To my mind, I think that we’ve reached the limit of what the 20th-century media can do and should do. Frankly, I think they should all back out of the news reporting business...Their way of looking at the world is so fixed and intransigent. Their ethics and their structures (which by the way, we're set up by white male capitalists to bring credibility to their advertising platforms) are so fixed that they no longer suit our world and it’s stories, which are much, much richer than when those initial ethical standards were created.”

—Stephen Mayes

As I reflect on my most recent essay and interview with Stephen Mayes for Visura Media’s Reframe Column, I realize that I did not address one particular topic in Mayes’ history that I personally feel merits attention. I am speaking about the Positive Lives, Project’, its effects on his thinking to date, and where the project lives along the moral arc of contemporary photography as we step off the bridge between 20th and 21st-century photographic social storytelling.

‘Positive Lives’ was a “photographic project about a medical condition that became a social condition” which focused on the lives of those living (and dying) HIV positive, as well as their families. Developed and published between 1991 and 2010—this project was a collaboration between “Lyndall Stein of the Terrence Higgins Trust, Stephen Mayes and the photographers of the Network agency in London. The project premiered in 1993 at FotoFeis, Glasgow and at London’s Photographers’ Gallery, accompanied by a book published by Cassel.”

Stephen Mayes explains in his article on World Press Photo Witness Blog on Medium in Dec 7, 2017:

The project made no effort to document clinical symptoms and focused instead on the social responses that made the HIV epidemic unique. From the first recognition of the condition, fear and bigotry caused extraordinary conditions of suffering with reverberations far beyond the vulnerable groups and the diagnosed individuals. “Positive Lives” included sons and mothers, politicians, activists and carers. It contained studies of grief and loss, faith, bigotry, stigma, anger and love, that reached deep into all levels of society.”

The project’s focus on the person over the disease when visually presenting the story gets to the core of Mayes’ vision of the importance of producing comprehensive visual storytelling.

As Mayes described in an article for World Press Photos’ “Witness”:

“At that time in the early 1990s the narrative of “planet AIDS” was told mainly in 80-point headlines which severely limited information, carried little nuance, and drowned compassion in a sea of populist cant. And yet as soon as one scratched the surface it was hard to find anyone without some connection to the epidemic. For some, it was the solitary terror of nights alone in a hospital, or the bewilderment of parents, the courage of carers, the ripped-out-hearts of partners, befuddled educators, or confusion caused by the cruel rhetoric of ignorant politicians. For millions, the epidemic was understood as an entertainment enjoyed with callous glee in the writings of tabloid journalists who created a bête noir and stuck it daily with manufactured outrage, pitiless wit, and hateful slander. Everyone was touched by the epidemic. While busily disclaiming involvement and accountability, all of society had a finger on the pulse and everyone contributed to the sickness that ravaged society.”

In our recent conversations, I briefly spoke to Stephen Mayes about this project and asked him to reflect on it now that more than 10 years have passed.

He reflects:

“It was an extraordinary challenge to work with photography to express the real but intangible issues that came with the epidemic, and one might think that documentary photography would be particularly limiting when creating visual representations of abstract concepts such as bigotry, grief, and faith. But several factors combined to mitigate the difficulties. Breaking the whole into complementary chapters relieved the strain on each individual representation and allowed the whole to speak; the extraordinary culture of the Network agency allowed the group to work as an ensemble rather than the more familiar collection of soloists so often seen in group projects; maybe most importantly, this was not an exercise in bleeding heart validation but was focused hard and square on finding practical applications for the work. Each new host was encouraged to adapt the work to suit their local needs and the appearance of the project veered wildly between territories and across time as it was applied in the service of health education, gender empowerment, political activism, fundraising and many other needs defined by each new host. It was great to offer emotional comfort but the number one purpose was to save lives and although I don’t know how we could validate this, I have to believe that someone somewhere is alive today who might not have been without the work of Positive Lives.”

