"Ultimately, photography is subversive not when it frightens, repels or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks."

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

In 2013, while interning with the Associated Press in Rio de Janeiro, a driver for the AP asked me a startling question. We were driving through one of Rio's favelas, what would be called slums in the United States. This particular favela, Mauricio explained, was the one in which he had come of age. He had spoken candidly for a while about what it was like to grow up in what is still known as one of the most violent cities on earth, and what it was like to be raising children in that city. I asked him if he worried.

"Well, sure, I worry like any other father," he said, "but at least my kids don't have to go to school in America."

I balked. This was a person who lived in one of the most violent cities in the world, a city which, until a few years ago, rivaled any given war zone for daily death rates. Brazilians tend to be proud of their complex history and culture, and obviously if Mauricio's kids had grown up in America, then they wouldn't be Brazilian, I asked him if that is what he meant.

"What I mean is that, when I drop my kids off at school, I know they will be safe. Yes, in Brazil there is youth violence, but it's almost always related to drugs and doesn't occur in school. In America I'd have to worry because kids keep showing up to schools and killing each other for nothing. Why is that? What is so wrong with America that in your country children are murdering other children and nobody can explain why?"

I said something about access to guns and Mauricio laughed. "Yes, we have guns in Brazil too. Still we don't have these shootings."

As we drove on in silence, I'm not sure what shocked me more- that I'd never truly thought about what I now recognized clearly as an obvious and vital question about school shootings in America, or the fact that I had no idea how to answer it.

Returning to the States in the fall of 2013, I began digging into the resources available. In my research, I found that boys or men perpetrated 99% of all school shootings in American history. Meanwhile, in Reload: Rethinking Violence in American Life, Christopher B. Strain highlights that, where information was available, over 90% of these school shootings involved a challenge, usually prolonged and systematic, to the perpetrator's perceived "manliness." I also learned that the gendered nature of violent crime extends beyond school shooting violence. Boys and men commit the vast majority of violent crime in American society. Why are males so predisposed to commit violent acts? And why is that fact seemingly so absent from any national conversation concerning trends of violence?

In Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, as Michael Kimmel explores contemporary prescriptions of masculinity in the US, focusing on how the lack of cultural response to such a huge problem. He notes that although socially conditioned gender expectations are a primary cause of violence in America, rooted in the country's own extensive network of myths, legends and origin stories, they are rarely considered a cause of anything at all. For many it is as if masculinity doesn't exist, and if you can't see something you can't change it. Perhaps this is why the nearly unanimous opinion held by scholars and experts that the phenomenon of school shootings, and other drastically increasing rates of violence in American society, is being caused by the culture's its prescriptions of masculinity, seems nowhere to be found in the national discourse. The choice as been made to ignore the greatest common factor (by far) linking one of the most perplexing and dangerous phenomena in modern American society.

Meanwhile, that same society expects its male population to navigate a myriad of social situations for which they have not been given the proper set of tools. For example, as boys are conditioned not to show weakness, and to "be a man", many are left without the requisite emotional self-knowledge necessary to process a wide variety of experiences yet unwilling to ask for help for fear that it might cause them to appear weak.

Of course, other factors play a role: access to guns, a mass communication system that tends to celebrate overt displays of power and force, the stigmatization of mental health issues, and unresolved racial and class divides all contribute to creating what is, statistically speaking, one of the most violent nations on earth. The problem is that while Americans have admitted they have a gun problem, they have yet to admit they have a masculinity problem.

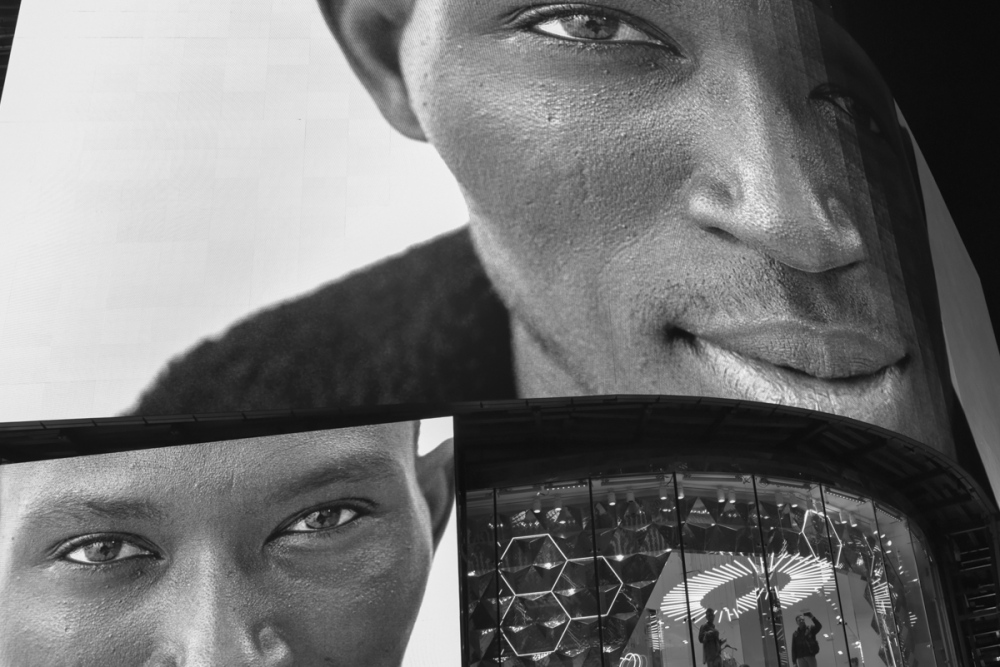

My feeling is that until we acknowledge violence as a largely male phenomenon in America, caused not by biological sex but by prescribed, enforced, but essentially changeable ways of being a man in America, we can never hope to mitigate the trends violence plaguing America and its people. In much the same way that many Americans tend to see past whiteness when thinking about race, the culture seems largely unable to see masculinity when looking at gender. Boys, as they say, will be boys. And that is that. The truth, however, is that gender is culturally constructed and enforced, which means it can also be deconstructed and adapted to new societal priorities. The purpose of this essay is to help catalyze a growing conversation about masculinity in America by creating a new perspective from which to consider the otherness of one of our most dominant narratives about gender. It seeks to make seen that which remains hidden right before our eyes. Instead of focusing on the stories of the countless victims of violence perpetrated by men, it turns its gaze at men themselves and the varied performances of their masculinity.

The photographs included here were selected from a body of work created during a fellowship at Magnum Photos and in partnership with its Emergency Fund. It represents the first stage of a long-term project designed to explore the creation and performance of masculinity in contemporary American culture. It is essentially observational. I made a decision from the outset to avoid chasing and making photographs based on either preexisting images or my own preconceived notions of how the subject might be best represented. The goal was simply to show up, look, and make images without another consideration. This approach "“ photographing before a consideration of where a potential photograph might fit within the larger context of a project "“ has created a continually renewed and evolving understanding of the subject.

My feeling is that until we acknowledge violence as a largely male phenomenon in America, caused not by biological sex but by prescribed, enforced, but essentially changeable ways of being a man in America, we can never hope to mitigate the trends violence plaguing America and its people.