Caption:

African peoples have historically mediated life through speaking to the past as a way of moving through the present to the future. Here in our spiritual practices we speak with our spirits not as worshipers but as mutually dependent energies that we feel with our bodies but cannot see with our eyes; the visible to invisible and invisible to visible, an African Futurism guided by ancestors and traditional healing practices. To be here, to be past and to be future has required of us Black peoples, what poet Nicole Sealey, describes as an “hysterical strength” – not a “freak occurrence” but a persistence for and of survival. [1] Hysterical Strength by Nicole SealeyIn

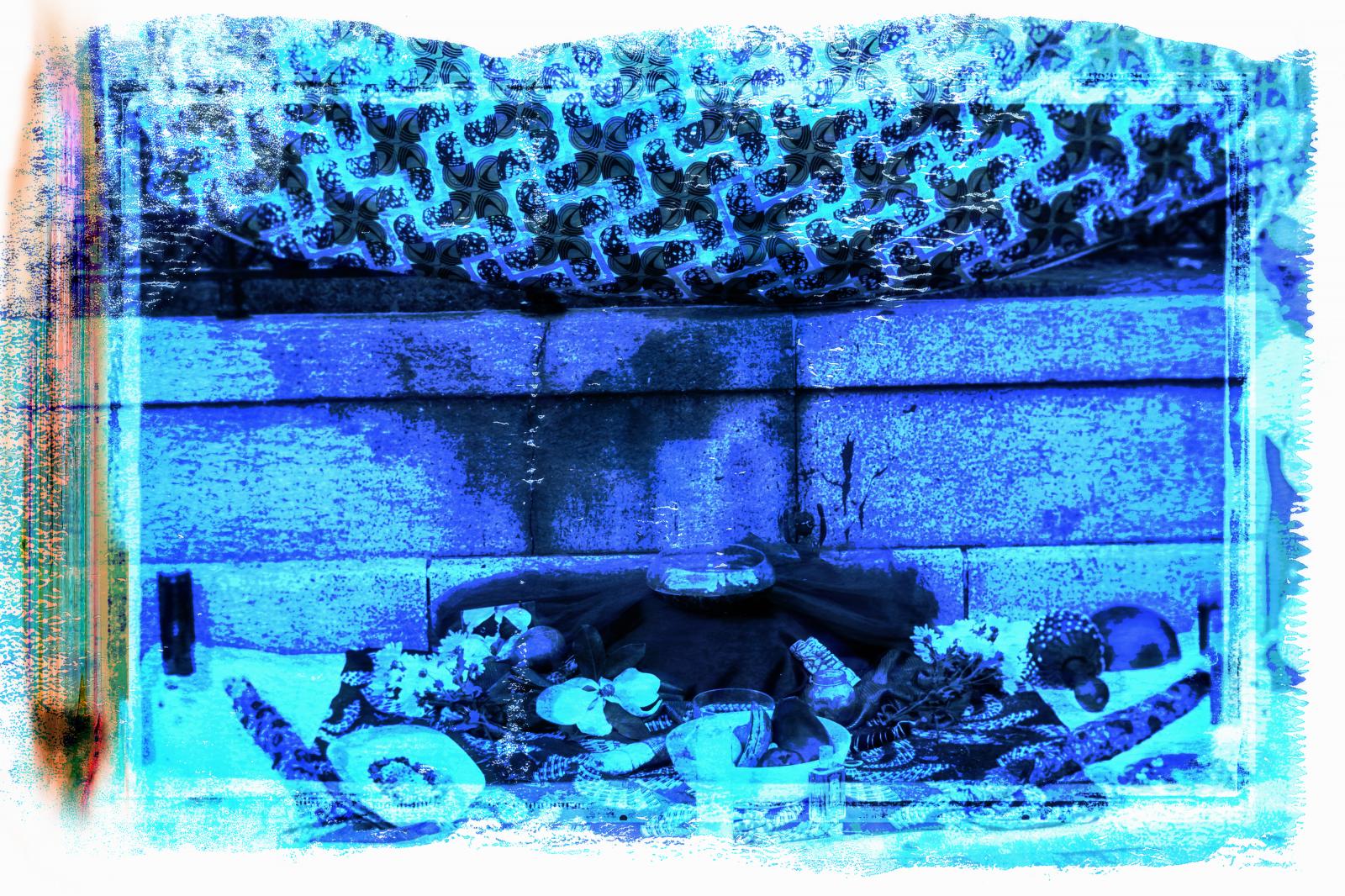

“Spirit Desire: The Vernacular of Freedom, and the Politics of Rescue in Queer Futures” my collaborator, Laura Wangari, and I contemplate the centrality of spiritual practice for queer people of African heritage. We spent three weeks with each other and with friends and fellow travelers, talking, chewing, drinking, laughing, dancing, cooking, and eating our way to understanding who we were, who we are, the contradictions in these spaces and times, and our spiritual selves. We see our many spiritual practices as acts of decolonization – ‘freedom narratives’.

As Laura Wangari comments“I believe my ancestral spirits leads me in many spiritual rituals and identification of spiritual healers. These kinds of rituals are very popular among the queer community on the coast because of the challenges we encounter in our relationships across board”. Spiritual practices offer us a way of healing and liberating ourselves from the tyranny of the heteronormative and the narrow identity politics of NGOs. The emergence of the queer donor programs [the NGOisation of QLGBTI activism] I believe, have distorted the unique queer life we once had along the Kenyan coast. Now we are encountering extreme, verbal and sexual harassment from other community members. This is one reason I love Kipini and Lamu as one can be more free in our sexual and gender expressions in these spaces. Now our spiritual practices help us to respond to the questions: How do we remain relevant in a family or community that despises you? How do your free yourself from a colonized mind?”

The two questions we kept returning to were how might we talk about queer spiritual practice and ways of being with stories that suggest a different narrative to that of the spectacular homophobia / homosexuality [see “Spectacular Homophobia” by Keguro Macharia & the “Queer African Reader”, Sokari Ekine & Hakima Abbas, Eds ]; and secondly how could we highlight the importance of healing and consciousness as truth telling amidst the narrative of the African as spectacular. Our conversations were an attempt to think of how to rescue ourselves from the ‘spectacular narrative’, that surrounds westerns notions of African homosexuality, homophobia, spiritual practices and the hyper “unAfrican, gay panic” rhetoric of various African religious and government bodies.

