication of the artist’s inner world.

This concept is readily apparent in Katie Murray’s multi-faceted photographs in her series Wrestling. Wrestlers have been imaged since the Greco-Roman era, and Murray’s photographs certainly reference that tradition. They also are abstractions, and are steeped in formalism. Robert Adams, in his book Beauty In Photography: In Defense Of Traditional Values, states “Why is Form beautiful? Because, I think, it helps us confront our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning.” [3] Murray is finding deep meaning in the chaos of entwined wrestlers’ bodies, one of which happens to be her own son. In Murray’s photographs, the wrestlers become a new solitary totem, one that only exists within the photograph and Murray’s imagination. Her photographs are a personal document, a document of the external, and also metaphor.

Supranav Dash’s photographs of traditional Indian tradesmen, from his series Marginal Trades, are firstly the artist’s attempt to preserve a record of a culture that is rapidly changing. Many of these trades are disappearing as the world advances. Yet there are other concerns for Dash. One is the pure beauty of a well-crafted and visually arresting black and white image. Another is the references to Irving Penn’s and August Sander’s twentieth century portraits. And yet another is Dash’s personal perspective. Dash records remnants of his childhood experiences in Kolkata through the lens of an artist who has also spent informative time in the United States. I believe his insider/outsider perspective imbues the work with a pendulum-like complexity.

Visible Spectrum is a series and book of photographs by Mary Berridge that celebrate the unique individual personalities of young people who are autistic. Through exquisitely lyrical moments, light, and composition, Berridge presents her deeply personal familial experiences with autism. These are documentary photographs of people, and writings from the subjects and their parents that are included in the book also communicate what lies in front of Berridge’s lens. These photographs also share the care and love that the photographer has for the autistic community, and they advocate for society to learn more and accept those who navigate daily life divergently, yet just as profoundly. Photographers inherently are proponents of accepting people for who they are, and celebrate those differences.

Another artist who includes people in their imagery is Stacy Renee Morrison. The young women presented in her series Half-Way to the Rail Station in the Hot Summer Weather were never in front of the artist’s camera. Instead, Morrison has scanned, tightly cropped, and reproduced her grandmother’s grammar school picture, made in Poland in the early 1920’s. Although Morrison’s grandmother immigrated to the United States soon before the Third Reich came to power in Nazi Germany, a number of these young people possibly perished in the Holocaust. Morrison juxtaposes an appropriated archive with photographs of clouds that she personally made while visiting the death camp in Auschwitz, where many perished. The results are an elegy to all that was, a lament for the depravity of some, and a warning about our current cultural climate of xenophobia and intolerance. Morrison’s work presented here includes people, places and things, but the real communication resides outside of the subjects. Her true concepts manifest in the viewer’s mind as they navigate Morrison’s juxtaposed symbols.

The Australian photographer Shane Hulbert takes the making aspect of photography fully on by constructing and then photographing miniature models in his series Heroes of the Empire. In this work, Hulbert creates seemingly surrealistic tableaux that are at first disarming, but after a decoding one can glean that his work is more than just models and 3D printed figures. These images, rather, question the mythologizing of specific stories and events in Australian culture. What his works ultimately do for the viewer is to bring to question the mythologies of one’s own history, and one’s own societal and governmental actions and overreaches. Hulbert photographs first and foremost speak to the specific Australian experience, but also act as a spring board for critiquing all societies’ transgressions.

At first glance, Steve Giovinco’s landscape photographs, from his series churn and Darkland, appear other worldly, as if they were digitally generated, maybe even with Artificial Intelligence. But quite the contrary, his photographs are made with hours-long nighttime exposures in the farthest reaches of Greenland. Giovinco painstakingly traverses the land and sets up his equipment almost by intuition, because he has very little idea what the final results will look like. His process is meditative, and his only light sources are the moon, the stars, and sometimes the Aurora Borealis. With this work he addresses climate change and the fragility of both the earth and humankind, while using his artistic practice as a therapeutic and life-affirming antidote.

The urban landscapes of Lebanon, in the photographs of Manal Abu-Shaheen’s series Beirut, show a clash of cultures while documenting a city that has endured physical devastation from past conflicts. As a Lebanese-American photographer, one can imagine that Abu-Shaheen’s photographs are steeped in personal experiences of cultural contradictions. In this way, her images of Western advertisements in the city of Beirut act as metaphor. Again, we have an artist who recognizes inequity in front of her lens, and based on subjective choices of where to place the camera and when to press the shutter, Abu-Shaheen makes important declarations. The irony of advertisements promoting Western luxury goods juxtaposed against a Middle Eastern urban backdrop that is continually colonized by the West is sadly palpable in her work.

