Project Text

Grand Lakou Gonaïves

Lakou Badjo is one of the three grand Lakou Ginen* of

Gonaïves in the Artibonite region of Haiti. The two others are, Lakou Soukri and

Lakou Souvenance. All three were founded prior to the Haitian independence in 1804.Lakou Badjo, the oldest of the three spiritual compounds was founded in 1792, 12 years prior to independence in 1804. The founder, Badjo Pady, was born in Haiti and came with his mother and father, Azo Pady, to the area which is now the Lakou. Little is known about Azo Pady except he was born in Yorubaland and was captured and enslaved, brought to Haiti and escaped with his wife and children to join the revolution. The people of Lakou Badjo believe both Badjo and Azo Pady were present at

Bwa Kayiman on the 14th of August, 1791 and it was almost a year later when they crossed the mountains and arrived in what is now Gonaïves.January 3rd is celebrated as the birthdate of Badjo Pady and the start of the 9 day annual celebration of the founding of Lakou Badjo. My first visit to Lakou Badjo was in July 2014 and since then I’ve had the honour of numerous visits to the Lakou as guests of the Grand Sèvitè of Badjo, Dorsainvil Estime, and his wife, Manbo Yolta Pierre.Badjo Pady was of Yoruba descent through his father who must have counseled him on the Yoruba deities and religion which includes the Yoruba deity, Ogun, in Haitian Vodou he is the Lwa Ogou. Like most Lwa in Haitian Vodou, there are many manifestations of Ogou – Ogou Feray, Ogou Batala, Ogou Panama to name a few and at Lakou Badjo there is Ogou Batagari [Badagari]. I don’t think it’s stretching too far to conclude that Azo Pady might well have been from Badagari in western Nigeria which is why Ogou Batagari is the Lwa after which the Lakou is celebrated and named following the Nago rite which itself originates in Yoruba.Ogou is the Lwa of fire, of iron, of strength, the warrior, the politician and red is his colour. Scared to Ogou is his sword or machete. With these characteristics, it is easy to see why he was central to the revolution and remains a revolutionary hero. Nonetheless Ogou is also a benevolent Lwa, generous and loving to those who serve him and generally easy to please with a good cigar and generous shots of preferably, Barbacourt rum but also, I’m sure, happy with a glass of Clerin.Badjo Pady is buried in the Lakou cemetery. The original tomb was partially destroyed during the 2006 floods but it has recently been restored though not fully decorated. I asked the Sèvitè what happened to Azo Pady. He replied that he was also buried in the cemetery but one day his tomb just disappeared never to be seen again. The story told is that he tired and decided it was time to return to his home across the ocean back to Ginen*.

The body as archive of our collective ancestors. In the beginning..