It is possible we don’t need to rescue ourselves or maybe the rescue is in performing our authentic selves in ways driven by both the everyday realities and by the presence of the ‘invisibles’ in those realities. In many ways, living a queer life is an undefined and unfixed reality which makes for a richness and depth beyond the narratives of ‘savior’ and ‘sinner’.“I was never advised on any order of conducting rituals and in this ceremony the purpose of the sea bath is a spiritual cleansing,” These spaces have spiritual habitats and I seek their permission to be present in their environment. I love the sea environment and I believe there are many spirits there and to connect with them is easier when I am clean totally clean. Nothing cleanses better than salty sea waters.

This knowledge was passed to me by my spiritual healer. I don’t know how I find myself dressed in white. Its the same color of my Islamic praying garment. ( The purity of the color gives me the belief that I’m talking to the good spirit, supporting spirit). In another ceremony which we can take place separately or before the bathing, I burn incense to appease the spirits. I was told spirits love sweet smells and I use various local herbs and salt. I seek permission to use the sea to bath to remove negative energies, to repel evil spirits and evil eyes causing any identified condition ( ie anger, confusion, hassad)” Laura Wangari

Size: h x w

Project Text

May/June 2017 I visited the coastal region of Kenya in a joint collaboration with Kenyan QLGBTI activist, Laura Wangari. Specifically, we visited, Mombasa, Malindi, Kipini, Lamu and Kilifi towns where we met with QLGBTI identified people. Our conversations over the three weeks centered on the many challenges faced by QLGBTI peoples and the spiritual practices they embraced as a way of negotiating the complexities and contradictions of living a queer life. From our conversations and travels along the coastal towns, we recognized that doing queerness looks different within Kenya, and within the intersectional realities of gender, class, economic access, religion, culture and moments in time. Artistically our intent is to show a shared love, and understanding, as we engage with the possibilities open to the non-normative black body. At the same time, it is important for us not to engage in a queer ‘mis-reading’ of what we witness, and assign western notions of identity in a search for the African Black queer body.

