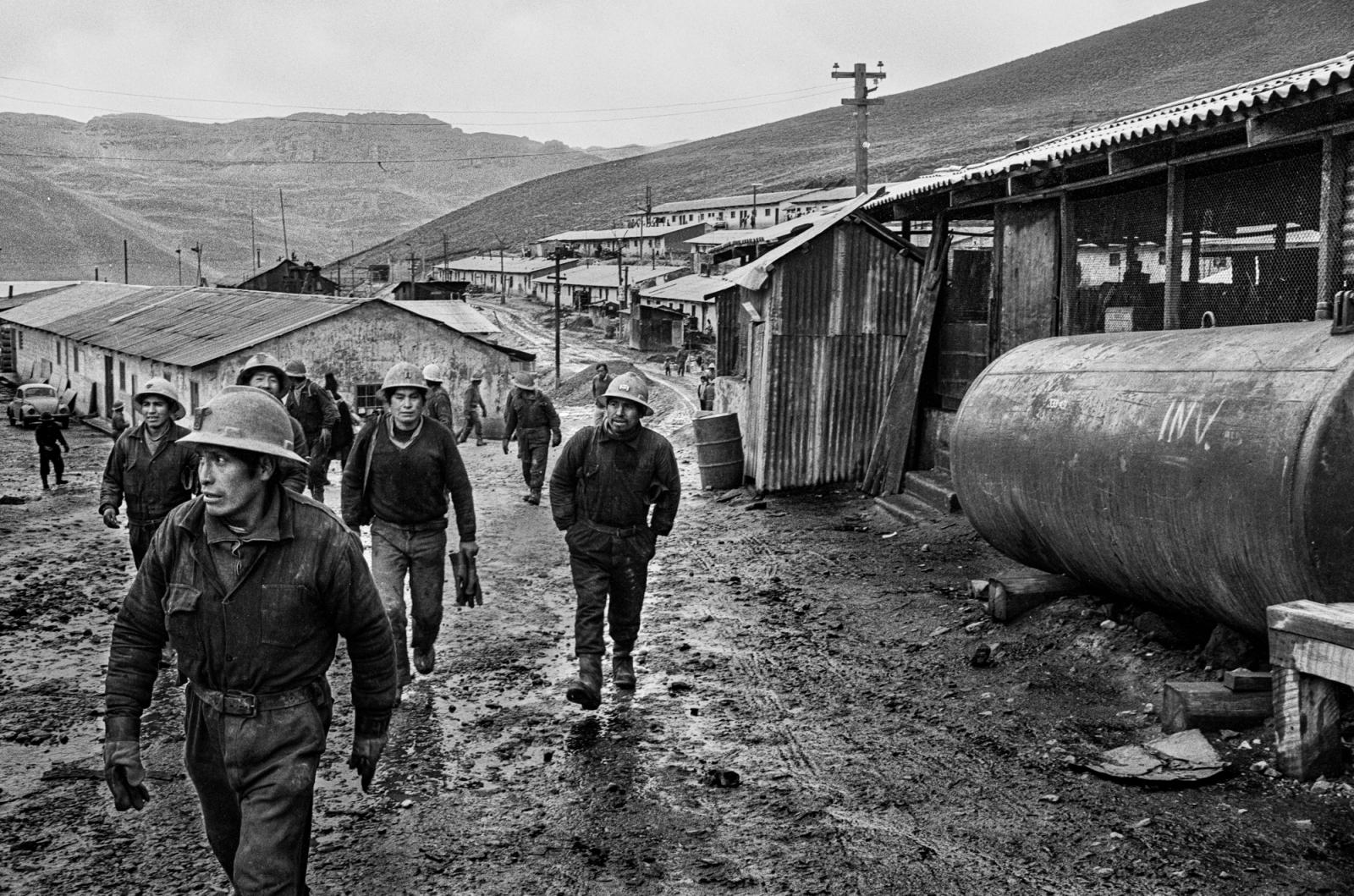

In Peru, in the barren stretches above the Andean timberline, there is a mining town named Morococha. In Quechua, the Indigenous language, it means "lake of many colors." At 15,000 feet, the air is scarce and breathing torturous. No greenery survives, not even the tenacious ichu, the wirelike bunch grass that can endure the gales of the high puna.

Morococha, soil of misfortune, beaten by hail and electrical storms, nevertheless held in its entrails the allure of mineral riches. In 1902, the Morgans, the Vanderbilts, and the Fricks formed the Cerro de Pasco Mining Company. An unlikely link was forged between Morococha and Wall Street, bringing enormous wealth to the Cerro de Pasco Corporation and utterly transforming the Peruvian highlands.

Attracted by the chimera of wages, the peasants began to leave their lands and their villages for the mines. They became miners with a daily work schedule, a shift, and sometimes, a union card. The former campesino learned to drink beer instead of chicha, to smoke cigarettes in place of chewing coca, to play soccer, to take pills, to use the words union meeting, asamblea, strike, work shift, winch, and Wall Street.

There are no monuments in Morococha, no Inca ruins, no cathedrals, only the mammoth machines that had been hauled across continents to transform a country. They are rusting now.

I came to Morococha to recover and research the work of an unknown Peruvian photographer, Sebastian Rodriguez, who had been the only photographer to document the life of the mines in South America beginning in 1928.