Public Project

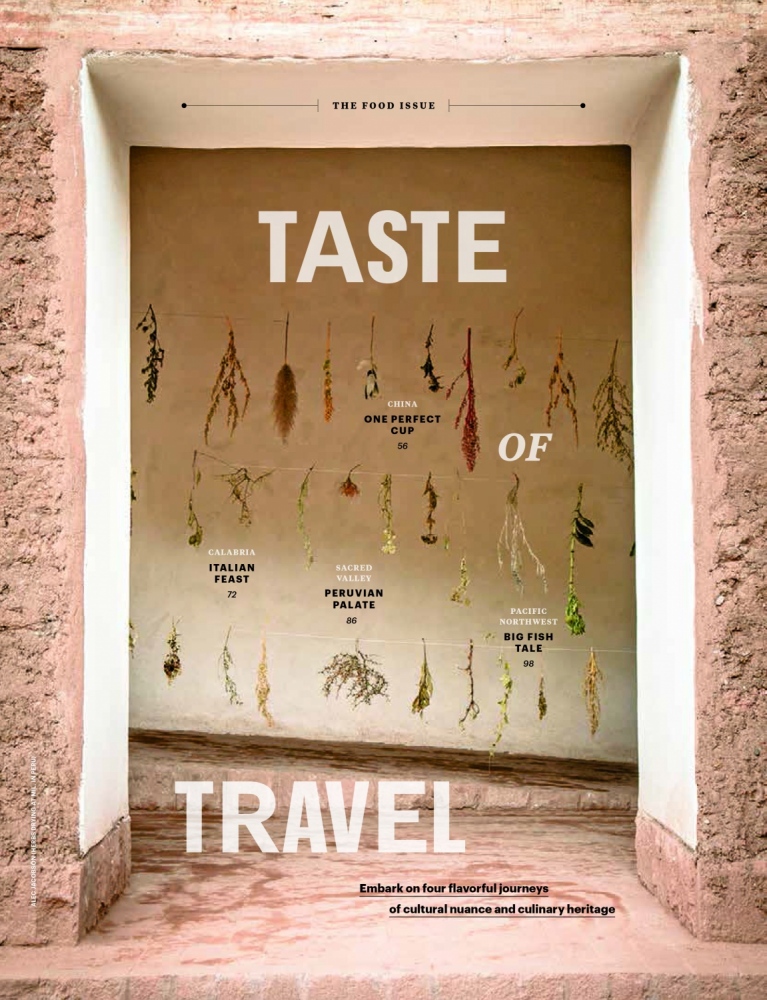

National Geographic Travler: Peruvian Palate

With support from the National Geographic Society

In the northeast corner of Cusco Cathedral, tucked behind the altar, past gilded alcoves

and towering columns, Jesus and his disciples feast on guinea pig.

Marcos Zapata, a Cusco native, painted the scene in 1753. The Spanish had conquered his

people and razed the Inca palace of Kiswarkancha, building the cathedral on the ancient foundation. But, with a massive oil painting, Zapata brought the heritage of his people back to the table.

Walking out of the cathedral into the historic heart of Cusco, I briefly felt the pull of the past. The Inca name for the city translates as “navel” or “center.” Their 11,150-foot-high capital, ringed by the tall peaks of the Andes, has been continuously inhabited for some 3,000 years. But the past faded as a set of signs around the edge of the colonial Plaza de Armas—KFC, McDonald’s, Starbucks—brought me jarringly back to the present. Generations of travelers have come to Peru’s Sacred Valley, which stretches from Cusco northwest to Machu Picchu, to see the intricate stonework the Inca left behind. In their wake fast-food joints and restaurants catering to a Western palate have sprung up. Peruvian farmers have taken to planting white spuds instead of the heirloom potatoes in a rainbow of colors that their ancestors cultivated.

Fried chicken and fries may be delicious but so is guinea pig. This was one of the main things I learned from my first trip to Peru in2018 when I’d stayed in a Quechua village a few hours’ drive and a short hike from Cusco, working on a National Geographic Society–sponsored project to study shifting trends in indigenous Andean food with National Geographic Explorer Rebecca Wolff. Everything I ate in each dirt-floored Quechua kitchen was memorable, from fire-seared duck to heirloom potatoes roasted in a sod huatia oven to simple barley soups spiced with ají chiles. Now I was back in the Sacred Valley to get a fuller taste of the Inca’s living culinary heritage—which Zapata knew could not be vanquished.

3,633