Public Project

Chapter One: Codes of Conduct

Text by: Sumeja Tulic

One buys a bed, lays down a carpet, unzips the suitcase, hangs a clock, and eventually opens the window to the street, which from then on will be called “my street.” With few variations and much more minutiae, the immigrant begins the process of settling into the new home. This new home will be tasked with providing shelter and protection. It is where the most intimate aspects of life will take place: dreaming, remembering, and narrating.

Emphasizing the complexities of this immigrant experience, in The Migration of Djinn – Chapter One: Codes of Conduct, Btihal Remli (b. 1987, Germany) works with intimate spaces and rituals. She combines images of domestic, private space and handwritten text to scrutinize the belief in djinn in the Maghreb-Muslim communities of Germany.

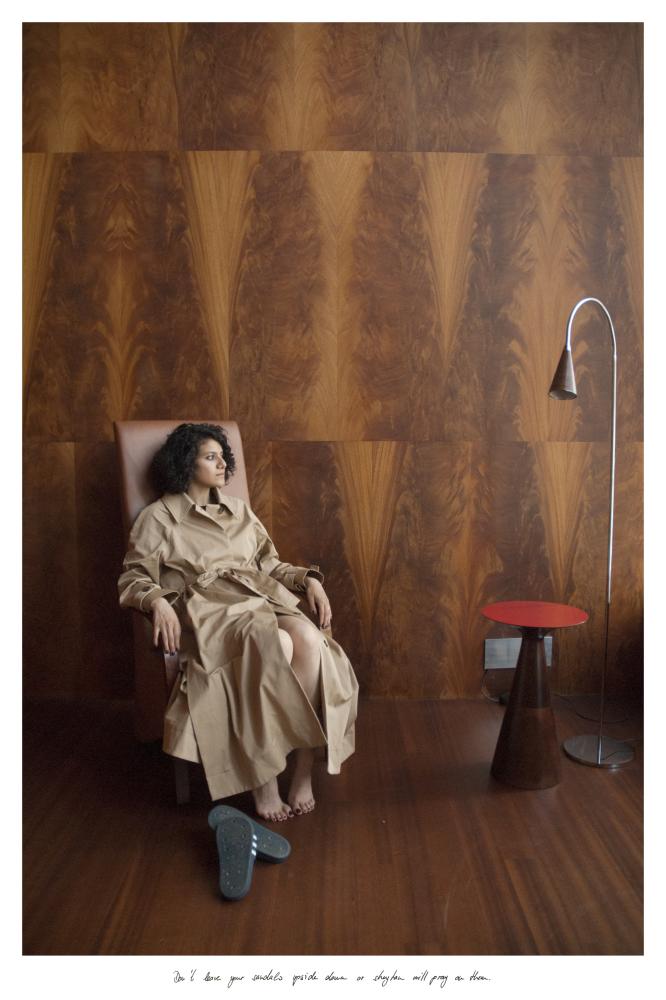

The series consists of self-portraits showing Remli dressed in a trench coat, a Western sartorial choice, which Remli describes as “second skin” that the immigrant puts on in order to adapt. “What’s beneath the coat stays the same, just even more hidden,” she explains.

Remli’s self-portraits are set in a domestic place, where she is seemingly transgressing instructions relayed by elders of her community.

“Don’t pour hot water into the sink after sunset, or you could anger the djinn.”

“Turn around mirrors before you go to bed, or shaytan will watch you sleep.”

“Don’t use the word djinn at home, or you could summon them.”

The instructions themselves are written out by hand along the narrow margin of each image. Some of these prohibitions stated in the vernacular Arabic dialect of the Maghreb region and handwritten in Arabic script by Remli’s mother are also presented as neon signs.

The belief in djinn is essential to the Islamic faith. Djinn are described as creatures made out of smokeless fire, taking animal or human form while having neither inherently bad nor good qualities. According to Islamic texts, djinn are able to possess humans and control their behavior. Fits of anger, seizures, speaking in tongues, physical and mental illness, and even social misfortunes are said to be the workings of the djinn.

Although some of the Moroccan immigrants Remli spoke to defined their belief in djinn as superstitious, all of them adhered to the guidelines protecting them against the djinn. The implications of such belief have far reaching consequences, which Remli is quick to point out. A research paper she found while working on the project identified that a group of psychiatric patients in the Netherlands, all of whom were Muslims from Magreb, attributed hallucinations and similar sufferings to the workings of djinn.

The seriousness of the subject matter is duly reflected in Remli’s photograph.The stoic expression of her face is not of defiance or disbelief but one of studious anticipation: What will happen next?

This Project has been supported by the Bayreuth Academy of Advanced African Studies, the City of Cologne, the Iwalewahaus and Nora Noor as artistic advisor.

4,851