As I think about ‘Positive Lives,’ I see parallels to a number of other stories today regarding gun violence, climate change, mental health, immigration, and so many other topics. Everyone is touched or affected in some way by these issues. So, how can photography contribute, in ways to the resolution of, and/or the discussion around, the issues of our time?

Our understanding of journalistic ethics and objectivity are being scrutinized and questioned by a rising group of underrepresented voices across the creative and professional spectrum. These voices are demanding better representation and a seat at the table as leaders and contributors in photography, photojournalism, and documentary photography.

As the industry continues to evolve, the ideal practice of implementing open discussions empowered by a multitude of professional and creative perspectives will nurture a culture that values the need for constant (re-)evaluation when understanding, brainstorming and implementing successful solutions to define the current and future landscape of visual storytelling, art, and media.

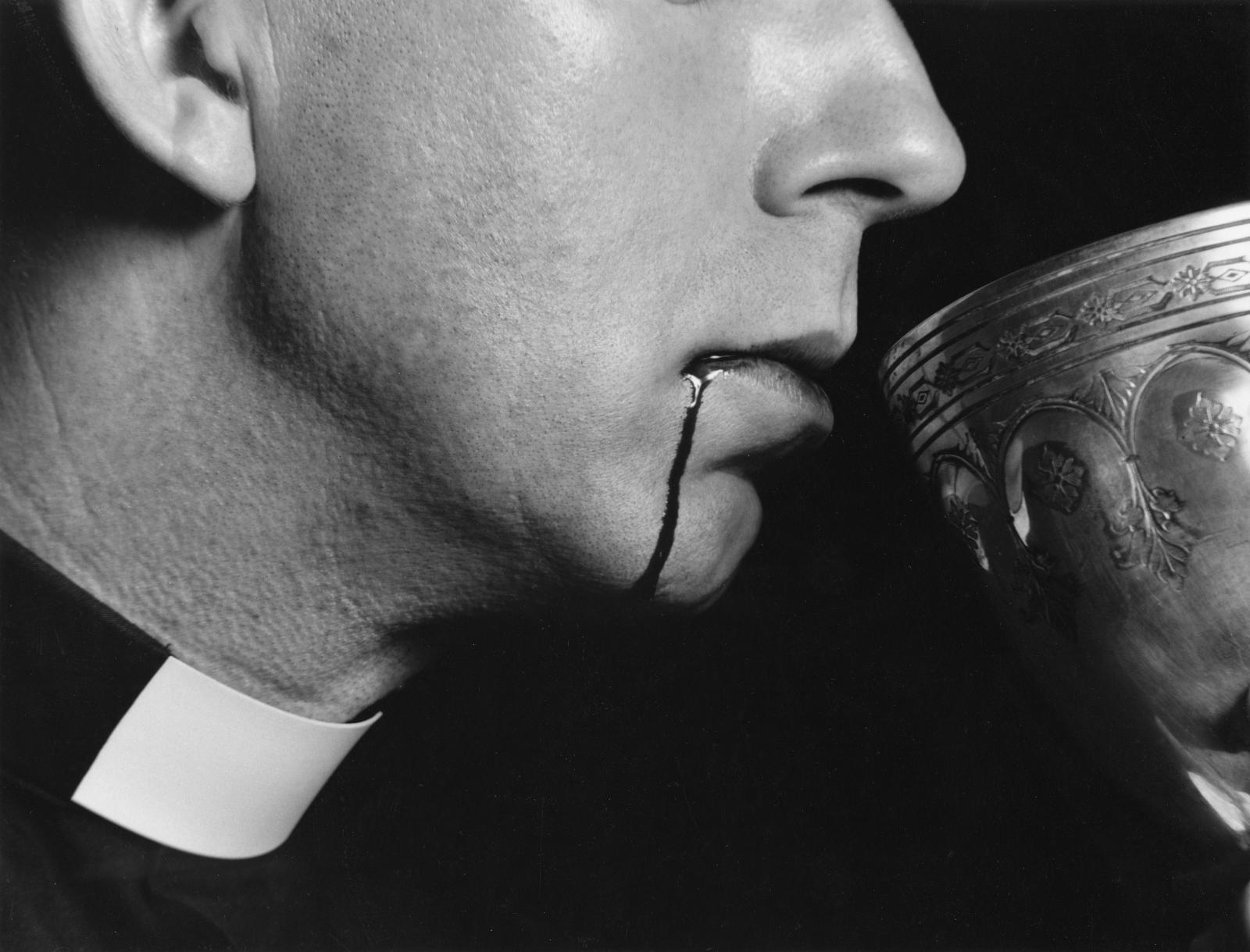

- Positive Lives 1993: Children living with such a stigmatized condition were in a peculiarly complicated space and documenting their situation presented particular problems, resolved here in stylized anonymity using Polaroid transfer. “Telling children passes the burden of secrecy to them.”

- (1993) © Jenny Matthews

NOTES FOR INSPIRATION

As the director of the Tim Hetherington Trust, Stephen Mayes is constantly looking for photography projects, both personally and professionally. In his quest, he looks for stories that are not only innovative but also look to both shine a light on the issues of our world and interact with today’s issues on a deeper level in hopes of creating complex and subtle photographic narratives.

During our interview, I asked for examples of work that he found inspiring. He pointed to photographers like; Debbie Cornwall, who is “exploring American power with a complex weave of documentary imagery that illustrates fictional circumstances”; Laia Abril, and her fearless and fierce eye towards “telling intimate stories which raises uneasy and hidden realities related with sexuality, eating disorders and gender equality”; Yael Martinez, a Mexican photographer “exploring the connections among poverty, narcotraffic, organized crime, and how this affects the communities in his native Guerrero”; Josh Begley, a Data artist, filmmaker, and