Markets have always been central to city life. Human exchange in the form of goods, money, news and stories, has been widely recorded since ancient times.

In the early first century AD, two great civilizations emerged. To the West lay the Mediterranean world, unified under the Romans, and to the North lay Han China.

Together they developed an insatiable appetite for spices, aromatic woods, resins, perfumes, gold and later cloth.

As a consequence trading, hubs arose throughout the length and breadth of South and South East Asia.

Between the 16th and 20th century, the international demand for goods, primarily spices, led the Dutch, Portuguese, Chinese, Arabs, French and Indians to invest in maritime explorations and the establishment of colonies along major trading routes.

Such was the market demand, that spices and Indian textiles became a form of currency used by European governments and merchants in exchange for other goods.

The modern market places of Indochina are the product of centuries of trade.

Evidence of medieval trading hubs remains today in the form of food products, general goods and cultural traditions that echo those of 500 years ago.

The sale of spices and Indian textiles is still integral to today’s market life.

The global assault of malls and shopping centers has had some impact on the traditional markets of Indochina but in the cities and small towns of South East Asia, life still revolves around the market place.

Tourists are intrigued by displays of local culture and eagerly bargain for cheap products.

Locals continue time-honored traditions of not only shopping, but also eating and exchanging news and gossip, depending on the market place for social interaction.

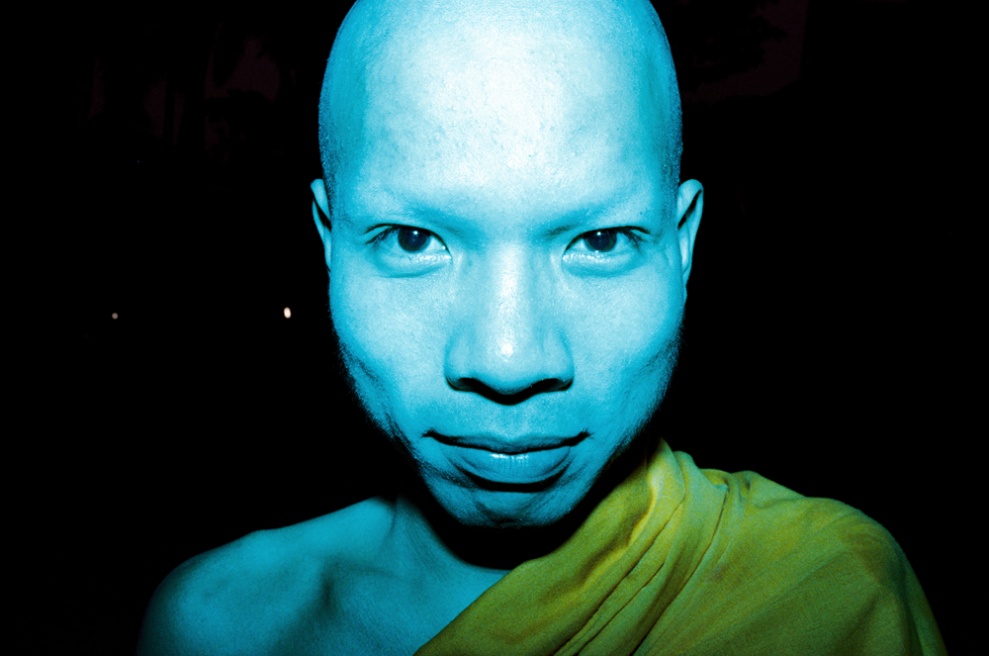

Trading can start as early as two o’clock in the morning and continue until after dark. Night markets begin in the afternoon and trade until the early hours. Most religious activities are conducted nearby and public transportation vehicles congregate there.

In the past, floating markets were commonplace on local waterways, where vendors traded from boats. They are now a dying phenomenon populated mainly by tourists.

