Public Project

Where the Walruses Sing

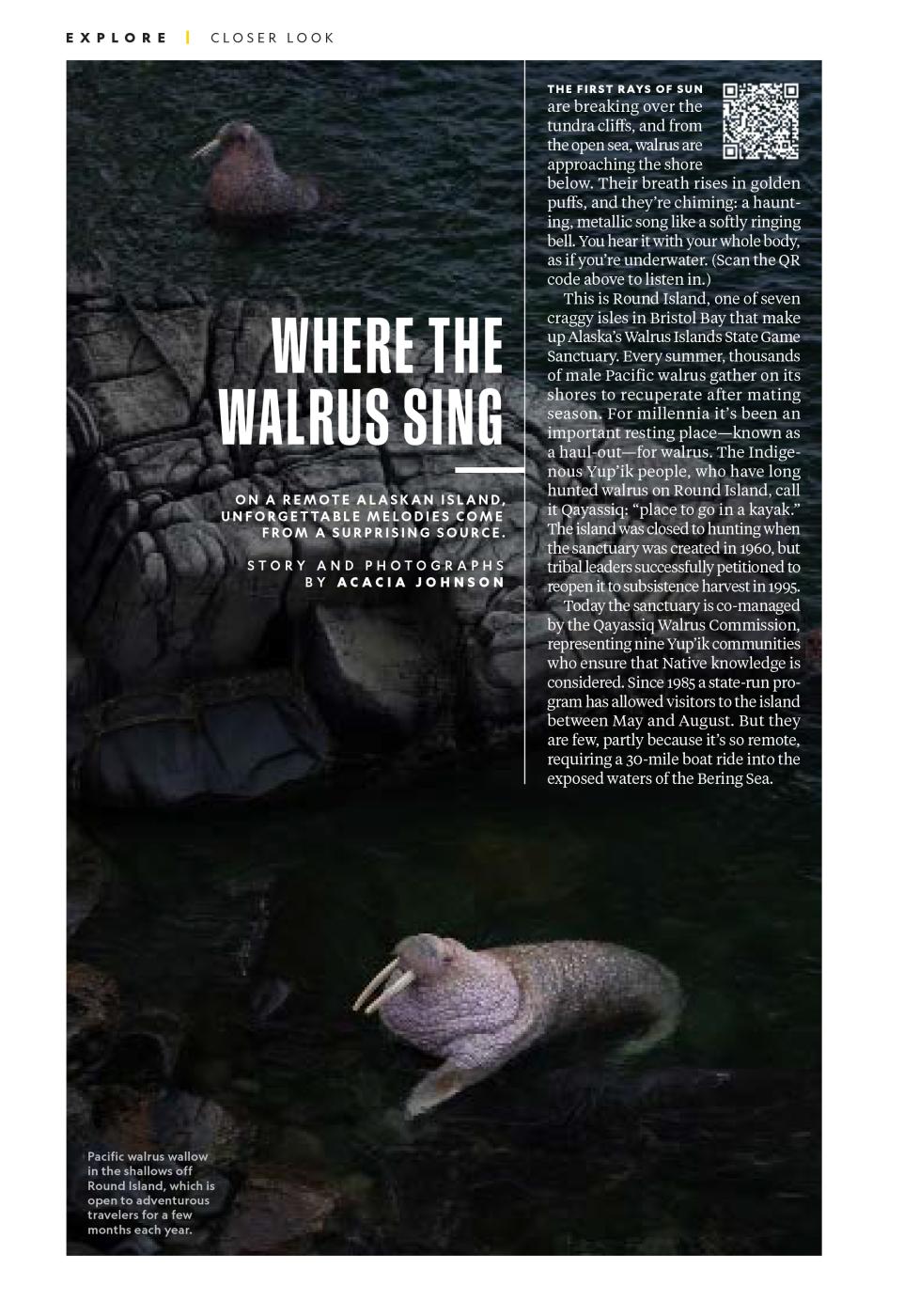

This is Round Island, one of seven craggy islands in Bristol Bay that make up Alaska’s Walrus Islands State Game Sanctuary. Every summer, thousands of male Pacific walrus gather on the shores of this small, verdant island to recuperate after mating season, while the females migrate north with the receding ice edge to give birth and raise their young.

Although melting sea ice is causing widespread changes in where walrus eat and rest, Round Island has been an important resting place for walrus—known as a haul-out—for millennia. Since 1985, a state-run visitor program has allowed travelers to visit the island between May and August each year, camping in the heart of walrus habitat.