Irony is also apparent for Sebastian Meija in his series Quasi Oasis, which depicts palm trees in the heart of the city Santiago de Chile. One can almost sense the joy enjoyed by Meija as he pays homage with his camera to these living wooden obelisks that are so incongruous to the urban landscape. Meija is documenting the phenomenon, but the viewer understands these images as metaphors for urban isolation and survival. The palm trees predate much of the current urban architecture in Santiago. Are these images that celebrate the perseverance of nature and individualism in the face of all odds? Or are they requiems for an earlier time when the trees ruled, rather than humans? This probably depends on what mood the viewer finds themselves in that moment, and on whether the glass is half full or not. The beauty of Meija’s work, and of all the artists’ work included in this exhibition, is the understanding that there are no easy didactic answers, and that the world is a complex construct.

Gerard Franciosa’s landscapes, in the series Allison Pond, are his first person point of view meanderings through new growth suburban vegetation. The paradox in Franciosa’s work is that we view a nature completely manipulated by man, yet there is still solace provided by that denuded nature, both for the maker of the photograph and the viewer. Photographers such as Franciosa practice photography in order to make sense of their world, and to commune with nature. Viewers of these photographs come away with a sense of the peace and well-being the artist finds when making their work, and a new found appreciation of the often overlooked. Who could mistake these photographs for anything but koans used for enlightenment?

Twan Peeters’ photographs, from his series defusion and innermost, might just present a world after enlightenment has been reached. Each of his photographs represent his spiritual quest, and also a satori. Peeters’ photographs are perceptual abstractions, and he uses the medium of photography in order to investigate his metaphysical being. His work presents a world view that is akin to the tenets of Zen Buddhism. Peeters becomes one with his surroundings, and then through digital alchemy records that experience. Although his photographs are ostensibly of the world, of things that make up his domestic surroundings, ultimately his work serves as icons for meditation, not unlike the paintings of Rothko, or the mandalas of Tibetan monks.

Kaitlyn Danielson is also an alchemist. She is a time traveler, oscillating between now and the 19th century beginnings of the history of photography, through 21st century means. Her prints presented in this exhibition, from the series Secret Gardens, are digital copies of analog cyanotypes exposed through an electronic iPad. As an homage to the early female photographic pioneer Anna Atkins, Danielson reproduces digital images found on the internet by making cyanotypes through direct exposure of an iPad. Her work directly relates the ideas espoused about perception in the story of Plato’s Cave. In that parable, Plato asks what is reality and what is only a shadow cast by that reality? What at first glance appears to be simple renditions of flora, with intellectual diligence can unpack into a multi-layered discussion of the photographic medium and an ontological quest concerning the nature of being.

Rounding off the exhibition are the still lifes of Monika Dubinkaite from her series Nothing but gold. In our ordinary daily lives, we would never see the various objects that are carefully presented together in her frames, but the juxtapositions are rendered completely logical because of her meticulous attention to form and color. Nothing makes sense in these works, yet everything makes sense. It’s as if she is presenting the atoms that make up reality, while reorganizing them according to her own sensibilities. In her works we see the world anew through her eyes and perceptiveness. In fact, Dubinkaite not only makes images that wouldn’t exist without her perspective, she makes the viewer reevaluate their own assumptions and prejudices.

All of the artists included in this exhibition make subjective choices about when, what, where, why and how they want to image their world, and they create truly unique works that only they are able to make. These photographers do not take photographs. Instead, they make art that is subtle, multi-layered, and full of complex possible meanings. Please spend some time contemplating the choices each artist has made, and enjoy all of the possible meanings they present.

[1] Charlotte Cotton, “Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles,” (New York: Aperture Magazine, February 26, 2013), https://aperture.org/editorial/nine-years-a-million-conceptual-miles-by-charlotte-cotton/

[2] Oscar Wilde, “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” (London: Penguin, 1994), pg. 11

[3] Robert Adams, “Beauty In Photography: Essays In Defense Of Traditional Values,” (New York: Aperture, 1981), pg. 25

