Public Project

Jocotenango, A Village of Indians

In 2017 we decided to move to Spain, the need arose to document the Jocotenango neighborhood of Guatemala City, where I was born, as well as my grandmother, my father, my sister and, now, my daughter Clara.

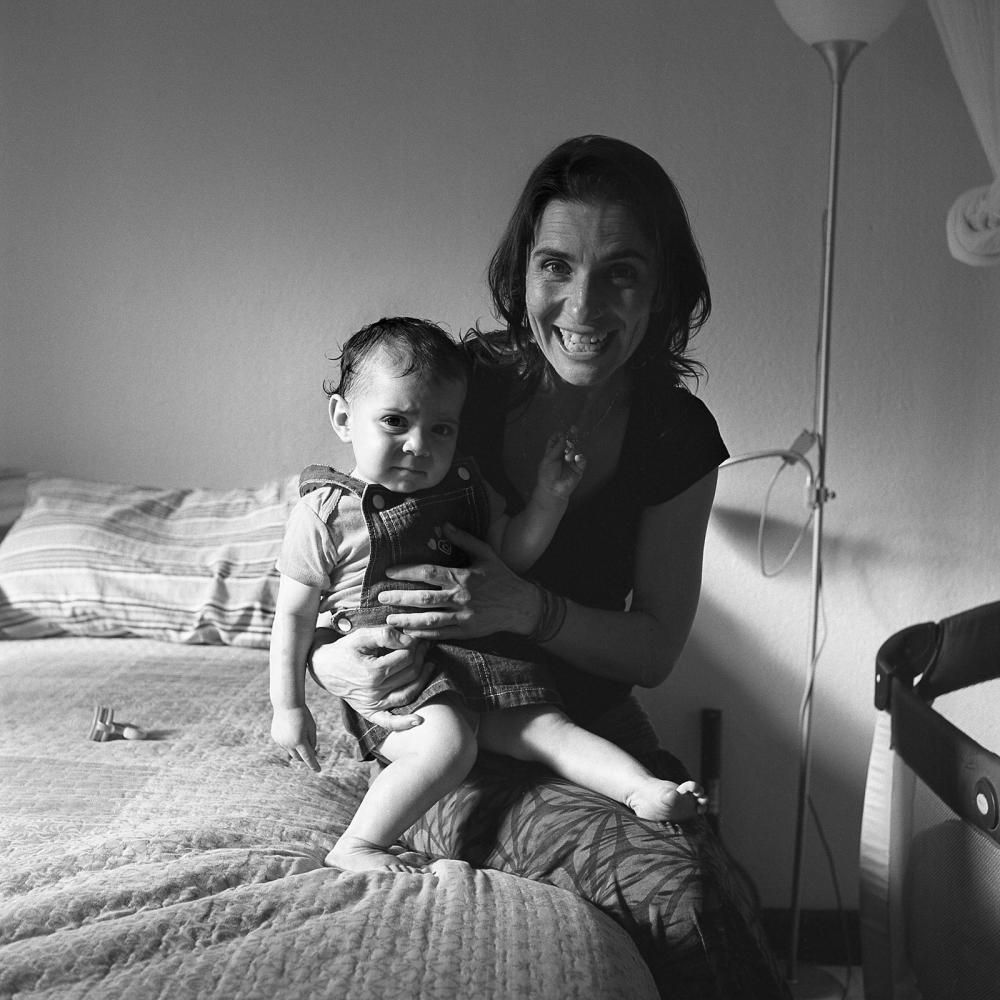

During the first 14 months of Clara's life I dedicated myself to photographing the space and the people who live and wander in the barely three square kilometers that delimit this neighborhood, so close but so different from the city center. Celia, Carlos, Hilda, "El Chaparro" are some of the neighbors who came to this place.

I set out to try to understand what it was that made us all meet in its streets, parks and corners. What I found was the story of “a town of Indians”, the forgotten story of those who built Guatemala City: indigenous Cakchiqueles forced to leave in the 18th century of the original Jocotenango, near La Antigua Guatemala, and condemned to live segregated in the Assumption of Jocotenango, a town that they founded from scratch and that was close to the New City of Guatemala, today the capital of the country.

It was January 27, 1779 and it was “more than 1,900 indigenous Cakchiqueles, men, women and children with name and surname” who began to cover the labor required by the new city. Around 1800 - the new capital that was intended to move its inhabitants away from the destruction of its volcanoes for the third time - the small town already had “one hundred and forty-five thatched houses, a church as well as the parish house, a jail, a central park and a cemetery. ”

A century after its foundation, the life and history of this town of Indians ends. In 1879, President Justo Rufino Barrios, under a governmental decree, indicates that "the municipality of Jocotenango is abolished and is annexed as a canton to the city of Guatemala." The liberal era is consolidated and after the rupture with the Catholic Church, the Indians of the town see the church, the streets and the cemetery they built collapse.

Before their eyes the people they built became extinct, and never again became their territory. The new constructions arrived, a Parisian-style promenade called Avenida Simeón Cañas, a racecourse, a bullring, new neighbors, ladinos, Creoles, foreigners. Very few indigenous people managed to resist the new way of life.

No one of the founders' last names is heard in the neighborhood anymore, only a few of its streets remain, its great fair on August 15 in honor of its patron saint the Virgin of the Assumption and the park where I learned to ride a bicycle and my daughter took her first steps.

To portray for Clara those who were our neighbors, remember them and rescue them in their daily places is the mission of this project, which in my new stage of migrant acquires a special poetic and documentary sense.

1,437