As a collaborative project, we speak only for those of us who are contributors. The 12 photographs of Laura Wangari, presented here, are part of “Spirit Desire: The Vernacular of Freedom, and the Politics of Rescue in Queer Futures” which we have named “Takassa: rescue our truths through cleansing & consciousness” The photographs were taken in June 2017 and made possible through a Global Arts Fund grant.African peoples have historically mediated life by speaking to the past as a way of moving through the present to the future. Here in our spiritual practices we speak with our spirits not as worshipers but as mutually dependent energies that we feel with our bodies but cannot see with our eyes; the visible to invisible and invisible to visible, an African Futurism guided by ancestors and traditional healing practices. To be here, to be past and to be future has required of us Black peoples, what poet Nicole Sealey, describes as an “hysterical strength” – not a “freak occurrence” but a persistence for and of survival. [ Hysterical Strength by Nicole Sealey]. In “Spirit Desire: The Vernacular of Freedom and the Politics of Rescue in Queer Futures” my collaborator, Laura Wangari, and I contemplate the centrality of spiritual practice for queer people of African heritage. We spent three weeks with each other and with friends and fellow travelers, talking, chewing, drinking, laughing, dancing, cooking, and eating our way to understanding who we were, who we are, the contradictions in these spaces and times, and our spiritual selves. We see our many spiritual practices as acts of decolonization – ‘freedom narratives’. As Laura Wangari comments.

“I believe my ancestral spirits lead me in many spiritual rituals and identification of spiritual healers. These kinds of rituals are very popular among the queer community on the coast because of the challenges we encounter in our relationships across the board”. Spiritual practices offer us a way of healing and liberating ourselves from the tyranny of the heteronormative and the narrow identity politics of NGOs. The emergence of the queer donor programs [the NGOisation of QLGBTI activism] I believe has distorted the unique queer life we once had along the Kenyan coast. Now we are encountering extreme, verbal and sexual harassment from other community members. This is one reason I love Kipini and Lamu as one can be more free in our sexual and gender expressions in these spaces. Now our spiritual practices help us to respond to the questions: How do we remain relevant in a family or community that despises you? How do you free yourself from a colonized mind?”

The two questions we kept returning to were how might we talk about queer spiritual practice and ways of being with stories that suggest a different narrative to that of the spectacular homophobia / homosexuality [see “Spectacular Homophobia” by Keguro Macharia & the “Queer African Reader”, Sokari Ekine & Hakima Abbas, Eds ]; and secondly how could we highlight the importance of healing and consciousness as truth-telling amidst the narrative of the African as spectacular. Our conversations were an attempt to think of how to rescue ourselves from the ‘spectacular narrative’, that surrounds westerns notions of African homosexuality, homophobia, spiritual practices and the hyper “unAfrican, gay panic” rhetoric of various African religious and government bodies. It is possible we don’t need to rescue ourselves or maybe the rescue is in performing our authentic selves in ways driven by both the everyday realities and by the presence of the ‘invisibles’ in those realities. In many ways, living a queer life is an undefined and unfixed reality which makes for a richness and depth beyond the narratives of ‘savior’ and ‘sinner’

“I was never advised on any order of conducting rituals and in this ceremony the purpose of the sea bath is a spiritual cleansing, These spaces have spiritual habitats and I seek their permission to be present in their environment. I love the sea environment and I believe there are many spirits there and to connect with them is easier when I am clean totally clean. Nothing cleanses better than salty sea waters. This knowledge was passed to me by my spiritual healer. I don’t know how I find myself dressed in white. Its the same color of my Islamic praying garment. ( The purity of the color gives me the belief that I’m talking to the good spirit, supporting spirit). In another ceremony which we can take place separately or before the bathing, I burn incense to appease the spirits. I was told spirits love sweet smells and I use various local herbs and salt. I seek permission to use the sea to bath to remove negative energies, to repel evil spirits and evil eyes causing any identified condition ( ie anger, confusion, hassad)”. Laura Wangari