“Where is the most beautiful photo in the world?” the photography teacher asked me.

“In my pocket since six years ago,” I thought.

The only reason I did not say that answer out loud was that I wanted to keep the photo to myself. The teacher said: “It is in your mind and should remain there. The moment you let it out, you will be dead!” He meant artistic death.

Perhaps it was a good thing that I remained silent and did not hastily blurt out that silly answer. I did not want to seem dead to my teacher and friends that quickly. It was also good that the photo was somehow in my mind, and I always imagined it. But after I heard the teacher’s answer, I was afraid of printing it because I was not sure that another image would come to mind instead. That picture was the only boat that carried me to the past and reconnected me, sensually rather than metaphorically, with what was taken away from me. The picture from my father might have been all I wanted, but if I printed it, it would take a final form. The boat would then vanish from my mind, and I would lose my only means of travel to the past once again.

The teacher’s answer was not written on the page of a notebook the moment I read the question that summer in 2006 in Homs. Still, I remembered the whole story. The question was chiseled in my memory. I now think that I might have really been artistically dead when I worked in Damascus without realizing it. That pain only stemmed from my refusal to leave reality! I then wondered about the use of keeping that photo, which had an unknown gist and identity, so long as it did not save me anymore. I decided to print it that night.

The available technology did not facilitate my task of printing that ghostly photo. Even when I closed the projector lens all the way to the end and set the print time to a few seconds, I got a totally black image. I had to hold a black paper to block the light rays from the photosensitive printing paper and to move it back and forth as quickly as possible so that it would receive the right amount of light, just as the eye sees something in a flash. The result was worth the death of the most beautiful picture in the world—I could make out my childhood facial features as my father had captured them 20 years ago in that last picture where I stood in front of my older sister, who carried my youngest sister in her arms. However, shockingly and like in a fairytale, I woke up the next day, and on the floor was one picture that crushed 20 years of absence. I felt lighter. Although that image no longer inhabited my imagination, the pain and tiredness greatly diminished.

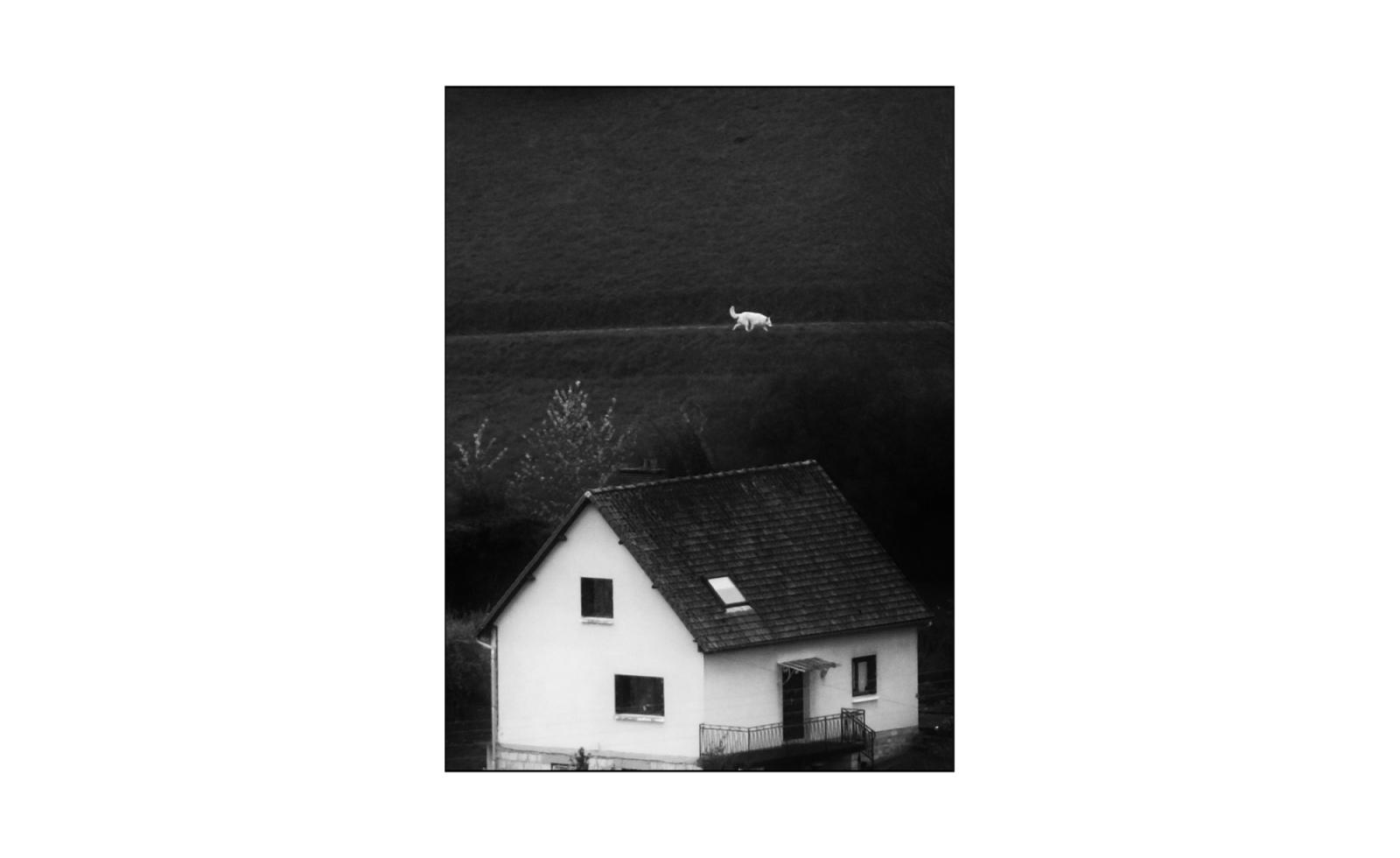

Searching for the reason, I thought that, although the imagined picture always seems a future one, which makes the photographer a theoretical human, imagination can only be based on past images, events, dreams, people and acquaintances that largely impose on the imagined picture the spirit of the past. The longer it lingers, the more it impedes the photographer from seeing reality. If that is indeed true, then the story of the five men wandering around the village and carrying a big boat over their heads actually applies to me. When a villager asked them why they were carrying the boat wherever they went, although it almost crushed them, they said, “This boat rescued us from death on the other bank of the river. We wouldn’t have survived without it, and we cannot leave it.”

Yet, how can one photo crush me? Perhaps it was not one photo. It was certainly the only physically present image, but maybe there were other ones concealed, lurking somewhere in my imagination. I got greedy. I wanted to be even lighter and perhaps grow a pair of wings! I began chasing the hidden images in my memory. To print them, I only had to summon them to my conscious mind and retrace their features accurately in my mind to stop them from endlessly shaping themselves in my imagination and draining me.