Public Project

New York Times: Genetic Engineering In the Mosquito War

Summary

Working on a remote island, scientists think they can use genetic engineering to block a malaria-carrying species of mosquito from spreading the disease — and do it in just a few months. But governments are wary.

I reported this story for the New York Times with the global health reporter Stephanie Nolen from the country of São Tomé and Príncipe in the Gulf of Guinea.

Words by Stephanie Nolen:

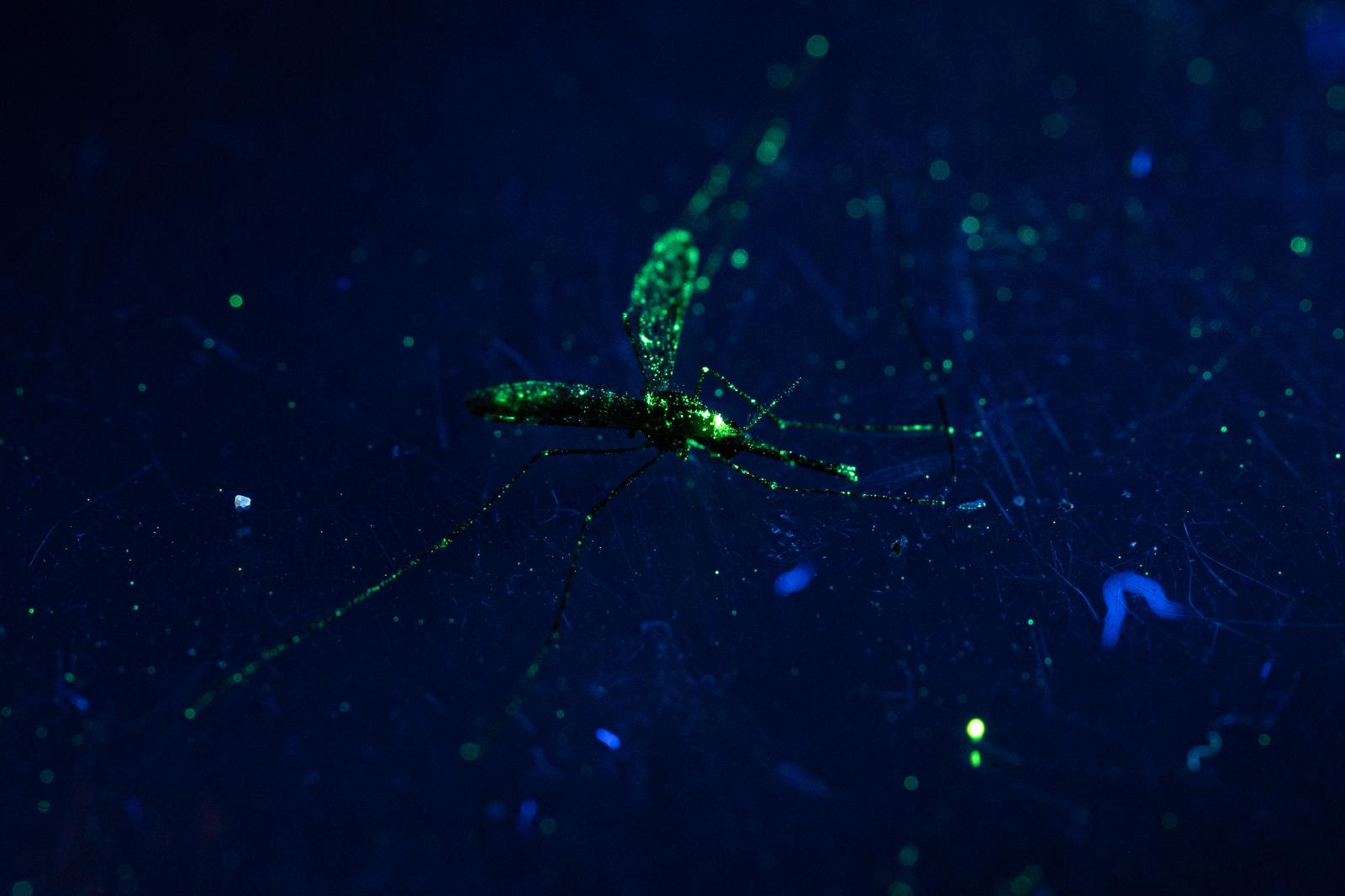

On a muggy evening in July on the island of Príncipe, part of a volcanic archipelago 200 miles off the West African mainland, 11,000 mosquitoes dusted in fluorescent green powder flew together into the heavy equatorial air, tiny volunteers in the service of science.

