Public Project

Connections to Kith and Kin

“I just found this last night,” he says, shaking his head. “That’s heavy, heavy stuff.” Mr. Delorme’s parents had always told him he’d had a twin – but as the death certificate proves, it wasn’t a twin at all. His older brother had died, and Marvin had inherited his name.

Mr. Delorme was born in Muskeg River, Alta., to a band of Métis with Cree roots. Around 1968, his family was forced to settle in Grand Cache and, like so many Indigenous people of his generation, he was taken away to a residential school. So for much of his life, he knew almost nothing about his family. But a program at the Vancouver Public Library’s Britannia branch – located in the heart of the city’s most concentrated Indigenous population – is helping people like Mr. Delorme reconnect with their heritage.

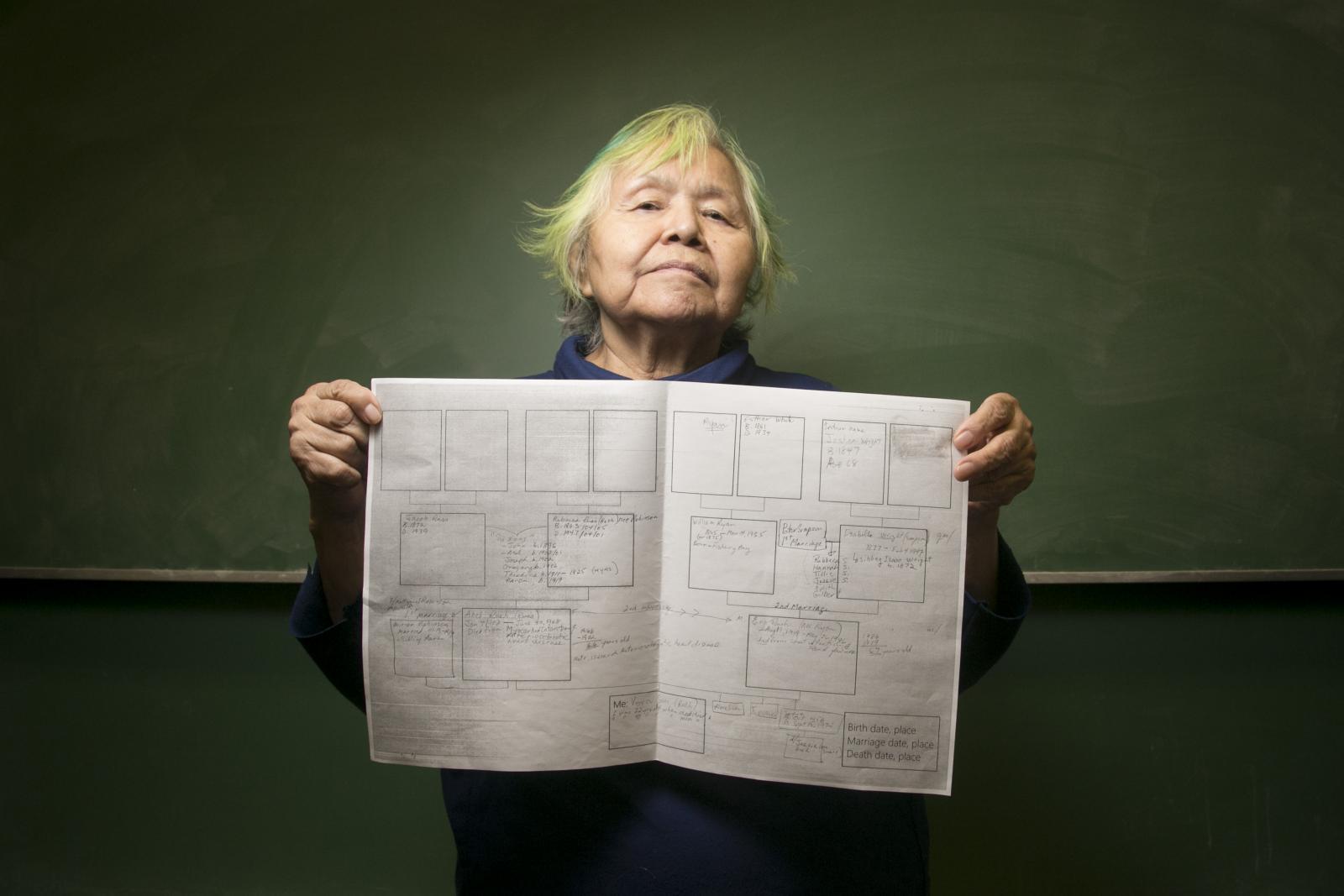

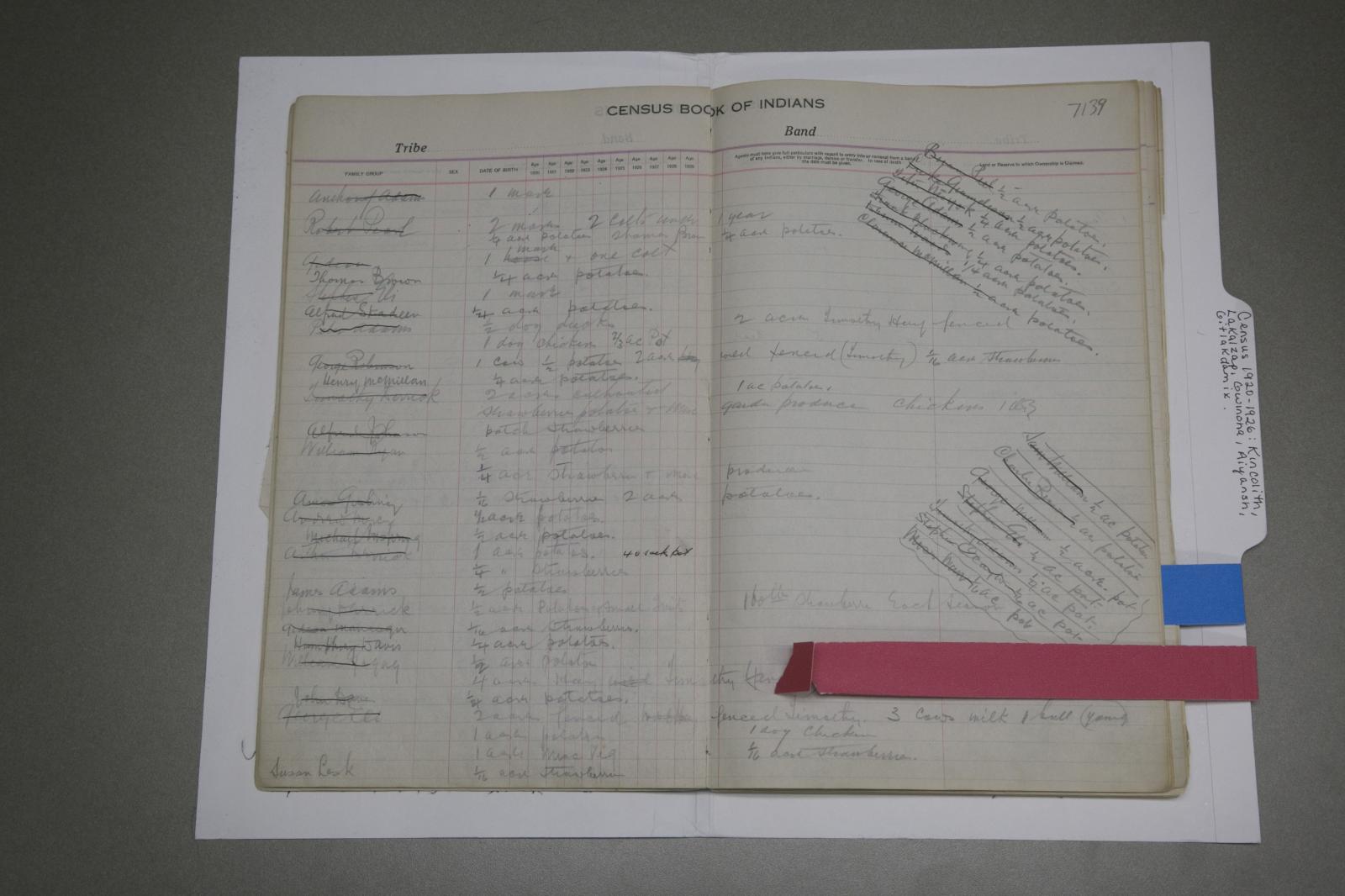

The Connections to Kith and Kin program pairs skilled archivists with community members to help comb the often-overlooked mountain of Indigenous records maintained by Library and Archives Canada. These records are often more extensive and invasive than those kept on non-Indigenous Canadians, but the documents offer Mr. Delorme and others an opportunity to collect the broken links of their lineage and piece them back together.

