Public Project

In an Italian wine region, question marks over quarantine

Summary

Italy’s Piedmont is dependent on eastern European migrant workers to harvest its grapes, so much so that some fear coronavirus quarantine requirements have been flouted

This article was published on October 14, 2020 by balkaninsight.com (part of BIRN, Balkan Investigative Reporting Network: a network of non-governmental organizations promoting freedom of speech, human rights and democratic values in Southern and Eastern Europe)

Photos by Luca Prestia, text by Cecilia Ferrara

When, over the summer, Italy introduced travel restrictions on eastern Europeans, Boban Pesov quickly called on his workers to return from vacation in their native North Macedonia. As manager of the agricultural cooperative his father founded in Piedmont, Italy’s famed northwestern wine region, Pesov could see trouble ahead. «We rented a building where they could go through the quarantine, each with his or her own bathroom, and helped them make declarations to the Sanitary Authority», Pesov told BIRN. «And we tested them». «We have done everything in the safest way», he said, but added: «I have the impression we were one of only a few to do so». Desperate to avoid a repeat of the spring, when COVID-19 tore through northern Italy, Italian authorities imposed quarantine requirements on arrivals from parts of eastern Europe, including fellow European Union members Bulgaria and Romania, which alongside North Macedonia are the source of tens of thousands of seasonal workers who descend on Italy every year to harvest the grapes that go into some of the most prized sparkling wines in the world. Since early August, citizens of North Macedonia are forbidden from crossing the border unless they hold EU passports. Coupled with the 15-day quarantine for Bulgarians and Romanians, the measures have disrupted a wine industry worth more than a billion euros to Piedmont and threatened the pay packets of impoverished eastern European agricultural labourers. Some appear to have flouted the rules, as evident in the significant gap between the number of seasonal workers who registered on arrival and the actual number required for the harvest and seen working in the vineyards. «These are not realistic numbers», said Pesov, an architect and cartoonist by trade but who manages the 12-year-old Arco del Lavoratore cooperative in Roddino. «We have not grasped the risk of an outbreak, now that food and wine tourism is just coming back to life».

Lucrative industry reliant on outside labour

The wine industry is the backbone of the Piedmont economy. According to the region’s Institute for Economic and Social Research, IRES, the production process is worth more than 920 million euros per year, while exports bring in another 365 million euros. Then there’s the booming agritourism and wine tourism sector, particularly around the fine wine territories of Langhe, Monferrato and Roero that account for such illustrious names as Barbera d’Asti, Barolo, Dolcetto d’Alba, Barbaresco, Moscato, and Alta Langa. But for decades, the industry has been reliant on migrant workers from eastern Europe and, increasingly, from Africa, many of whom face exploitation. Fabrizio Garbarino of Via Campesina, a rural association that fights for the rights of farmers, said eastern European workers were «everywhere» in the 1990s and 2000s. «Bulgarians slept in cars, Macedonians camped by the river», he said. In the town of Canelli, where Italians first produced sparkling wine in 1865, Garbarino described how hundreds would congregate on Piazza dell’Unione europea [European Union Square] at 6 a.m. and wait to be collected by a cooperative ‘gang-master’ who paid them four euros an hour. «The entrepreneur is happy because at the end of the job, the cooperatives issue an invoice to the worker and, even if the wages are too low, he certainly won’t be the one to protest», said Garbarino. In 2015, «La Stampa» journalist Riccardo Coletti reported on the practice, which he dubbed ‘The Canelli System’. «It was a well-known system that was tolerated», he said, but authorities «are much more careful» today. This harvest season, sanitary authorities responsible for the towns of Alba and Bra told BIRN in mid-September that 98 workers had registered with authorities as per the coronavirus restrictions. Yet in the Barolo area, which lies between these towns, there were at least 300-400 in the vineyards, according to Monforte d’Alba mayor Livio Genesio. Of the 98 registered, 68 worked for Pesov’s Arco del Lavoratore. Sanitary authorities in Asti said 54 people from Bulgaria, 261 from Romania and 61 from North Macedonia had registered since 1 August, far below the number required to handle the harvest on time. In Canelli, a Macedonian who works with a cooperative and has lived in the town for 20 years, said a number of Macedonian seasonal workers told him no one had checked where they had travelled from. «Many on the buses coming over have asked us why they have to stay at home for 15 days, while others were working in the vineyard the day after they arrived», said the man, who declined to give his name. In early September, in the centre of Canelli, there were five parked buses marked as travelling between Italy and eastern Europe, including the towns of Delčevo and Kočani in the mountainous east of North Macedonia, as well as a number of vehicles with Bulgarian licence plates. Nearby, a small, grey-haired Bulgarian man said he hadn’t missed a harvest in Piedmont for the past 10 years. Asked if he had quarantined, the man, who appeared to have slept in the open, replied: «No. I took the test before leaving. I’m okay». Pesov, himself originally from North Macedonia, said he knew the rules would be broken. «On August 10, I wrote a letter to the Ministry of Agriculture predicting exactly what has happened and what is happening», he said.