I’ve come to Round Island with my brother, a wildlife biologist, to see walrus in the wild. Despite being Alaska’s longest-running wildlife-viewing program, the island is infrequently visited. That’s partly because it’s so remote. From the Yup’ik village of Togiak, Round Island is a 30-mile boat ride into the exposed waters of the Bering Sea. Calm weather is essential for the crossing: after Round Island, the next point of land is Russia, over a thousand miles away.

It isn’t easy to get to Round Island, but the adventure is part of the appeal.

A sanctuary for Indigenous traditions

The Indigenous Yup’ik people—who have hunted walrus here for over 5,700 years—call Round Island Qayassiq: “place to go in a kayak.” The island was closed to hunting when the sanctuary was established in 1960, but tribal leaders successfully petitioned to reopen it to subsistence harvest in 1995. Today, the sanctuary is co-managed by the Qayassiq Walrus Commission, representing nine Yupiaq communities who depend on walrus for subsistence, and who ensure that Indigenous traditional knowledge is considered. Every October, a limited hunt on Qayassiq allows these communities to continue the customs and deep ties to the environment that they’ve had since time immemorial.

An internship program through the Bristol Bay Native Association allows young people from nearby communities to spend time on the island and contribute to wildlife conservation. “Our traditional lifestyle is the most important thing to us,” says the organization’s Heidi Kritz.

When the Walrus Islands were established as Alaska’s first wildlife sanctuary, after decades of commercial walrus hunting, it was to protect what was then one of the last land-based haul-outs for Pacific walrus in North America. Despite weighing in at over a ton, with three-foot-long tusks and skin up to four inches thick, walrus are incredibly sensitive to disturbance. Boat traffic, loud voices, or the sound of aircraft overhead can cause them to stampede into the water, sometimes leading to injury or death for animals caught in the frenzy. If a site is disturbed frequently enough, the walrus will abandon it completely.

Thanks to the sanctuary’s protection, Round Island remains a seasonal home to thousands of Pacific walrus, as well as more than 250,000 nesting seabirds. As we approached by boat, after five days of waiting out stormy weather in Togiak, the island appeared almost enchanted: a steep dome of green rising from the sea, its summit shrouded in mist.

Arctic biodiversity

Margaret Archibald likes to track Round Island’s seasons by which wildflowers are in bloom. One of two Alaska Department of Fish and Game technicians who staff the island each summer, she greets our boat wearing black jeans and a sweatshirt, her auburn hair tousled under a baseball cap. In six seasons on the island, she’s studied its ecosystem so closely that she’s labeled wildflowers with tiny handmade signs. Cuckooflower. Arctic violet. Now, in July, the whorled lousewort blooms: a magenta, orchid-like flower curling up delicately along the walking trails where we first step ashore. “I apologize in advance if I’m a chatterbox,” Archibald says. “You two are the first visitors we’ve had in weeks.”

When our boat arrives, the landing beach is packed with sleeping walrus. To avoid disturbing them, we unload onto a nearby boulder face, keeping our voices low. As Archibald helps us carry our gear to the campground, the air buzzes with the chirps of savannah sparrows and hermit thrushes. Green tundra grasslands, thick with wildflowers, stretch along the island’s cliffy shore; surprisingly lush for being, technically, part of the Arctic tundra biome.

After pitching our tent, we join Archibald on her daily rounds. It’s her job to maintain the island’s trail system, to oversee the visitor program, and to enforce the three-mile zone that protects the island from boat traffic and commercial fishing.

She considers her most important task to be the daily wildlife counts of walrus, seabirds, and an endangered population of Steller sea lions. Bristol Bay’s fisheries make it a vital ecosystem for Alaska’s economy, and data collected about Round Island’s seabirds and marine mammals—which function as climate indicator species—is some of the region’s most consistent. As Arctic temperatures rise, she explains, what happens on Round Island provides valuable insight into what’s going on in the broader marine ecosystem.

Archibald leads us along a well-maintained trail through clifftop grasslands, pointing out good viewpoints for nesting puffins and parakeet auklets. The island’s red foxes, she says, have just given birth to kits. Then we arrive at a viewpoint for First Beach—a grassy ledge, blooming with lupine—and peer over the edge. Hundreds of walrus are piled pink onto the rocks a mere hundred feet below us. You can smell them: salty, marine, and fecund. We sit down in the grass to keep a quiet, low profile, so they’re at peace with our presence.