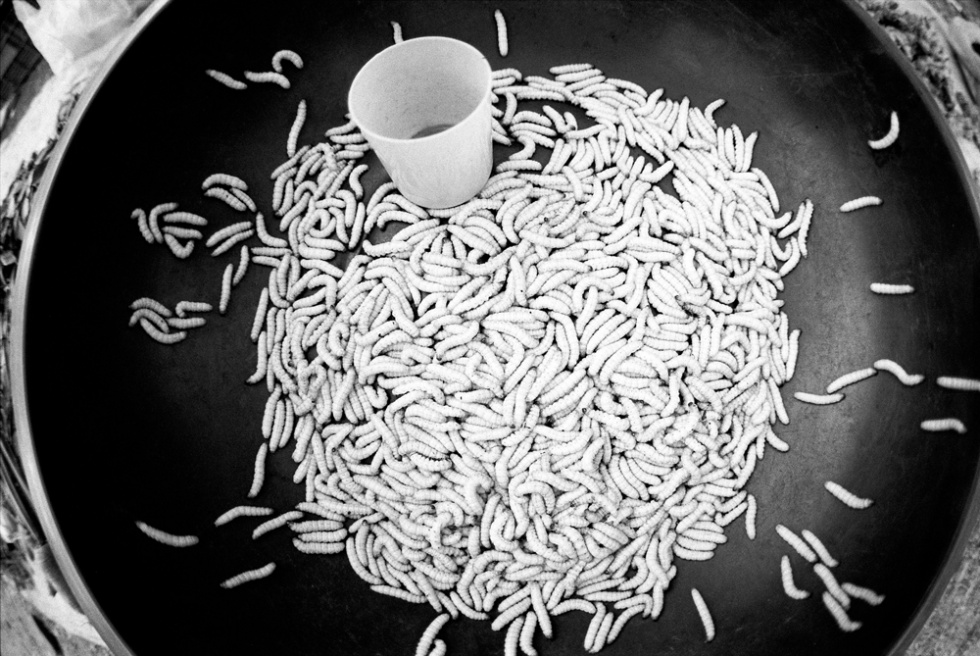

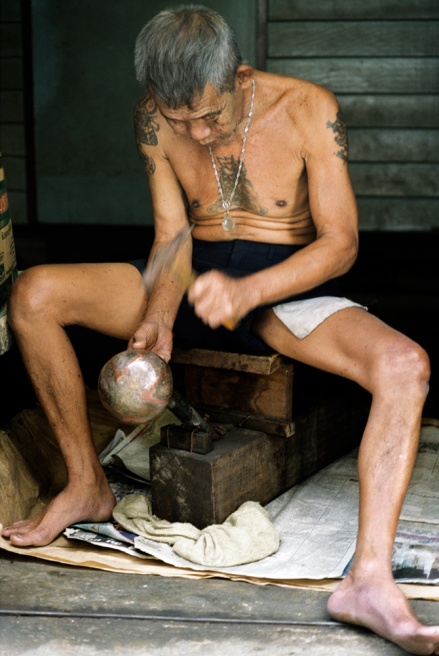

Vendors in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia display an enormous range of goods: fruit, vegetables, fresh meats and fish, flowers, silks, textiles, shoes, clothing, books, precious stones, antiques, handicrafts, cutlery and china, brassware, porcelains, wood carved products, snakes and wild animals, opium pipes. The variety is limitless.

In addition to the range of food, the range of people is astounding. Culturally diverse ethnic groups, such as the hill tribes, travel from neighboring areas to trade local, homegrown produce and handicrafts for electronic goods.

Traditionally, the market stalls are mostly run by families, including the very old and children. Their life styles are primitive and full of poverty’s attendant hardships.

