I can be me when you are here

“When I was a little boy, I used to ask my mom: "Mom, why am I like this? Why do I like men?, I don't like women. I came out of the closet when I was 15, there I found a friend named Kris." Says María Alejandra.

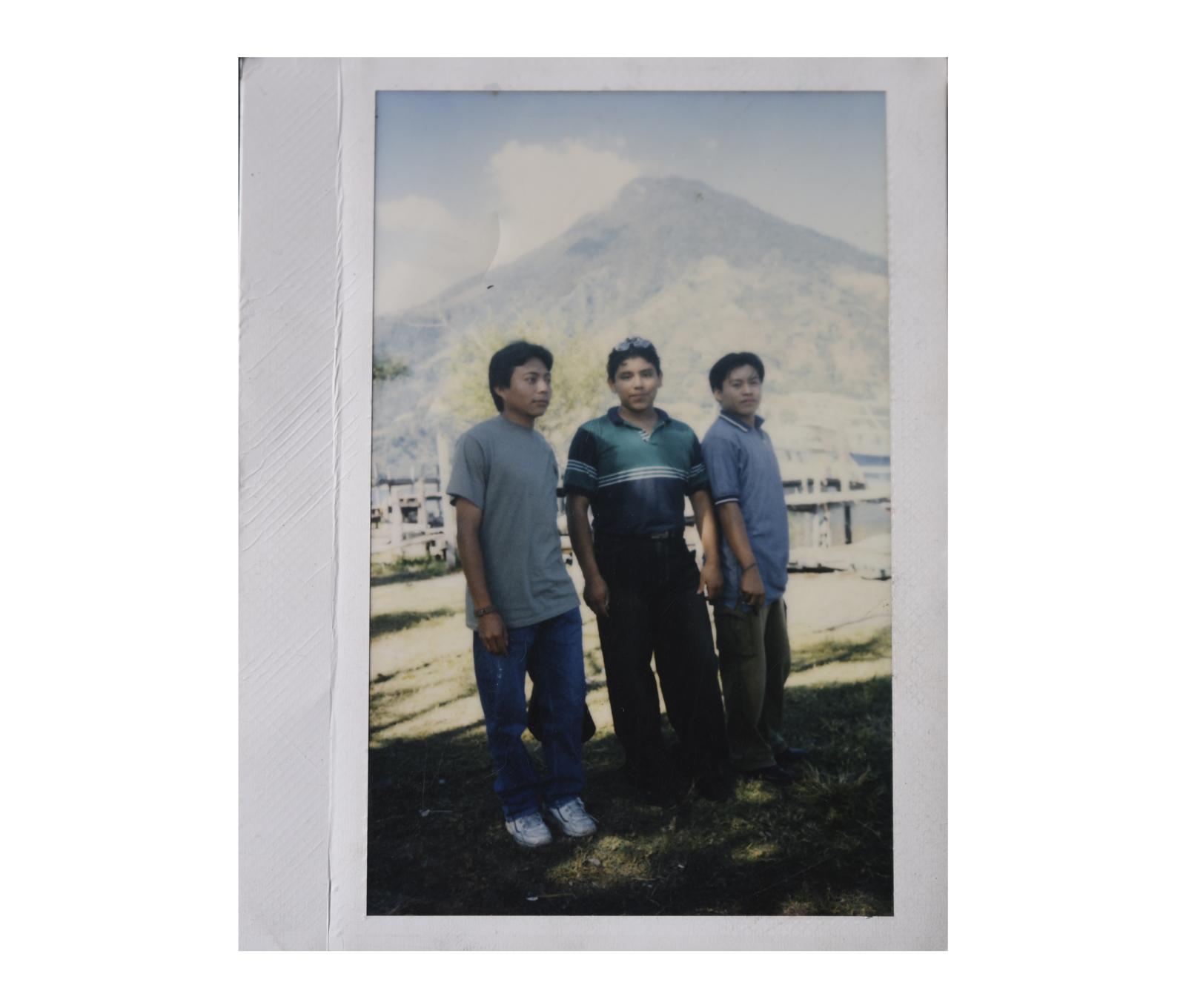

The story of Maria Alejandra "La China", and Kristel two indigenous trans women of Tz'utujil origin, has been forged by love, understanding and complicity. From a very young age they found in the community of Santiago, Atitlán, in Guatemala, where they began to discover their identity. Supporting each other they realized their preferences and similarities.