Local authorities slow to act

More than 5.000 citizens of North Macedonia live in Piedmont, the majority of them working in viticulture. At

harvest time, friends, relatives and other seasonal workers descend on the areas of Canelli and Albese, knowing they can earn in one month what it takes them four months to earn at home. «With winemakers ageing and foreign investments increasing, small companies with three or four hectares have disappeared», said Claudio Solito, owner of the La Viranda winery in the heart of Langa Astigiana. «Now you need at least 20 hectares to survive. And you can no longer manage the harvest with family and neighbours. Macedonians are needed. And the cooperatives». Roberto Caponi, director of labour and welfare at the agricultural federation Confagricoltura, said that across Italy, some 180.000 people are employed at the peak of the harvest. «Forty per cent are foreigners: among them, 80.000 come from both EU and non-EU countries. Romanians, for example, are 13 percent of the total», he said. In August, Confagricoltura and Coldiretti CIA, another agricultural federation, sounded the alarm over the threat to this year’s harvest from the lack of seasonal workers. Caponi said he had floated several ideas to address the problem, including the use of ‘active quarantine’, by which a worker would continue to pick grapes while technically living in isolation. The autonomous northern province of Trentino is the only region in Italy to introduce such a measure so far. Local authorities appear to have been slow to take up the issue. Only on August 24, a week after the harvest had begun, did local mayors meet the agricultural cooperatives and wine producers. «Yes, it was a bit late», said Monforte d’Alba mayor Livio Genesio, who hosted the meeting, «but we didn’t know if the decrees would change or not». He said the numbers of workers arriving from COVID hotspots was «limited». «Many who used to come have not returned»