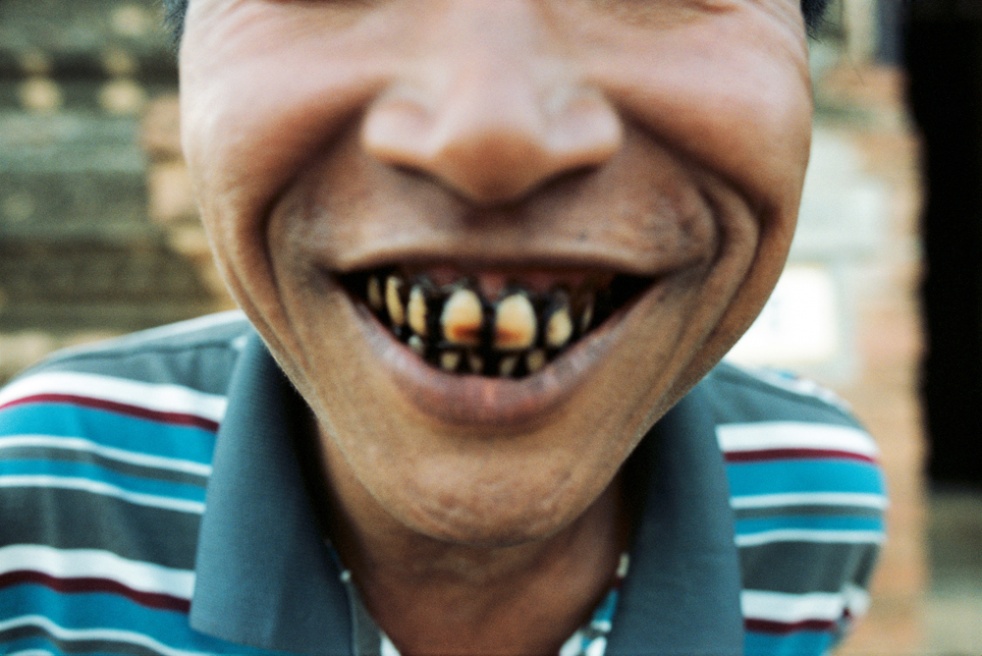

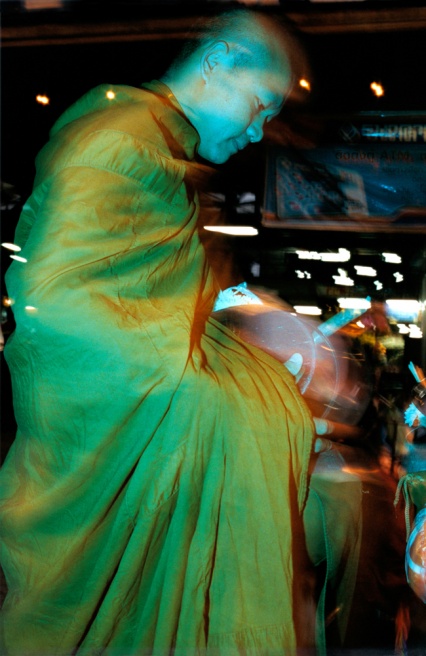

Remarkably, they are tranquil people, cheerful, helpful and charming, offering a rare personalized service to their customers, translating a Buddhist way of life of great tolerance and patience.

A walk through the markets of Bangkok, Hanoi, Yangoon, Vientiane and Phnom Penh can be visually overwhelming and physically challenging. It is easy to get lost in the narrow streets of Chinatown in Bangkok, and soon become unable to differentiate a food stall from someone’s kitchen.

The smells constantly push and pull, ranging from the scent of incense and flowers and the appetizing lure of barbequed meat to the stringent aromas of fresh spices and the stench of rotten garbage.

The frenetic and chaotic activities combined with the relentless noise become overpowering. One can feel remote and invisible in this setting, merely a witness to an ancient and unchanging drama.

One feels a sense of timelessness, a sense of history repeating itself.

The grin of a bare-footed and toothless old man, bearing a heavy load, the smile of a naked child leaning against a busy mother, the lumbering tread of an elephant pushing through a group of monks selecting items from a stall. These are vignettes that loop on themselves, continuously repeating throughout the centuries.

These elements of timelessness and repetition are inspiring.

A camera is a perfect medium for capturing vignettes: slices of life suspended in time.

The unchanging nature of these market places makes them unique to the modern eye. They are an anachronism in a modern world, representing enormous diversity combined with consistent predictability - an organized chaos.

Ivano Grasso © All Rights Reserved

www.ivanograsso.com