Camping in walrus habitat

Round Island is ideal for experienced campers accustomed to bad weather. With eight wooden tent platforms overlooking the sea, a composting outhouse, and a large cooking tent with a picnic table and a propane stove, it has more infrastructure than any other walrus viewing area in Alaska. One of the things that attracted me to the adventure of Round Island was its packing list, which requires a stormproof tent capable of withstanding 60-m.p.h. winds; a tent-pole repair kit; and enough food for an extra week’s stay. Campers must be prepared for rapidly changing weather. Out here, nature is in charge.

Some nights, the wind blows so fiercely that it sounds as if our tent will be ripped from its platform. Other nights, it is so quiet that I can hear the walrus when I’m inside the tent: breathing, roaring, whistling, their ethereal chiming produced by air being pushed between chambers in their pharyngeal pouches. Most mornings, when I leave the tent, the wind blows in a marine mist casting the grasslands in silver, increasing the sense of a myth or a dream.

Walrus watching

Walrus are social, gregarious, and thigmotactic animals—meaning that they prefer to be in close contact with each other, tusks and all. (Orphaned baby walrus, in captivity, require constant physical contact to survive). Piled by the hundreds to rest on Round Island’s beaches, they jostle frequently for position, groaning and poking each other with their tusks when annoyed.

When they’re out at sea, they’re eating benthic invertebrates such as clams: an average of a hundred pounds of them a day, unearthed from the ocean floor with their sensitive whiskers called vibrissae, and consumed by suction, leaving the shells behind.

For hours each day, my brother and I wander between the island’s numerous overlooks, watching the walrus. They’re graceful swimmers, almost dancerly, when they approach the beaches from the sea; so pale pink from immersion in the cold water that they appear almost white. Then they lumber ashore, all blubber and tusks, using their foreflippers to haul their jiggling bodies across the smooth, dark rocks. As they join the hundreds of others piled onshore, their skin will turn a dusky, rosy pink as blood flows to their extremities to cool them down.

“Walrus have evolved to be this unique, amazing, specialized clam-eater,” Archibald laughs as we chat on her cabin deck one afternoon. She explains they are a keystone species, helping to shape the entire biotic community they live in. When they forage on the sea floor, they churn up vast quantities of nutrient-rich sediment, providing food for smaller organisms up to seabirds, large fish, seals, and even polar bears further north. But despite their vital role in the ecosystem, they often fall low on the priority list for conservation.

Walrus are hard to track, and existing data has been deemed insufficient to classify them as endangered. In 2014, Round Island lost all its state general funding, despite needing relatively few resources. Today, its program has continued thanks to grants and donors, including a live walrus webcam on Explore.org.

Archibald says that experiencing walrus in person is one of the best things that can happen for their conservation. “Once people come here and see them, they’re going to forever be more aware of walrus habitat—and the fact that walrus are real animals,” she says. “They’re not a sticker or an emoji.”

The walrus we see are beautiful, complex, individual animals. I learn to estimate their age via their skin, which forms into thick, textured nodules called “bosses” as the animal grows older. Some of their tusks are striated or broken off into ivory stumps. Despite their size, they’re shy, and easily spooked if one of us humans moves too quickly. When they greet each other in the water, they gently touch whiskered snouts.

Talking to Archibald makes me see walrus with fresh eyes. She tells the story of a tiny, lost walrus calf being cared for by the older males, even hitching a piggyback ride; or aging walrus being tended to by younger ones. Watching them—their different colors, their battle scars, their antics—reminds me that all animals are individuals, with personalities, emotions, and empathy.

A conservation relationship

On our last morning on the island, the sky clears after days of mist. I get up in the nautical twilight to climb the steep Traverse Trail along sloping tundra cliffs to a craggy peninsula where seabirds nest. When I look back at camp from high on the hillside, under the light of a lone, fat star, the blue-hued grassland below ripples with the foundations of ancient homes. I think of what Kritz told me: that spending time on these traditional lands as an intern was a healing experience. I wonder if people who walked Qayassiq thousands of years ago were similarly awestruck.

It’s high tide when the sun breaks over the horizon, but even the thin strip of exposed beach below is piled high with walrus glinting amber in the light. More wallow offshore, chiming softly as they wait for space to join the crowd. Thousands of seabirds cycle above; a fox runs by, dripping with morning dew, a crush of black feathers in its mouth. I think of how easy it is, in a place like this, to understand how everything is connected.

It’s not easy to get to Round Island. Committing to the journey helps the walrus and the people who depend on them. It keeps the place staffed and protected. Walrus may not be an endangered species yet, but they are worthy of attention and conservation. As the climate changes and walrus across the Arctic are forced to forego their ice floes for more land-based haul-outs, the structure of the marine ecosystem itself may be changing. Walrus may turn out to be a more important part of the picture than we think.

National Geographic, 2021

10,743