At one time Kris was locked up, chained and humiliated by her parents. During the four months she remained like this, there were many days when La China waited for her outside. I was waiting for the friend I used to play with as a kid playing dolls or to make tortillas in clay pots and sell them with beans and gravy, crushing bricks. Or the one who enjoyed a sunny day at the beach. But they refused to see her. Those chains, Kristel says, made her stronger.

Kris and China also found each other the compassion and affection that was taken from them when the people's men threw stones at them, mistreated them, exploited them at Christmas time, and shouted "crazy" at them any day on the street. However, together, they had discovered that they could be what they felt.

One of those days, while they were still little indigenous children walking through their village, China noticed a scar on her back and asked, Kristel told her that her dad had hit her with the wire of the radio because he didn't want him to play with homosexuals.

Indigenous Justice has two clear objectives: to get things back in place and to give back to the victim. In some towns, they try to keep homosexuals from being homosexual, and trans them to be men again. Sometimes, as a result, people are repressed to the point of marrying a woman and having children. The mandate is very strong, especially for those who fail to leave their communities.

In October 2019 in Guatemala, the observatory of violent deaths from sexual orientation and gender identity, recorded 15 murders of transgender women that year.

"I feel like a woman trapped in this man's body. I want to look pretty, I want to get attention. And not to hide what I am" says Kristel and with her inseparable friend China, they still face the obstacles of homophobia until their identity is recognized; be a trans indigenous woman.

Puedo ser yo cuando estás tú

“Cuando yo era pequeñito le preguntaba a mi mamá, ¿Mamá, por qué soy así?, ¿Por qué me gustan los hombres?, No me gustan las mujeres. Salí del closet cuando tenía 15, ahí me encontré a una amiga que se llama Kris.” dice María Alejandra.

La historia de María Alejandra, “La China”, y Kristel dos indígenas de origen Tz'utujil, se ha forjado a base de amor, entendimiento y complicidad. Desde muy pequeñas se encontraron en la comunidad de Santiago, Atitlán, en Guatemala, donde comenzaron a descubrir su identidad. Apoyadas una a la otra se dieron cuenta de sus preferencias, sus gustos y similitudes.

En una época Kris fue encerrada, encadenada y humillada por sus padres. Durante los cuatro meses que permaneció así fueron muchos los días en los que La China la esperaba afuera. Esperaba al amigo con el que jugaba de pequeño a las muñecas o a que hacían tortillas en ollas de barro y las vendían con frijoles y salsa, machacando ladrillos. O con el que disfrutaba de un día soleado en la playa. Pero le negaban verla. Esas cadenas, dice Kristel, la hicieron más fuerte.

Kris y La China también encontraron mutuamente la compasión y el cariño que les fue arrebatado cuando los hombres del pueblo les lanzaban piedras, las maltrataban, les explotaban cuetes en la época de navidad y les gritaban “locas” cualquier día en la calle. Sin embargo, juntas, habían descubierto que podían ser lo que ellas sentían.

Uno de esos tantos días, cuando aún eran pequeños niños indígenas caminando por su pueblo, La China le notó una cicatriz en la espalda y le preguntó, Kristel le contó que su papá le había pegado con el alambre del cordón de la radio porque no quería que se juntara con homosexuales.

La Justicia indígena tiene dos objetivos claros: que las cosas vuelvan a su lugar y retribuir a la víctima. En algunos pueblos, intentan que los homosexuales no sean homosexuales, y las trans vuelvan a ser hombres. Algunas veces, como resultado, las personas se reprimen hasta el punto de casarse con una mujer y tener hijos. El mandato es muy fuerte, sobre todo para quienes no logran salir de sus comunidades.

Hasta Octubre de 2019 en Guatemala, el observatorio de muertes violentas por orientación sexual e identidad de género, registraba 15 asesinatos a mujeres transgénero en ese año.

"Me siento una mujer atrapada en este cuerpo de hombre. Yo me quiero ver bonita, quiero llamar la atención y no ocultar lo que soy” dice Kristel y junto a su inseparable amiga La China, enfrentan, aún, los obstáculos de la homofobia hasta que su identidad sea reconocida; ser mujer indígena trans.