app developer who created “Metadata+, an iPhone app that tracks every reported United States drone strike”; Mickalene Thomas, a multimedia artist “best known for her depictions of African-American women and celebrities through collages of acrylic, enamel, and rhinestones”; and Tomas Van Houtryve, a Belgian “conceptual artist, photographer and author whose major works interweave investigative journalism, philosophy and metaphor.”

Mayes’ eye for photography is ever looking out, rather than in, and clearly there is still an amazing amount of innovation and work being done by imaginative, concerned, and focused photographers.

“As creators, it's easy to get lost in self-reverential admiration of our own work but if we’re working on a documentary medium we must not lose sight of at least two additional key contributors to the success of our work: the subjects who contribute their experiences and often their identities, and of course the viewers. It could be argued that if we expect imagery to have real-world consequences, it will be the viewers who carry the greatest load as they interpret and act on what they see.”

The imaginative photographers Mayes explores often look to new media forms to explore and contextualize endemic and historically deep issues. This, ultimately, feeds Mayes’ enthusiasm for the future of photography and photographers. Where Mayes sees potential is in expanding our conversational methods through using the new media tools and philosophies of documentary storytelling today to explore the different ways our voices express themselves.

These new forms of storytelling also get at the disquieting issue of the lack of faith in the journalism industry and the perpetual lack of trust of the photographic (and now video graphics) image. In his signature futurist style, Mayes asks us to jump headlong into this uncertainty and the conversations therein. Mayes asserts that if the image is not to be currently trusted to stop trying to control the digital image by analog means and, instead, start talking about how we personally relate to the issues presented through the image and work to connect disparate groups that have otherwise become balkanized.

“One of the things which is really clear in my mind is we have to let go of this notion of the image as evidence. Words can be evidence, but we also know that words can be fiction. It can be both. It's not either or. But the notion that the photograph has to be evidential is really going to kill us.