Bureaucrats diligently documented births, deaths, baptisms, trap-line permits and even grocery bills of Indigenous people around the country. The LAC collection is vast, comprising, according to brochures, “250 linear kilometres of government and private textual records,” along with thousands of hours of audio recordings, millions of books and five billion megabytes of digital files.

Buried in all that data was the death certificate of Mr. Delorme’s namesake.

Before he was taken away, Mr. Delorme remembers being somewhat nomadic, moving from place to place hunting and trapping with his family. But residential school broke him down over time, he says, and broke down his connection to his heritage, as well. Once he was old enough, he discovered big cities such as Edmonton and Calgary. “I never went back,” he says. Instead, he drifted from one city to the next, working construction and carpentry jobs until, inevitably, “I’d get in a fight, and that was it – I’d be gone.”

For 20 years, he struggled with addiction before getting sober in 2002 and training as a counsellor. He now works in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, not far from the Britannia branch.

As Mr. Delorme grew roots in Vancouver, his mind started to wander back to his childhood. He yearned for home and family. When he heard about the Kith and Kin program, he jumped at the opportunity to try to retrace his steps back to Muskeg River. As he peeled back layers of paperwork, he was surprised to find that his family was still there. For the first time in decades, he phoned home. Would anyone pick up, and would they remember him?

The answer, as it turned out, was yes.

Read the rest in The Globe and Mail

2,835