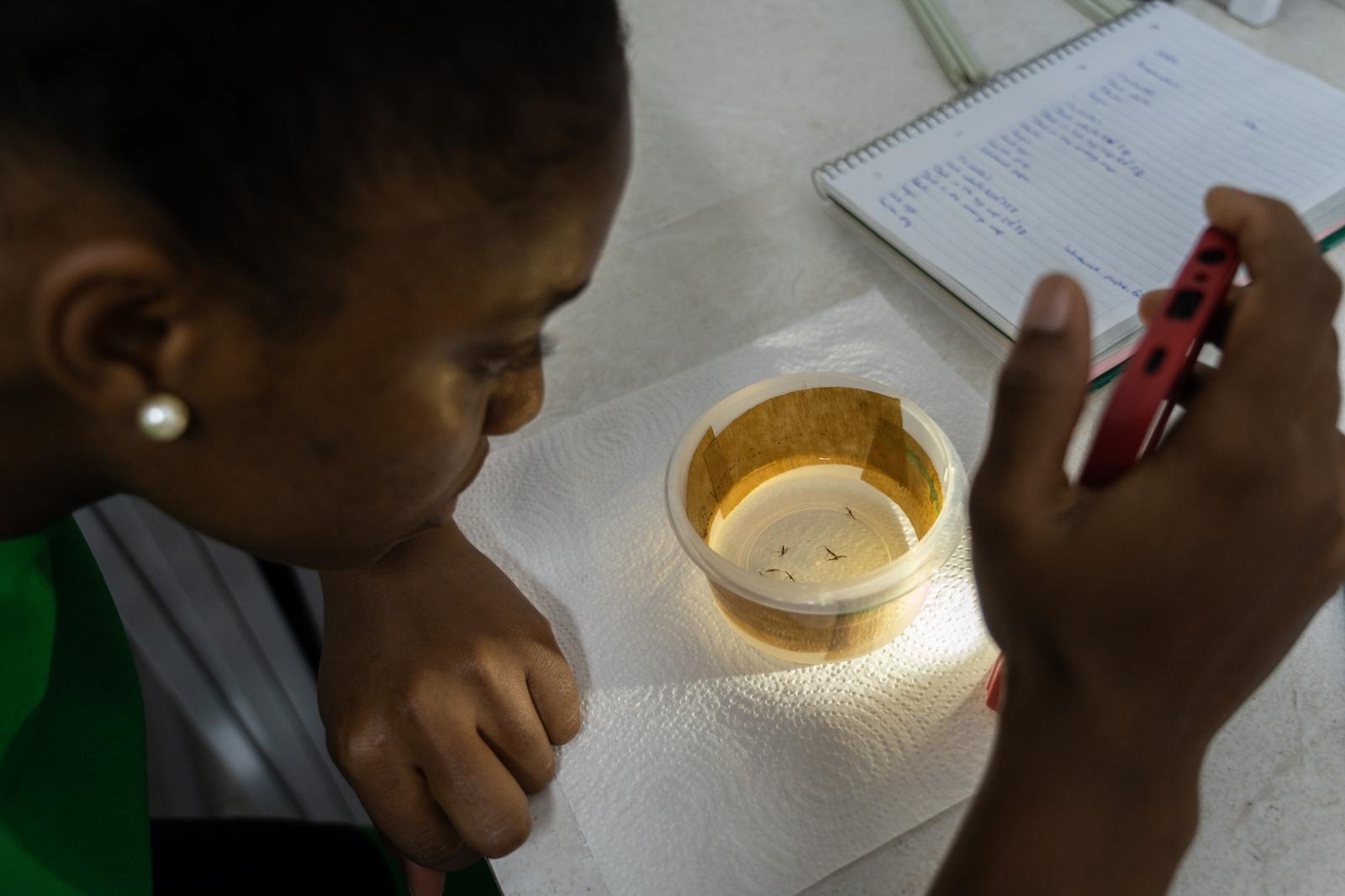

Over the next 10 nights, another group of volunteers, human ones, sat outside their houses in villages nestled in the rainforest, keeping their arms and legs exposed in the damp dark, waiting for the faint tickle of a mosquito in search of blood. Once one alighted, they switched on a headlamp and used a rubber tube attached to a glass vial to suck the insect up and seal it in a cup.

The mosquitoes were raised from larvae, dusted green, then set free, by an international team of scientists who are trying to bring cutting-edge genetic science to an ancient fight — that against malaria, the most deadly mosquito-borne disease.

For each of the 10 mornings after the mosquito release, the scientists fanned out along the northeastern coast of this remote island, collecting cups humming with mosquitoes. They then took the insects to a makeshift lab in their hotel suite in the island’s one town, Santo Antonio, where they slid them under the light of a fluorescent microscope. Twelve of the 253 mosquitoes that had been caught glimmered with tiny particles of the green powder that clung to their scaly bodies.The recaptured green mosquitoes offered insight into how far they flew and the size of the mosquito population, clues to the dynamics of malaria in this country. And they moved the scientists one step closer to their goal: replacing the mosquitoes that live here now with ones they have genetically modified so that they can no longer transmit the malaria parasite.

Their idea is to release a small colony of genetically modified mosquitoes, just the way they did with the green-dusted ones, to mate with wild ones. The gene engineering technology they are using could, in just a few generations — a matter of months when it comes to mosquitoes — make every member of the species that transmits malaria here, the Anopheles coluzzii, effectively immune to the parasite.

This team, working with a project called the University of California Malaria Initiative, has already successfully engineered the Anopheles coluzzii to block the parasite in a lab. And the scientists believe they can harness gene drive, a process in which an inherited trait spreads swiftly throughout a population so that all the species’s offspring will carry it, not just half, which is the way inheritance normally works.

The malaria situation in São Tomé and Príncipe, an African island nation with a population of 200,000, epitomizes the current challenge in the global struggle against the disease. The country is among the world’s least developed, and it has depended on foreign aid to fight malaria. Various campaigns over the past 50 years drove cases down, only to have them resurge worse than ever when the benefactor moved on.

Over the past 18 years, with nearly $21 million from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, São Tomé has used a package of tools — including insecticide-treated bed nets; new and better drugs; killing larvae in bodies of water; and indoor spraying of homes — to stunning effect. No one has died of malaria here in the past five years...

Read the full story on the New York Times page

The Gamble: Can Genetically Modified Mosquitoes End Disease?

The Gamble: Can Genetically Modified Mosquitoes End Disease?Working on a remote island, scientists think they can use genetic engineering to block a malaria-carrying species of mosquito from spreading the disease — and do it in just a few months. But governments are wary.

Nytimes.com

10,178