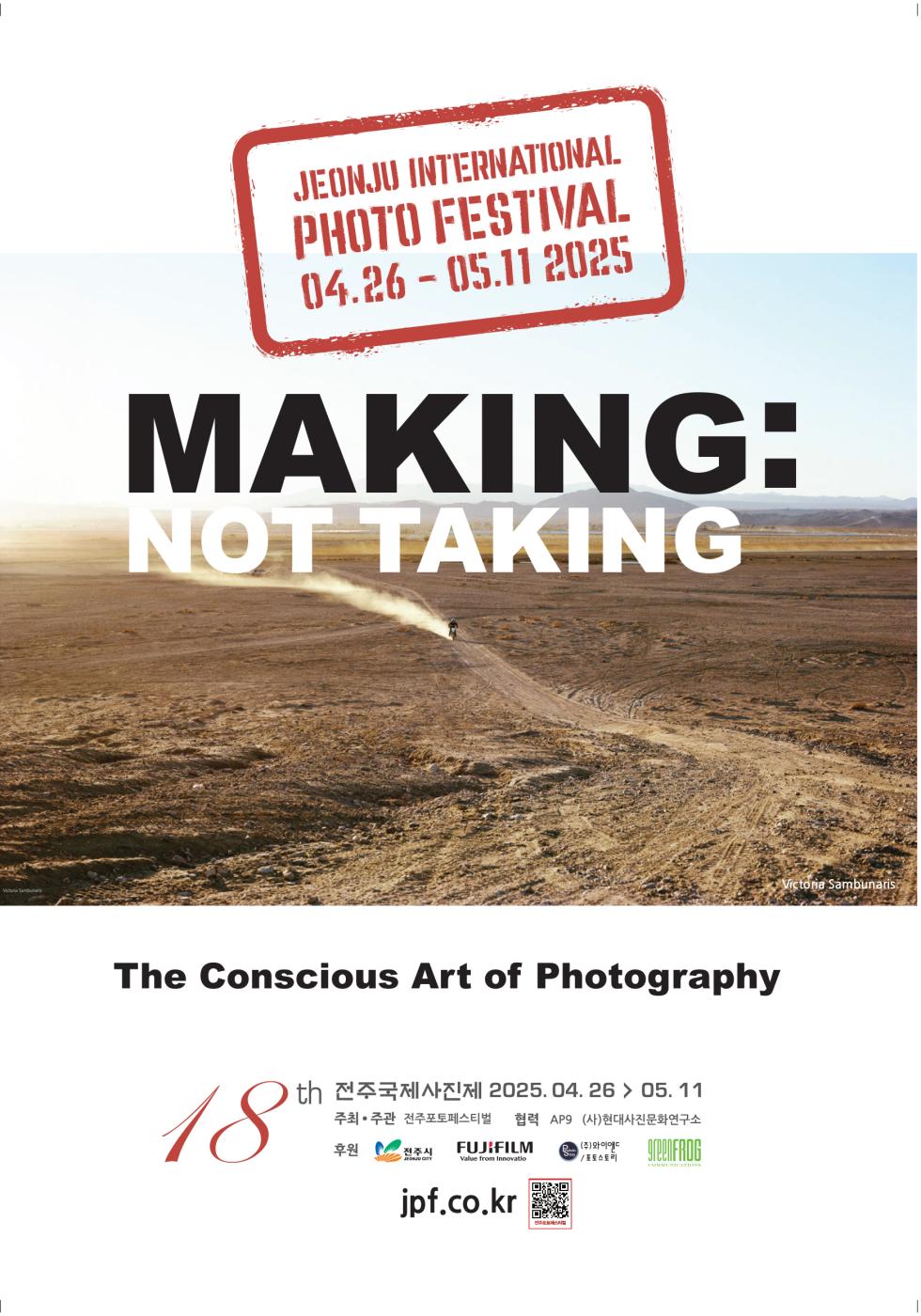

Special Exhibition: Victoria Sambunaris

For the past twenty-five years, Victoria Sambunaris has traveled the southwestern United States, crisscrossing through California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah in a car that is equipped with a roof-mounted tent called an Autohome. Sambunaris spends half of each year on the road, searching out landscapes with a 5 x 7 inch analog film camera, and more recently a video camera as well. Her practice includes deep and extended research on environmental issues, and the history of the places she images.

Sambunaris is a modern day Carlton Watkins (1829-1916), a photographer who spent much of his life following similar pursuits of documentation and conservation of the American West. Her recognition of the contemporary encroachment of man in these once pristine areas is akin to Robert Adams’ (1937- ) concerns as well. The natural yet vibrant color of Sambunaris’ prints, and their monumental scale, make these works unique in the pantheon of environmentally-concerned landscape photography.

When viewing these photographs, please look closely and concentrate on the mountain of facts presented. The information starts with the intricate details afforded by Sambunaris’ large format view camera, but that is only the beginning. In most of these works, there are human elements that are dwarfed by the scale of the setting. In one photograph, a dune buggy traverses a vast expanse of yellow sand, sandwiched by a saturated blue sky and its mirror image reflected in a body of water. In another, two seemingly miniature hikers slowly emerge from the vast terrain.

These human traces act in a manner described by Roland Barthes in his book Camera Lucida (1981). Barthes used the term punctum to denote small elements in a photograph that “prick” the viewer, creating an element of surprise. The French philosopher and semiotician wrote “The punctum of a photograph is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)…” Barthes believed that the punctum could only come from an unobserved accident or lucky happenstance, but as a non-practitioner he didn’t realize that photographers of Sambunaris’ caliber can will these surprises into existence through dedicated practice, and unwavering observation.

Victoria Sambunaris is making, not taking, truly important photographs. The making comes through her dogged research about the American Southwest, her attention to the complex climate crisis currently unfolding there, her intense travels, and her daily practice of making, making, making. The world learns from her work while we learn about the world. Through Sambunaris’ majestic works we gain understanding about its beauty, and also its fragility.