Lutsel'ke, a town on Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories, in the Canadian Arctic. A sliver of summer, like a crack of blue sky, wrenched out of the nine-month winter darkness. The smells of snow, whitefish, and char linger in the air. The ravens cawing from high up on the telephone poles. Dwarf spruce, lakes and rocks, and herds of migrating caribou. Neon signs flash “Arctic Laundromat.”

“Whenever I see a raven,” Prairie says, “I know I’m going to be bad, get into fights, get cheeky. Over in Lutsel’ke, I saw a dead raven. I was bad the rest of the day. But at least the raven didn’t get close to me. If it did, I would know that it’s my time to go.”

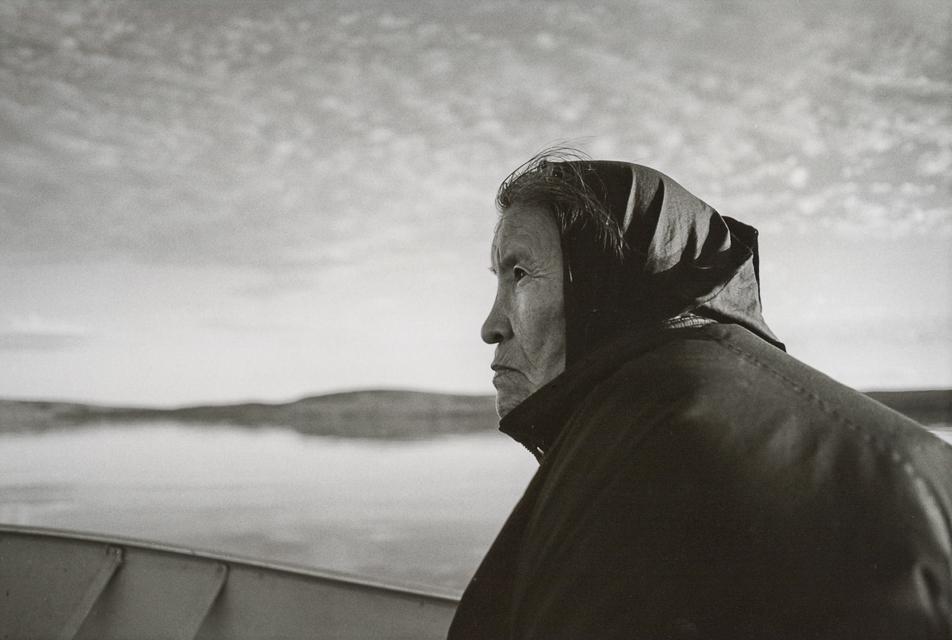

Prairie squints at the sun. The scar on her right cheek is finally quiet. The tension abates as the sounds of the water and the wind calm her, a song without musical notes that she alone can hear. Try as I might, I cannot hear her music.

I see a calm endless landscape but I know it won’t last. A cloudless cerulean sky darkens to steel gray in the moments while I change a lens. Even though it’s summer, the tamest time, I sense the danger that lurks beneath the surface, like the year-round permafrost. If the Dene people bury someone in this land, the ice forms underneath and pushes the coffin to the surface.

This is not the end of the world they tell me, but you can see the end of the world from here.