Changing profile

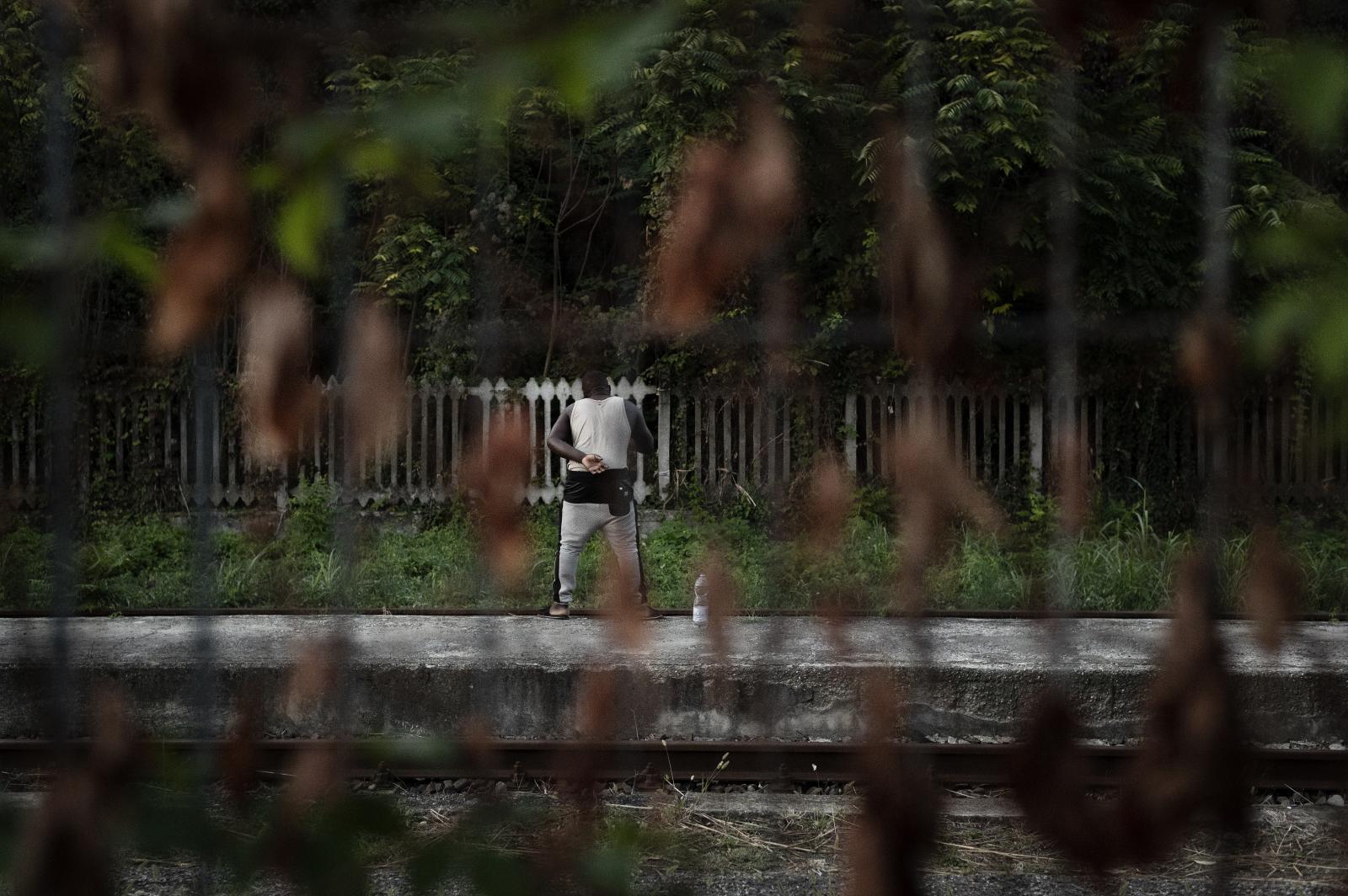

In Canelli, a town of 10.000 inhabitants, almost 10 per cent of the population is of Macedonian origin. Piergustavo Barbero, known as Bimbo and the patron of Pusbein, one of the oldest agricultural cooperatives in the Cannellese area, has worked with Macedonians for 30 years. They first arrived illegally, but Barbero said he helped them get out from the grey economy into legitimate employment. Exploitation by «dirty» cooperatives remains common, he said. «If they hire them, they pay them for two or three days even if they work 50 days», he said. Pusbein, in contrast, pays its workers «for at least 160 days a year» so they can count on a pension. Two cooperatives in the region run by Albanians were shut down in May following investigations by the Italian Carabinieri and Guardia di Finanza. Now, the profile of those finding work in the region is changing. «The Macedonians are retiring at a rate of about ten a year and their children no longer want to stay in the vineyard, but want to build machines for viticulture», said Barbero. «Others go to Germany and Switzerland, where they are paid better and there are welfare payments for families». They are slowly being replaced by migrants from countries such as Senegal, Nigeria and Mali, who, like those who came before them, crowd Canelli’s Piazza dell’Unione europea. «Gang-masters keep them sleeping in hovels without any hygiene, paying them three euros per hour and insulting them all the time», said Lieutenant Colonel Piero Breda, commander of the local Carabinieri. «Whoever tries to rebel risks being sent away and not being paid». Africans can be seen sleeping in a disused railway station in Canelli, camped under a parking lot or on the banks of the Belbo river where some Bulgarians have also set up their temporary home. «It is absurd that it is not possible to find a housing solution for them», said Claudio Riccabone, head of the local branch of the Caritas Catholic charity. Over recent years, Caritas has organised beds and hot meals for the seasonal workers flocking to Canelli. But centre-right mayor Paolo Lanzavecchia, elected last year with the support of the far-right Lega party, blocked an increase in the number of free beds for this year’s harvest, arguing it would give African migrants an «unfair» advantage by allowing them to charge less than other workers. Riccabone said the move was short-sighted, given the circumstances. «Wouldn’t it be better to keep them in a place where there is a doctor and where their fever is measured every day, considering the current health emergency?».

This story was financed by the European Journalist Centre as part of the IJ4EU fund for cross-border investigative projects

2,725