It turns to the philosophers to ask, what is truth? I cannot begin to define what truth is. People have been trying to understand that for several millennia. The fact is that there are multiple truths, not just a single truth, something I think we also have to accept. For example, Nelson Mandela was both a freedom fighter, as well as a terrorist. He was both and I think you have to accept that. If you are only accepting the part of the history of Nelson Mandela as a terrorist, you erase part of his history, and you're telling an untruth.

Fiction can release us and fiction can be used absolutely in the service of documentary and of understanding the world. I think where we are going to die if we insist forever on the notion of facts being our savior, cause they're not. Facts alone are not going to save us. And you know, it's awkward to say that because we get into Trumpian language of post-truths and alternative facts and stuff like that, but that's not the point. The point is that there are ritual ways to describe the world and the facts alone obscure as much as they reveal.

The smarter the computers and cameras get we are going to start being able to photograph what we know rather than what we see. And I think that is very interesting.

For example, we all know that most cars have four wheels but without the use of mirrors or trick angles a conventional camera is limited to showing two or at most three wheels. We’re so inured to this convention that we forget that the facts alone do not tell us the whole truth; not only does each individual photograph deny the truth of the four-wheeled vehicle but taken as a whole it could be argued that by the consistency of its representation photography perpetuates a systematic exclusion of the truth.”

Photography is a powerful social tool. The photographic image, like any tool, opens up as many doors for good as it does for harm. As we previously touched upon, this has been a reality since photography’s inception.

- Positive Lives 1993: Sir John Junor, Mail On Sunday columnist (1993) © Steve Pyke / Getty Images

MOORE'S LAW & THE BREAKDOWN

As Moore’s Law —the observation that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit double about every two years. I.e. the reasoning behind why technology seems to be moving faster and faster each year - because it is— accelerates our industry into an unknown singularity, thinkers like Mayes remind us that we must be open to innovation and listen to the ever-increasing diversity of voices coming about today if we ever hope to avert being left behind in a revolution that is not concerned with waiting for us.

Photojournalism and documentary photography, on every level, must adapt and be receptive. The positive side of this growth, however, is as the breakdown of the traditional structure, the discussion around introducing and accepting new and alternative sustainable financial models for accessing, searching and discovering new talent and journalistic and documentary storytelling lies in wait for the industry to test and potentially, to utilize.

What is important to remember is that the balance of power within the industry needs to be more equally distributed among all parties involved in the photojournalistic process; creators, editors, developers and publishers alike. Rather than maintaining an economic system that exploits content creators and supports a ‘gatekeeper’ mentality reliant on select individual figures who have the power to deny or accept work or talent, a new system should be considered. One that is built on fostering innovation, diversity, complex narrative development, openness to critique and discussion, and cooperation throughout the entire industry.

As Mayes postulates in his essay, ‘The Only Certainty is Change’:

“[Today], as the once-familiar clients of the supply model have dropped off our “must-call” lists it has become commonplace to refer to photographers as “publishers”... When the author becomes the publisher we are suddenly liberated from the tyranny of the supply market: now we are truly masters of our destiny: as publishers we decide what we want to talk about, we choose the media to best express ourselves and we select the distribution platforms most appropriate to reach the audience that we determine and furthermore we retain control of our relationship with our communities (or whatever group we identify as the people-formerly-known-as-audience), and we have an active role in managing feedback and outcomes. We even manage the opportunities to monetize our presence in culture. It baffles me that anyone could consider the old system to be better, where simply for the security of a contracted check we were ready to concede the choice of what we photographed and we abandoned our responsibility for the image at the editor’s desk (or art buyers collection point, or the gallery owner’s back office). We are no longer defined by a single skill (to make images) nor beholden to clients to decide what to photograph, when and at what price.”

As more and more developers and publishers work to fill the void of traditional photojournalism economic and creative development structures, the key is that whatever platform or model creators use does not jeopardize the value or sustainability of the work in itself. Creative, effective and well-developed work must always be properly valued and sustainable.

Written by Clary Estes

In Collaboration with Stephen Mayes