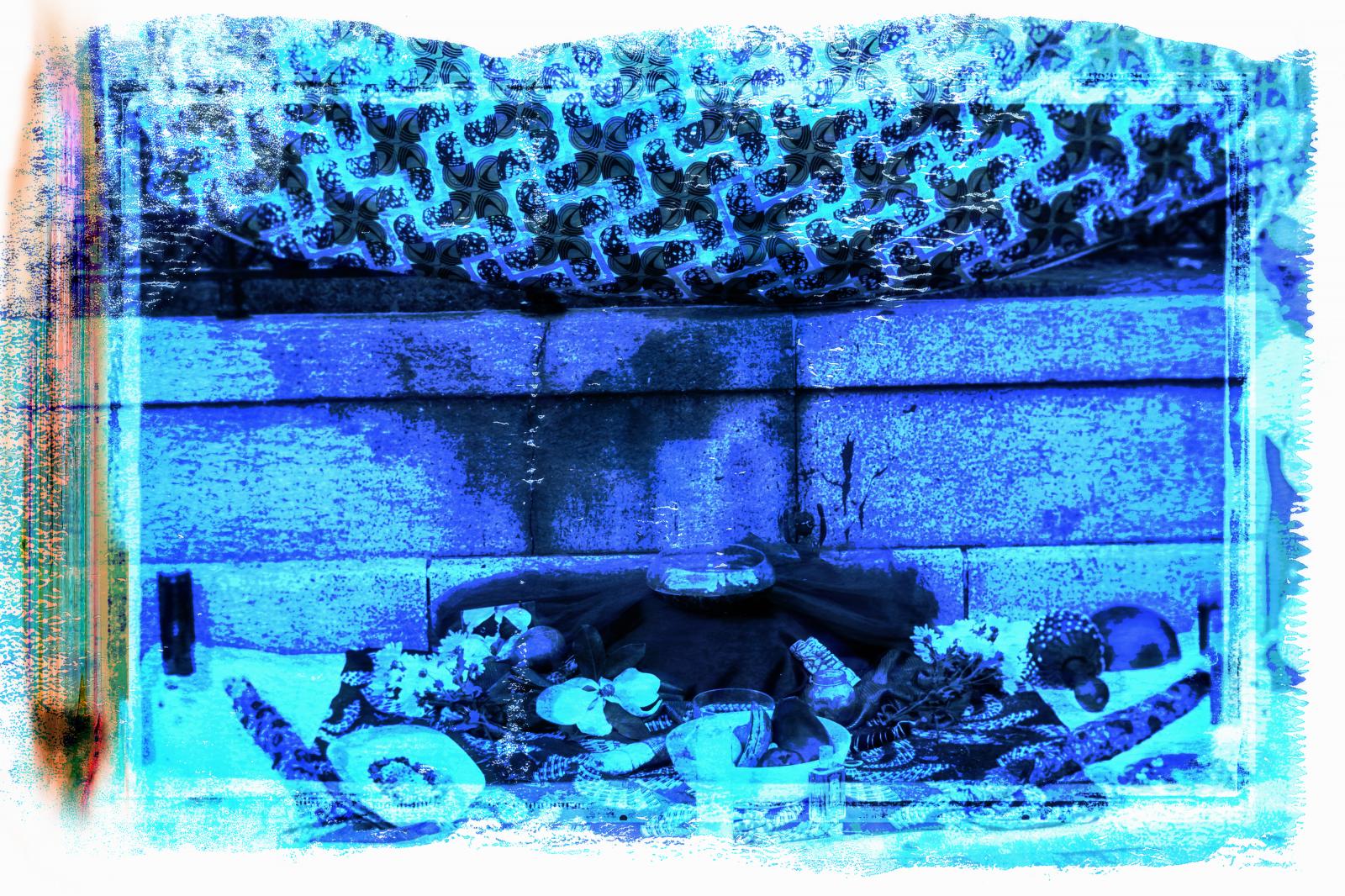

The photographs [here and elsewhere in this series] are embodied with multiple meanings such as what lies within and between the visible and invisible. To Know or to Imagine requires a LOOKING which connects the percipient to the visible movements and interactions as well as the absolute knowledge that the invisible too is present. The movements are both independent of those involved but are also a part of them. There lies the duality of the visible merging with the invisible in a constant state of fluidity. We should also be acutely aware of the body as a sight of memory. What we witness, if we LOOK that is, the duality and fluidity, all that takes place, is taking place, has passed from and between ancestor to ancestor, from the once visible to the invisible, and eventually returning to what we discern as the body in flesh.

The first two photographs above are taken from the Seremoni in honour of Lwa Ogou Batagari, which takes place in the peristyle of Ogou. Everyone except the Sèvitè, must wear white for all Seremoni in the presence of Ogou Batagrai. The Seremoni begins with rituals carried out by the Sèvitè and other senior Hougan’s and Manbo’s such as setting out food, cakes, drinks and other ‘Manje Lwa’ [food for the Lwa] and the pouring of libation which for Ogou is rum.

The second set of tw photos are from Lakou Soukri, a one day Seremoni to celebrate the Lwa of the Lakou, Bazouwadewongol. Lakou Soukri is Kongo which is a Petro rite although the Lwa are mostly from the Kongo and like Nago which draws Lwa from Yoruba, Kongo draws Lwa from Kongo. Again one can safely say that the majority of enslaved people in Haiti came from the region that now covers Ghana, Benin, Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon and the Congo and brought their spirits and deities with them. OF course the spirits have changed and reformed into Haitian Lwa whilst still maintaining clearly visible roots in West Africa. Other Lwa are Haitian in origin and may well have Taino influences as well.The Seremoni at Lakou Soukri is led by the Sèvitè, Manbo Marie Camie Delva. It took place in the peristyle and outside and included sacrificing of three goats and four chickens. Before people make derogatory judgements about ‘animal sacrifice’ I would like to point out that animals killed in sacrifice are killed in a far more humane manner than those you find in western supermarkets wrapped up in plastic and styrofoam containers. Like Halal and Kosher meats, animals are washed, and prayers are said before the animal is killed and they are honoured in their death with thanks. Not all Lakou’s or Hounfo’s engage in animal sacrifice though of course, like people throughout the world, animals are killed, cooked and eaten as regular food.One of the most important aspects of Haitian Vodou and other indigenous belief systems is the notion of Intent. Before you cut a sprig of basil or mint, you need to ask permission and state your Intent. In this case the Intent is not to harm but to honour the animal and to subsequently provide energy to the Lwa and the people. The Intent behind the supermarket chain is simply to kill the animal to provide food and to create a distance between death and the dinner table to such an extent that one does not even consider they are eating an animal.

*Ginen – Guinea, understood to be Africa, where the spirits are born and where an initiate returns after death, the place, Lafrik Ginen. It is also the principle that ‘supports and directs’ all Vodou teaching. It is a state of mind, a belief. Ginen is what anchors Haitian Vodou to Africa, the life force, the energy on which the spirits live. In Vodou there are rituals and there is order but there is also the freedom to imagine what you wish.** Ritual dance is not a performance in the theatrical sense. Rather as

Maya Deren explains, it is a ‘meditation of the body’, an act of ‘reverent dedication’ and an ‘exemplary demonstration’ of the principled in action and as such is itself, principled’. In ritual dance there is order which is determined by the Rite, the Lwa and by the tambour, though without understanding this fact, one might be oblivious and simply see ‘dance’. Ritual dance like possession, is transformational. Both enable you to free yourself by providing you with the opportunity to ‘loose your life’,

‘Pédi lavi-ou‘, even if only for a few moments.[

Pédi lavi-ou’ from a song by Bookman Eksperyans quoted from Nan Domi]